Kabuliwallas of Kolkata: Memory, Nostalgia and Performance in the Life of a Community

Moska Najib and Nazes Afroz’s photographic project From Kabul to Kolkata: Of Belonging, Memories and Identity focuses on the evolving life of a community of travelling merchants in exile—the Kabuliwallas of Kolkata. As travelling salesmen of dried fruits, condiments and other assorted products; their position has been cemented in the Bengali imagination through a short story by Rabindranath Tagore, titled Kabuliwalla. This has painted them as romantic, semi-exotic travellers from a distant frontier-land that is perhaps less identifiable with the political history of the country called Afghanistan and more with the imaginary, nostalgic home of “Pashtunistan.” As Najib says in an interview: “Many also believe that they come from the land of Pashtuns—Pashtunistan—and when you remind them that geographically it does not exist, many respond and say, ‘Well, yes. It does.’ Their existence is very layered in reality and the perception of what their identity is.” Since many of these members of the Pashtun community have lived in Kolkata for several generations, their association with their Pashtun homeland is the proper object of their nostalgic identity—it works as a firm cultural anchor for their life abroad, while sealing off any real possibility of return.

Members of the community gather at the famous Maidan of Kolkata—located close to the colonial Fort William grounds—to perform some of their favourite social rituals like kite flying, anda kushti (hard boiled egg-fights) and the Pashtun Attan dance (which is a folkloric performance, continuing since pre-Islamic times).

Najib says about this photograph: “A Kabuliwalla, Sultan Khan, showed us this stunning dress that he had managed to keep which belonged to his mother... He was so proud because it was the only memory of Afghanistan which he carried with him all these years. For me, this photograph is very prominent because you never see a Pashtun man holding something so feminine. And that contrast of nostalgia and of belonging is very poignant and eye-opening in this photograph.”

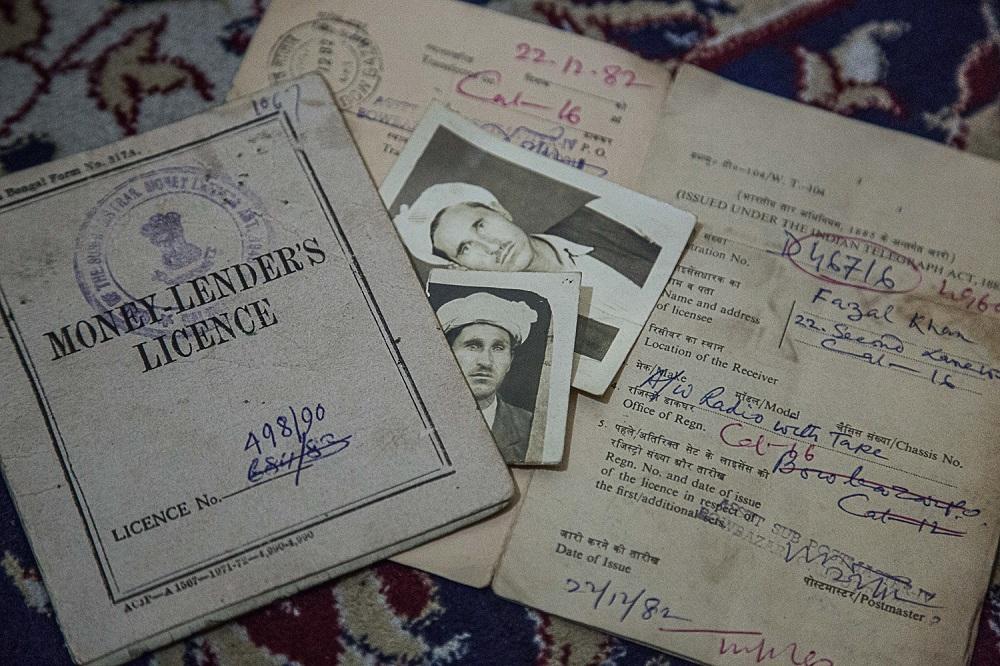

Like any other ethnographic documentary project, this travelling exhibition—research for which started as early as 2012—seeks to visibilise not only the members of this community but the patterns of their social life in the city. In this effort, however, women turned out to be a casualty. Najib highlights the difficulty she faced in accessing the women of the community and photographing them for their project for reasons of respectability. It suggests a hesitation on behalf of the community towards the nature of the public sphere in Kolkata, or India at large, over which they have no control. Many of the men photographed by Afroz and Najib hold up several identity cards but no passports, reflecting an ambivalence and anxiety over citizenship rights. In the absence of positive, affirmative narratives of their identity in the world (as Afghans they are associated with violence and tribalism), the community is forced to court a certain form of insularity to protect their sense of cohesion.

As the community is increasingly pushed into ghettoes with their personal rights suspended in uncertainty, their crowded living spaces bear the stress of multiple functions, purposes and uses. In spite of it, the use of posters and images confer it with a more coherent narrative of nostalgia and aspiration.

It is ironic—and tragic—that the form of insularity assumes the same shape as Bengali responses to the colonial public sphere, when a private sphere at home was consecrated as the spiritual, feminine sphere of authentic nationality against the “materialistic” public sphere of colonial authority. From Tagore’s originary moment of myth-making and romance to the modern, traumatic histories of displacement and exile—the Afghan communities of Kolkata may have changed in the eyes of Indians over time. However, they have seldom spoken directly—as they do through these photographs—about the material and spiritual world of their habits and locations. This exhibition offered an opportunity to listen closely to those—largely male—voices.

Many of the ‘Kabuliwallas’ of Kolkata struggle to get themselves recognized by the government, in the form of ID and ration cards. As a result, they are exempted from the normative claims of citizenship in the country.

All images by Nazes Afroz and Moska Najib.