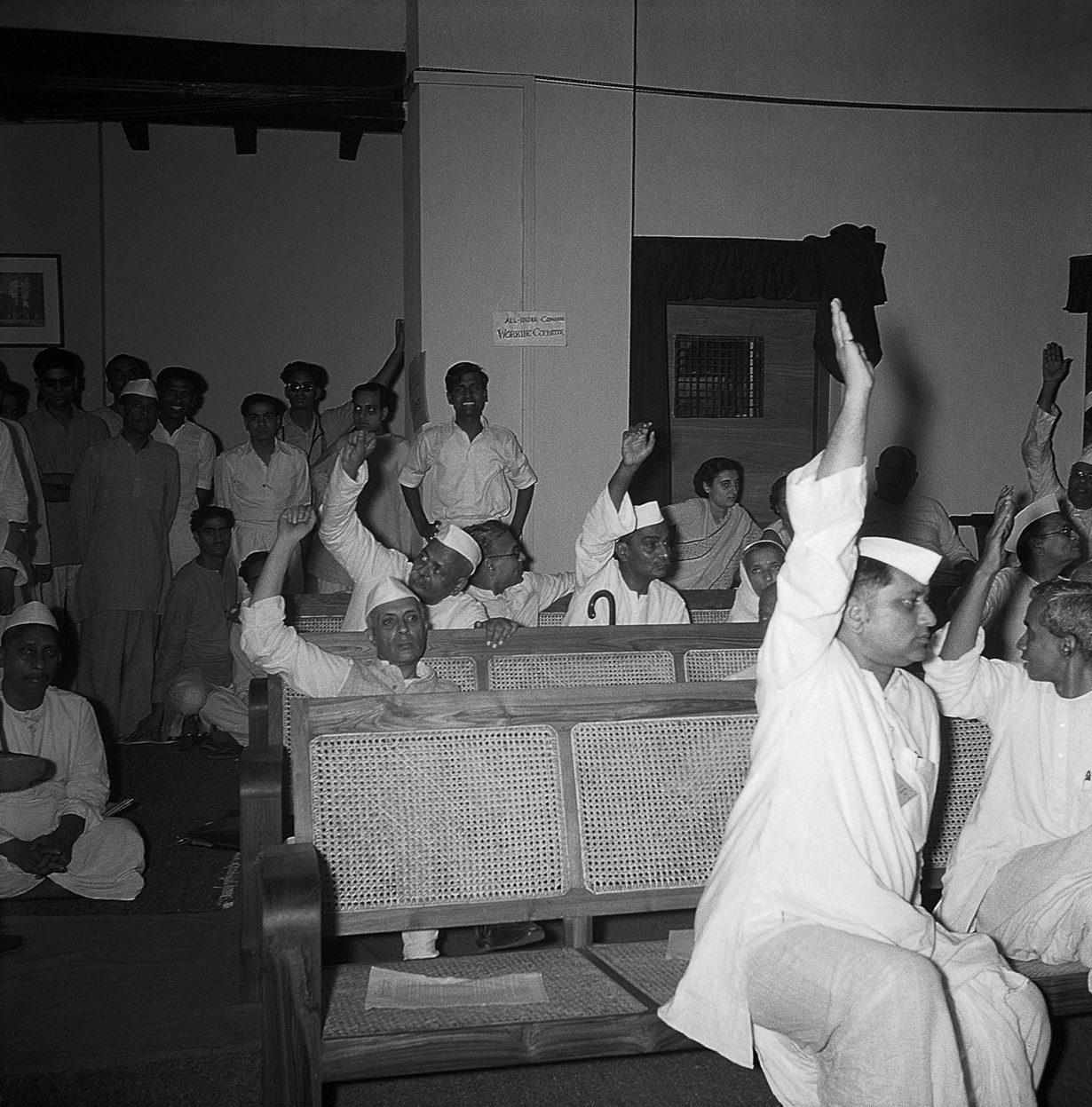

Show of Hands

Homai Vyarawalla, Jawaharlal Nehru at the AICC (All India Congress Committee) meeting to vote for Partition. Dr Rajendra Prasad and Govind Ballabh Pant are seen in the background, c. June 1947. Modern digital reprint from medium format negative, 340mm × 340mm. Courtesy: HV Archive / The Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi, India

The photograph was on view at Tangled Hierarchy 2 from Dec 2022 to April 2023, at TKM Warehouse, Kochi, presented by KNMA and curated by Jitish Kallat.

Ever since he arrived on his ancestral coast, every morning he had jogged to those whitewashed warehouses overlooking the fishing harbour. He was friendly with the spice traders, fishermen, port union leaders, tea vendors, future viswagurus, and everyone else at Bazaar Road. He was acquainted with the town like the back of his hand. He heard a fishing boat captain screaming at the crew in the local language. He hadn’t spoken in his mother tongue a lot while growing up. For him, the mother tongue was more like a phantom tongue. He was brought up in a great metropolis around a thousand kilometres away from there. He thought of it as a story of a peaceful migration, many moons ago, through the west coast to a much bigger harbour city. Not long after the nightmarish mid-century migrations, when burning trains ran into each other, like intertwined snakes on fire. He decoded the scream of the boat captain as something like, “All hands on deck!” Although it was uttered in the phantom tongue, it was a different accent. So rustic, compared to the dignified accent of his parents.

He was in the habit of taking a break from jogging to spend some morning hours in those disused warehouses repurposed as art spaces. He walked up and down, staring at the walls, mentally calculating the spatial dynamics of the leaking interiors, dotted with moss formations, reminiscent of drifting continents. He fantasised about how an installation could be placed if a window was opened to the harbour. He rehearsed the eyes of a viewer wandering around some toy ships assembled in an installation, to the indigo prints of old navy ships as motifs on the flowing white dress of a blonde visitor, to a huge mother ship seen through the window. He made a note that a corner of the warehouse could be partitioned and light-locked, to project a video essay on the differential calculus of liberal democracy over feudal aristocracy. A clenched fist of a peasant. The victory marches. A red star. He told himself that it wouldn’t be lost on the viewers; the matrix of graffiti just outside the warehouses, the thick black outlines of party symbols, clenched fists, and open palms on the whitewashed walls of the spice streets. For him, the spice streets were significant, where some port union leaders bled to death, and some lost their limbs.

After the jog, he got back to his room and took a look at himself in the mirror. A cracked mirror. He was not a narcissist. He smiled at his double reflection. He raised his hand. The mirror images also raised hands. He formed a clenched fist. The mirror images also clenched fists. His eyes drifted to a book on the coffee table, with a painting on the cover in which the painter was looking at the onlooker, in the act of painting a king and queen reflected in a mirror. Inside that cover painting, just near the mirror, there was a doorway with a human figure. Suddenly, he turned the pages of the book. He went through the lines again, in which the twentieth-century author had vividly described the human figure at the door. His eyes narrowed at the lines, “…the ambiguous visitor is coming in and going out at the same time, like a pendulum caught at the bottom of its swing. (…) Pale, minuscule, those silhouetted figures in the mirror are challenged by the tall, solid stature of the one appearing in the doorway.”1

He was struck by the correlation between that painting and the black-and-white photograph he was thinking of installing near that mirror-box artwork in the warehouse. A mirror box designed by a neurologist. He took a closer look at the test print of the photograph. Like there was a human figure at the doorway in the Velasquez painting, there was a lady in front of a closed door in the Vyarawalla photograph. He started to do a head count of the people in the photograph. He noticed that in the foreground, there were nearly eight men seated in three rows of cane-woven three-seater teak chairs. Most of them were wearing Nehru caps, and their hands were raised. He thought that at least one of them was wearing a Nehru cap to hide his baldness from blonde ladies, while others were copycats. Nearly ten men were standing behind the teak chairs, of which only two were wearing Nehru caps, and none of them had raised their hands. He saw that there were only one or two women, in the photograph. They did not raise their hands. He counted the heads again. There were twenty-four heads. And only six hands were raised. And those six were male hands. That too right hands. He quickly scribbled the numbers, six by twenty-four into a hundred. He stared at the number that he arrived at. Twenty-five percentage. That is only a quarter.

After ablutions, he went downstairs to have idlis for breakfast. That was his only meal of the day. He was practising autophagy. He thought that it helped him to think more clearly. He told everyone that autophagy had neurological benefits. He had also selected a neuroscientist, as an artist in the show, for heaven’s sake. Sometimes, he gave his curatorial neurons… a free hand! Laissez-faire of his whorled, entwined neural pathways that were into explorations of hierarchies.

While enjoying buttery smooth idlis, his neurons fired again. In the photograph, why had the lady not raised her hand? She looked to be around thirty years old in the picture. An adult. As it was the mid-twentieth century, even women had voting rights. Then why had she decided not to raise her hand? Did she have disagreements? Only the men seated on the teak chairs had raised their hands, but why? Only they had the right to decide? Who were these pandits? What was she thinking? Why was she looking outside the frame? Who could not have been captured in the photograph? How many more men? Any more women? Who else raised their hands? Why was the photograph in a square format? The technology of that time did not allow a wider lens or a wider format to include more people? Why had she captured that moment as the decisive one? Why were none of the chachas looking at the camera? Of all the men who were standing at the back, at least seven were looking at the camera. Some were gleeful. Especially the one near the pillar, who was having the moment of his life. Were they looking at the camera, or at the photographer? Was she beautiful?

He noticed that there was another framed photograph hanging on the wall just behind the gleeful men ogling at the photographer. He tried to decipher what was in the photograph within the photograph. A meta-photograph, of a tall lady framed by an arch? No! A tall structure against the open sky? A sultanate Minar erected like a raised hand?

He wondered why all of them were wearing white! And only one of them was wearing a Nehru jacket.

Suddenly, he felt guilty that his image analysis was bordering on viciousness, like that of a troll army man. Is it wrong to think critically of these chachas? What was this young woman photographer trying to tell us? He quickly googled the year of her birth. He calculated that she was 34 years old at the time of clicking that picture. Four years older than the only lady in the picture. What was the emergency of clicking that moment? Chacha ka galti? Was our chacha guilty? Do we need to hold on to that nostalgia of the national modern? What is the point of studying political science today, when the entire idea has gone to the dogs? Have we ever been modern?

He started to wonder why he was calculating the age of the lady in the picture, at the time it was clicked. How did that matter? Why was he calculating the age of the lady who was not in the picture, the one who clicked the picture? Why was he interested in the age of these ladies? And only the ladies! Why was he not inspired to calculate the age of the chachas in the picture? Are chachas ageless? Are they timeless?

He finished his breakfast and went out to the bazaar road. It was time to go back to the warehouse. He always reached the gallery space way ahead of all those Leninist curatorial assistants. As he was about to enter the warehouse gate at bazaar road, he saw an unsuspended parliamentarian, who was out for a walk, with thousands. He regretted that there was no time to join hands with them. He went inside the warehouse and unwrapped the framed photograph by the woman photographer of our precious national modern. Show of hands! He noticed that there was someone in the front row curiously looking back at the reaction of a lonely man seated in the second row, slouching, resigned, sunk in his chair, tired, but there was a magnetic empty space around him, whose raised hand was reluctant, whose clenched fist was soft, whose face was not fighting back tears! He felt that it was a photograph of a solemn face assigned to honour a tryst. Inshallah!

Endnotes

1. Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Reprint. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 2007. p.12

Author’s Note: Show of Hands is a short story inspired by a photograph by Homai Vyarawalla, that was shown at the exhibition Tangled Hierarchy 2 in Kochi, curated by Jitish Kallat. The story is imagined as a series of thoughts in a curator’s mind kindled by the photograph. Artist and curator Jitish Kallat composes intriguing spaces as an array of notations with interstitial spaces between the artworks like melodic intervals. While Jitish Kallat juxtaposed the context of the Partition with the concept of the phantom limb in neuroscience, as a meditation on the neuropolitics of a sovereign territorial body, the short story Show of Hands inspired by that curatorial work is about reading a photograph as seen on a gallery wall, in a warehouse, near a water body, as a way of feeling the photograph in its space, while picturing the streets and ships around it.

John Xaviers Arackal has a PhD in art theory, under the supervision of Prof Parul Dave Mukherji from the School of Arts & Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. He is presently serving as Programme Officer of the Arts Practice programme at India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore. He was an Assistant Curator of the fourth Kochi Muziris Biennale in 2018. He taught art theory at Shiv Nadar University, Noida from 2015 to 2018. He curated a group show titled Apple in Dream Mode at Mumbai Art Room in June 2018 and Terra Incognita at the Italian Embassy Cultural Centre, New Delhi in 2015. He also served as Assistant Curator at Devi Art Foundation, Gurgaon from 2009 to 2011. As a self-taught artist, he had a solo show of paintings titled The Rise and Fall of Tigerabad Empire at the School of Arts & Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2012. John was one of the actants in the Five Million Incidents 2019-2020, conceived by Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan in collaboration with Raqs Media Collective.