The Quotable Gesture

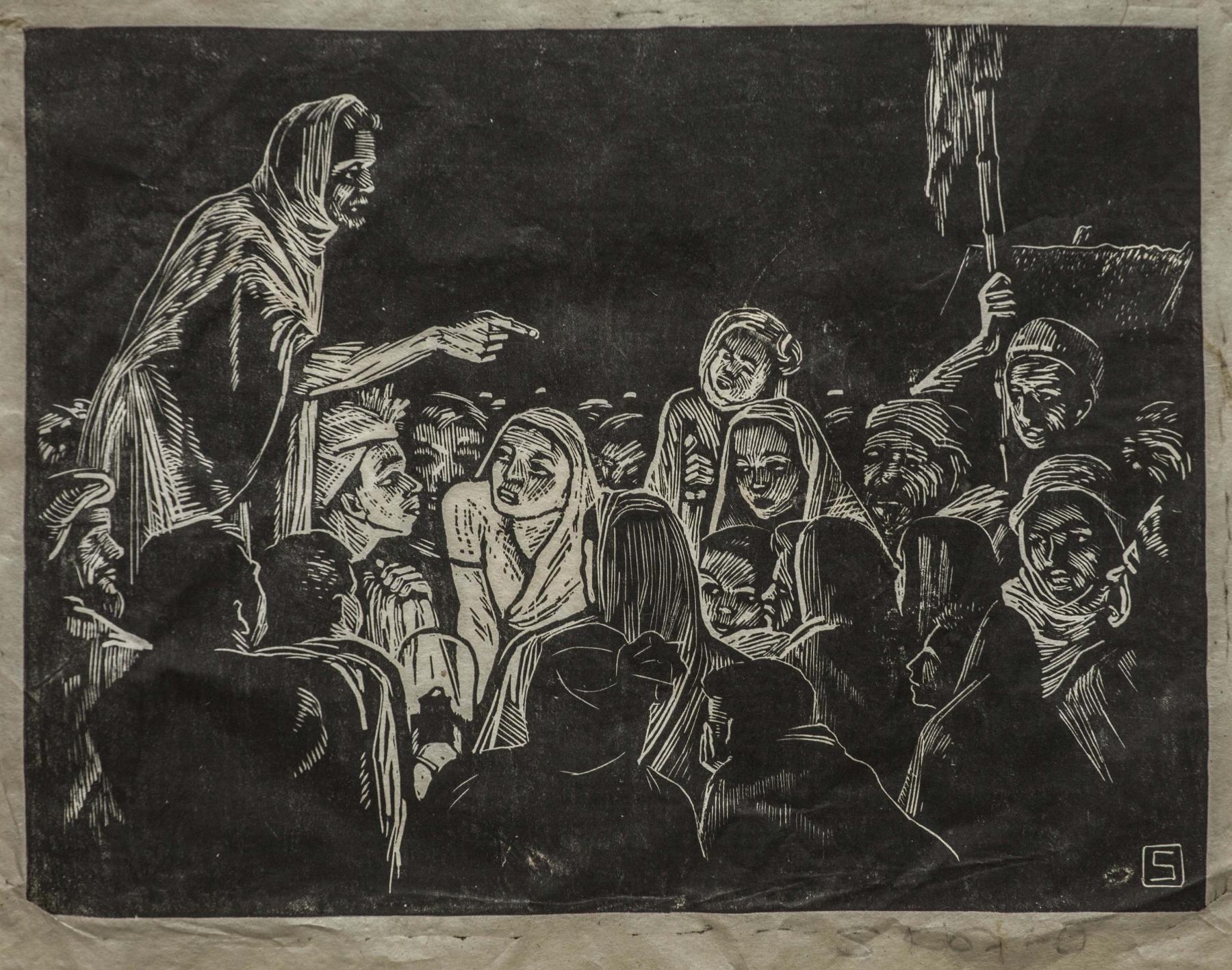

Untitled. Somnath Hore. Woodcut. 5.25 x 6.75 in. Courtesy Akar Prakar.

“People broke into song, ‘Your red flag’s your red salute, O peasant.’”

Friday, 20 December 1946, Tebhaga Diary

‘The pictorial space is a wall but all the birds in the

world fly freely about in it at all depths.’

-Nicolas de Staël

As we gravitate towards a media world that is replete to saturation with the tyrannical presence of images, we have forgotten what it is to be transported to a pictorial space that holds the possibility of flight. This pictorial space—sustained, paradoxically, by a wall, a plane, a flag, or a page from a journal—is reminiscent of the term “dais” that Brecht applied to the bare skeleton or scaffolding of the historically “rich” theatre. This minimal elevation, the simple act of placing a dais, of sketching on the white pages of a journal or making a wall appear—gives us the very frame for seeing something, and without this frame we cannot see a thing.

As I leafed through the Tebhaga Diary of Somnath Hore, I came across this act of minimal elevation—hearing the whispers and cries, slogans and passion of its people raised to the characters of comrades—of a time and a world that are now lost. Through the looking glass of a young artist, I live that time through another body—a body speaking and interacting with revolutionaries who were peasants and students, and believers.

“You are growing rice on your own land, through your own hard work. It’s not ‘tebhaga’ for you; it’s one-hundred percent.”

Thursday, 19 December 1946, Tebhaga Diary

Although Hore's later oeuvre fascinates artists and critics with its special treatment of the tactility of a wound, I chose to stay with his first two works, which were published in the Communist Party of India’s magazine “Janajuddha”, while he was still a student in art college in Kolkata. The years of studentship also coincided with his fateful engagement with the party that he later abandoned, but he never retired the reserve of experiences he had accumulated in those years. In the early 1940s, Hore went to the villages of North Bengal on two occasions: one of these was to participate as a party cadre with the sharecroppers who were fighting against the landowning class for the share of their harvest. The movement—one of the most prominent people-led movements on the eve of the transfer of power that took place in 1947—was called “Tebhaga”, literally translating to “the one-third share”, where the peasants waged a war against their landlords to claim a two-third share of the total harvest that they had laboured over. Their fight was also a way to mark the end of the age-old atrocities perpetrated by the landlords against their subjects, the sharecropping class of peasants. On another occasion, he travelled to sketch the tea gardens of North Bengal and the workers there, which was later published as his Tea Garden Journal.

The Tebhaga Diary was written during his two-week long stay at the villages of Domar and Dimla.

*

“Well, even if I can’t break their bones, I can give them a few bruises, can’t I?”

Friday, 27 December 1946, Tebhaga Diary

These ossified bodies that once glowed with a promise of a future of justice and collective prosperity, are today living in the yellowed pages of historical accounts, exiled to oblivion. But I found here a distinction between the account of the historian, or enthusiasts of historical archives, and the vivacious account of this young artist. His journals are not merely his personal accounts, but they undertake a specific function. When I was reading about Brecht’s theatre in Understanding Brecht by Walter Benjamin, I learnt to appreciate this function as a double function of the “author as producer” of a “condition” of truth to emerge. The author here can produce the conditions of contradiction by the dint of “alienating” or distilling certain gestures, by quoting the commonest phrases of these people initiated into a new cause: the cause of revolutionary transformation of their working conditions. Benjamin spoke of the “crude thinking” propounded by Brecht—which is separate from the subtle “thinking through” and weighing of reasons—where crude thinking enables the utterance of the banal truth in the most ironical way. Crude thinking does not reason so much as it reason-ates: Benjamin terms the school of crude thinking that lives on in a culture as proverbs. We see the ironical drama of class struggle as the sole condition of history being (re)enacted in the pages of the journal: "Every sentence and image (in the journal) was waited for and laid bare. And the waiting lasted until the reader had carefully weighed the sentences and images." This is how I read Brecht’s words on the import of quotation in epic theatre to understand Hore’s artistic impulse behind creating the journal.

Much later, Hore also coined a new mode of thinking—“wound-thinking” [‘kshatachintā’] to describe his artistic process and the internal drama it involved. He confesses that he lived all his life in a “chakravyuh” (maze) of which he only knew of the inception and never found a way out. He found the very material processes of the bite of acid on the etching plate, or the pressing of fingers on the wax sheets for his bronze modelling, as various gesticulations of the same wound, and the condition for his wound-thinking. For Hore, wound-thinking is the very repetitious mode in which he existed all throughout his life as an artist—borne by the memories of witnessing so many wounds in his early life.

*

“‘We’ll harvest the rice tomorrow!’, everyone roared back, ‘We’ll harvest the rice tomorrow! We will!’”

Thursday, 19 December, 1946, Tebhaga Diary

The words of the people are beaded together, interrupted by climactic events and dramatic utterances. The flow of the author's/reader's unconscious perception, rendered by the descriptive account of the ambience of the villages and the people as in a travelogue, is also interrupted by the illustrations that light up the actions, conferring on them a historical truth, elevating the account of the artist into a conscious production. This production is theatrical since it strives to carve a space in time; it is artistic, as it is organized around a central fault-line that distinguishes reality from fiction. The artist steps in and out of his own character in this historical play tantamount to a social movement, much in the fashion of a Brechtian actor.

Brecht says:

“The actor [artist] must show his subject, and he must show himself. Of course, he shows his subject by showing himself. Although the two coincide, they must not coincide in such a way that the difference between the two tasks disappear.”

Hore achieves this balance between the two appearances that must avoid subsumption of one into another. It is this irreducible hinge established through his part-artistic, part-literary production, in the form of a journal that enables future readership to open a window on the struggle of a forgotten people.

One is also reminded of the famous opening paragraph of the Eighteenth Brumaire here, where Marx compares the revolution to a staging of a play:

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.”

“Anyone and everyone will greet you as ‘comrade’ and everyone responds to it. From children of four to old people of seventy they call us comrade and that is what we call them in return.”

Tuesday, 24 December 1946, Tebhaga Diary

The colonizers’ photographic gaze was evident in their choice of representing the “people of India”. The royal portraits had the names of the members of the royal families written below them, whereas the random villagers were classified only according to their ethno-cultural origins. They were nameless, and therefore faceless; but in Hore’s journals, the suturing of the faces with their names, and the roles that these people played within the very moments of these events that are unfolding, elevate them to the status of characters. As Braque notes, these are not mere anecdotes, but they become a pictorial event. This movement from anecdotal reportage to pictorial spacing of an event highlights these unknown people as essentially knowable. This knowability is that of art.

This knowability is distinct from the knowability asserted by a state historian who is abstractly recording accounts of events with these designated “people” blurred of their singularities of bodies, struggling in search for “a dreamful truth or a truthful dream” of living a different “socialist” future together. These singular faces and silenced warriors appear from the dark pits of the past. Memory is lit at once, by the glint of these eyes effectuated by the conscious marks of an artist, which is what makes us believe in these countenances and their struggles. This bridge between faith and memory that takes shape makes these figures real in our perception: These figures are present(ed), and not merely represented. These faces, landscapes, processions and meetings, constitute a certain space with their names and occasions written below, much like scenes and acts in a play. A Spirit that is collectively present along with a “passion for the real” enlivens the characters. They appear in the pages of the journal as characters within a play, staged on the dais of history, as retold through little vignettes of minute actions. They give us a truth, which also carries the semblance of fiction. While telling the story, Hore only introduces an element of belief in their struggle. He tells us about a time—what was happening in the villages, who was reacting in which way, what was taking shape. He noted the way the two sides were fighting, and by taking their verbatim responses and occasionally providing a pictorial view of the reality, he created an artistic universe of a unique moment in time. Without this to-and-fro movement between telling a story and becoming a part of it himself, one cannot tell any truth, for then it is a truth that falls flat without linking itself to the structure of fiction.

*

“The landlord can’t physically remove the land. Can he?”

Tuesday, 24 December 1946, Tebhaga Diary

Hore’s writing takes us into the very interstices, between the bodies of an event, of an ongoing movement. Withdrawing itself from the hall of mirrors of representation, he presents to the readers an ensemble of speeches and images that produce a space-time continuum. How does Hore do it? Simply by quoting people, depicting gestures, and capturing sayings, all of which mark the body of young Hore, who was not unaware of its historical import or its internal logics: the logics of the class struggle. Hore is here the Benjaminian “author as producer”, who maintains a relation to the unknown villagers of Bengal as a figure of traveller or a flâneur. Brecht thought that the creative intellectuals in a society desiring its transformation should participate in the production of relations in a manner that fosters conditions of sighting/citing the contradictions in the society, and thereby “functionally transform(ing)” it to usher in a transformation of social relations.

Contemporary journalism, whether through its words or images, misses the fulcrum of utterances and gestures that make apparent the contradictions embedded in the exploitative social relations, and readily turn them into a ‘spectacle’ that easily feeds into the libidinal enjoyment of the viewers in a cathartic fashion. Consequently, the internal conflict of interests that “stages” this drama of class struggle remains obfuscated, forever out of our “sight”, through a wrapping of the whole contradiction as a commodity. High-speed journalism lacks the ability to make use of this quotable gesture that paves way for the “crude” reasoning, relegating the citizens to the status of consumers enjoying “all-alone”. An artist, such as Hore, is able to distil these by eliminating the unnecessary, whether through acts of choice or by means of his conscious engagement with the society.

Notes

1. Benjamin, Walter. "What is Epic Theater?" in Illuminations. London: Fontana/Collins, 1973: 156.

2. Benjamin, Walter. Understanding Brecht. Verso, 1998: 85-103.

3. Ibid. 81-82.

4. Hore, Somnath. Kshatachinta, Bhangan. Debovasha, 2019: 16-20.

5. Benjamin, Walter."What is Epic Theater?" in Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zhon. Ed. Hannah Arendt. London: Fontana/Collins, 1973:155

6. Marx, Karl. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon. Good Press, 2021: 1-2.

7. Benjamin, Walter. Understanding Brecht. Verso, 1998: 96-100.

Shaon Basu is an archivist and researcher living and working in New Delhi. His research interests include contemporary art and visual culture, philosophy and literature. He holds an MFA in Art History from MSU, Vadodara. His writing on modern and contemporary art and culture has been published in various online platforms and edited volumes such as Serendipity Art Foundation's Write | Art | Connect series; Critical Collective; Conflictorium amongst others.