My plastic hairclips keep shining: A note on erasure, childhood and story-telling

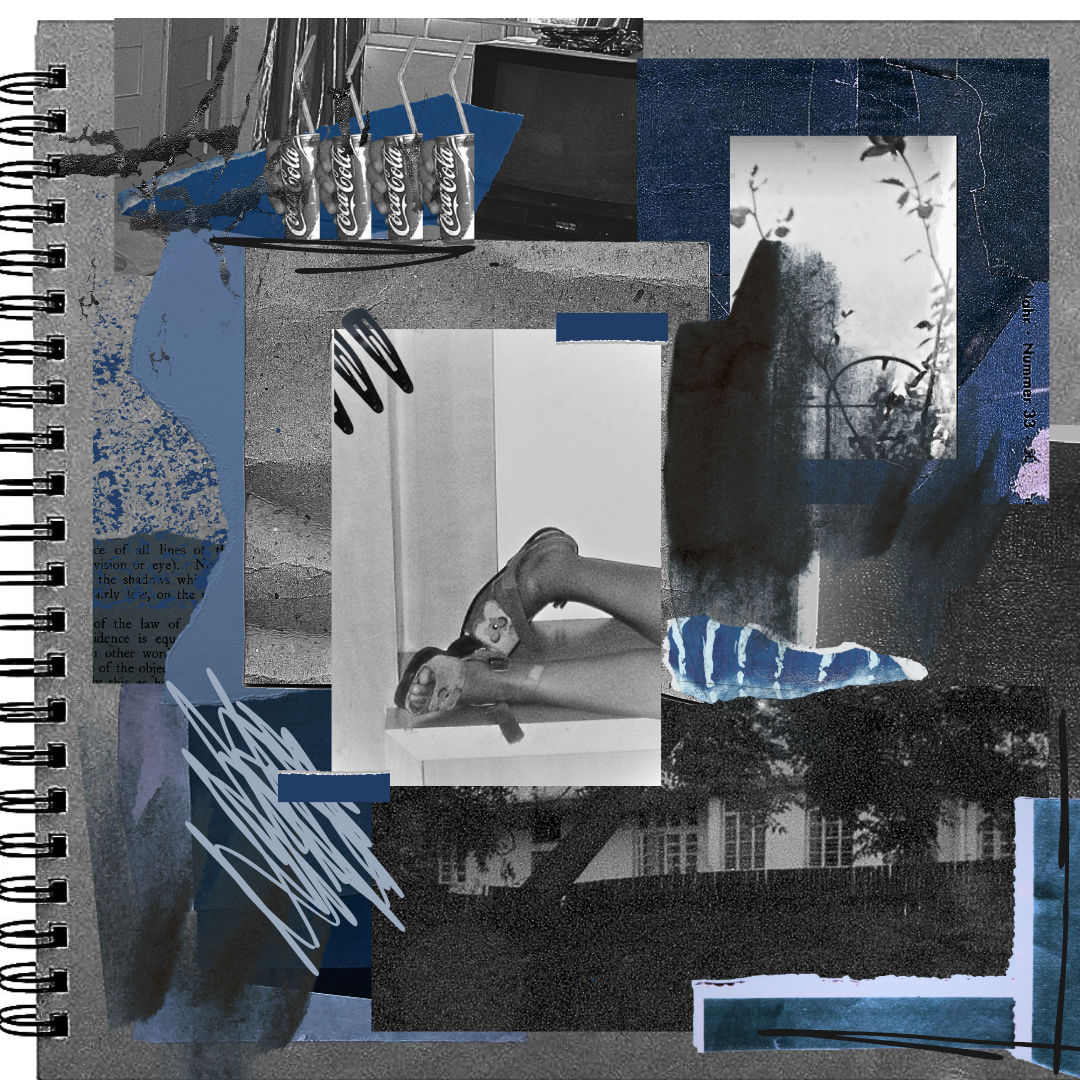

In a small photo album, you know, the kind with slanted yellow font and a studio name, postcard size – you could say, maybe a5 – there are pictures folded from the side or the top, some that are cut or torn.

In this album, the year is 2005, 2006, 2007. The city is Delhi, the Delhi in which the metro is still being constructed station-by-station, line-by-line, the Delhi where Reliance Fresh and Big Bazaar are in terse competition with each other, the Delhi with a winter so foggy that mumma’s Maruti has to be pushed physically so it can take us to school, a winter which doesn’t threaten to kill everybody just yet.

The setting is a government allotted house in Netaji Nagar, a 2bhk home to more than eight people – parents and one of baba’s sisters, one of his chachera cousins, dada and dadi, us two kids. A 2bhk that shares a barbed wire fence with a neighbour who has a big German Shepherd; a fence I cut myself on, a dog I was terrified of.

The setting is also a bigger, ground floor flat in Chanakyapuri with both a front and a back yard, where the green sofa is still green, where my five-years-old sister is still knocking shuttlecocks into the hedges, where my dada is still alive, where aam ka achaar is still made in the kitchen, where my nani is always correcting my hindi homework.

/

In these albums, some images are folded neatly, creased only ever so slightly. Maybe one or two have been cut, or torn. The frame severed, frayed at the edge. I am smiling in the centre, wearing one of many matching outfits, beside my younger sister, who is also smiling. We have ‘boycuts’. We wear the same colours. We go to the same school. We both want to be teachers so we both teach our dolls. There must be a picture of that too.

In another click, we are sitting in the small travelling jhoola that would often stop outside the house, inviting children out for a view of the world that was circular and timeless. Maybe it’s a birthday party, maybe it’s just an ordinary day. Another picture, we stand in our kacchas brushing our teeth. Another, we are mid-dance on our parents’ bed, leaping in the air. Another, the ghost’s shoes appear at the side, or perhaps his hand on one of our shoulders. His nails almost like my own – child-like and colourless.

A picture can only tell you so much. The rest you must remember. The folds and cuts are pronounced against the plasticky hold of each page. Only a third of the table appearing. One half of a clock. My sister’s arm folded away. My shoe cut from view. The dark of the wall snipped.

/

You see, erasure can(not) remove the ghost.

Though the ghost itself has removed so much of me from this story, though the ghost has made this narrative all his very own. Though the ghost owns every inch of every frame, even as he is no longer in it. Though the ghost is unlike any other, having withstood scissors and hands, having withstood time and age, having withstood dream and despair. A haunting is always ever a haunting, isn’t it?

BCcy7u66666666666666666666666666666666666666

66999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999998 –

For the six or seven years that the ghost found me defenceless and all-too-worthy of touch, he took his childhood and mine together in one hand, and he made a fist. He crushed it, like paper, like a sheet that can no longer hold a story, a sheet that crumpled, that is reduced, removed. A sheet without memory is also a sheet without words is also a sheet without a person is also a sheet without meaning is also a sheet without repair is also a sheet about horror is also just a sheet crumpled in a boy’s hand that did what no brother should do.

Wasn’t I erased first? From the years of 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, maybe even 2013, recall is limited, liminal, lost. See the impersonality of it – see the computerliness, see the mechanics, recall, recall, recall.

I distance myself in language. I disappear from the albums.

My plastic hairclips keep shining.

/

Even these photo albums are nothing but a kind of mist. The figures in them removed, the stories they signified stunted, and each picture evaporates upon touch, memory turning its lock on me, all the words lost inside the ghost’s mouth, a grinning gap in one particular photo that is not folded quite so well.

All horror is abstract. All horror lives in the body. I remain in the lurch, going backwards in my mother’s Maruti down the road near Yashwant Place, locked inside a blue tent that came from Dubai as a treat for all the kids, hidden in the bathroom where water dripped into a dark blue bucket, my homework incomplete, my football never reaching the goal post, my small bloomers pulled down.

The ghost is in the album. The ghost is in my life. The ghost doesn’t know how to damn well leave.

The ghost that grew up with you, that taught you to ride bicycles, that played hide ‘n’ seek with you, that shared GI Joes with you, that downloaded English music for you, that was there every vacation, every birthday, every festival and every changing home, a fixture on every map, in each changing city, in every childhood home?

/

You see, erasure can(not) remove the ghost. But somebody older, somebody wiser, took this matter into their own hands anyway. Steady hands over flailing ones.

I can’t tell which parent it might have been, or what year this might have happened. Somebody knew, or was convinced – long before I was - that even if the ghost existed, we no longer had to look at him. We no longer had to allow him into the narrative, or into the frame – aren’t they the same thing after all?

A space to hold a story is also a space to hold a ghost.

A story about a ghost is also a story about the fear of the ghost.

A story is also just that – a story. If you like, it can be rewritten.

The ghost has left our lives like he left our pictures, folded over and worn thin, shredded to bits in a dustbin years ago. What remains of him, after the truth came out, is only hushed conversation between relatives and a series of mutilated images.

Perhaps then, one of the most important gifts given to me by my parents was, not just the folding of pictures or how they were cut up, but what was suggested by the action, which is the (real) subtext, the (real) implication, the (real) meaning:

You are not alone with this ghost, you are not at the mercy of his story-telling, you are not just a small 9 yr old child fixed in front of the camera, a camera that painstakingly documented your childhood and your sister’s, that preserved as much good as it did evil, you are not alone with this ghost, you are not at the mercy of his storytelling. We took the albums and did what we could. The ghost will walk with you all your life, but you know your ABCs well now, and our homes are full of paper.

/

Urooj (they/them) is a twenty-six-years-old queer writer and artist. When they're not working, they're trying to write poems and other kinds of things. They're also a copy editor at Asymptote Journal and they run Dhoopbisscuit, an independent creative zine space.They can usually be found fostering cats, hoarding books, taking pictures and making zines. Get in touch with them on instagram (@storlovsky), even if just to see how often they post about cats.