The Doctor Will See You Now: Love and Grief in Komal Mistri’s Photographs

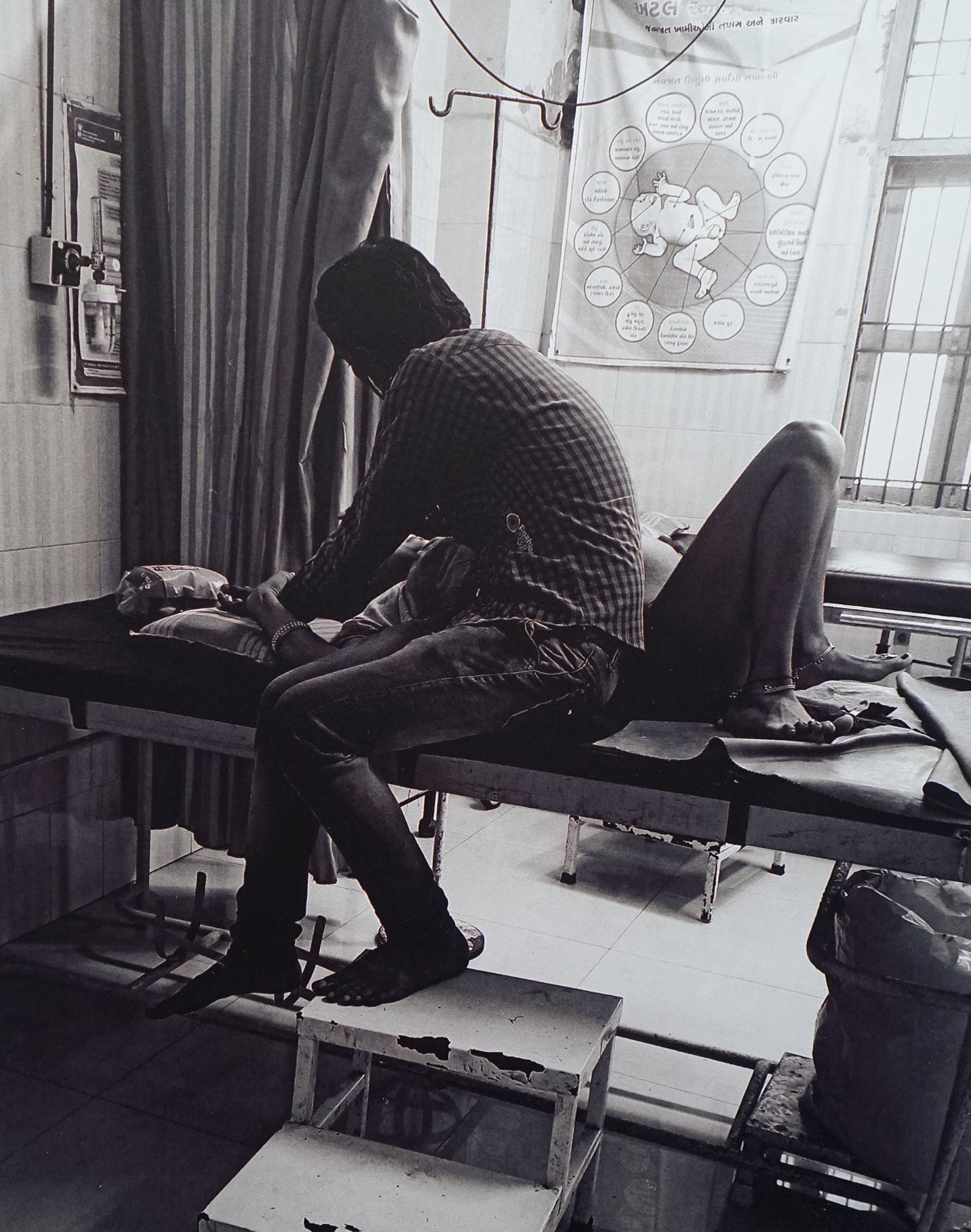

Man in Labour (2022–23. Photograph Print on WP Plywood, 14.5 × 11 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

Among the unflinchingly intimate series of photographs that feature in Komal Mistri’s exhibition Come With Your Own Light at Latitude 28, is an image of near-Baroque theatricality that invites us to the show’s very precipice. Titled Man in Labour (2022–23), the photograph captures a pensive couple, a merging of two bodies; however, it is a union that seemingly rebukes affection at first glance. The photograph, with its sobering monochrome, broods upon a distinct sensibility that seems far removed from any life-affirming excitement. In the tightly-clutched hand of the lying figure rests a sense of distress that longs for support in the face of grief. Mistri’s visual language swells contingency into destiny: the man’s “labour”, an emotionally tender concern for the pregnant woman, becomes a site of exhaustion and vulnerability. This is not an image of sorrow, but of delicacy—of the couple, of the human condition—that narrates or characterises this sorrow. What Man in Labour introduces us to is an instigation, a pulsating awareness of the artist to go beyond what is fragile, the texture-in-pain, and reflect upon a phantasmic space of poetry and anxiety between life and death—not quite alive, yet not quite dead either.

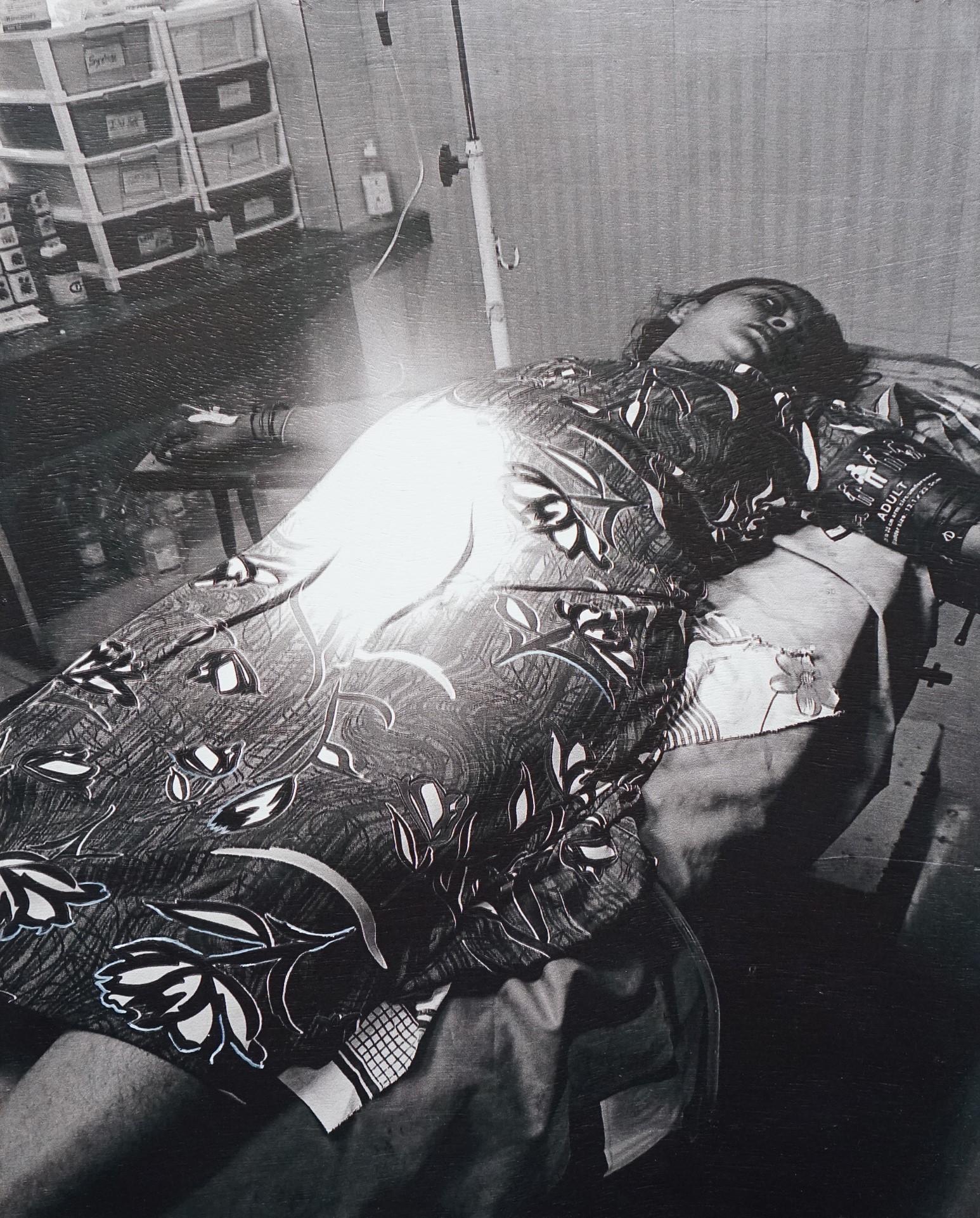

Vase (2022–23. Photograph Print on WP Plywood, 14.5 × 11 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

Come With Your Own Light regards the pain of others with unpretentious care. Documenting the highly ritualistic, celebratory and sacred moment of childbirth in hospitals across Gujarat, Mistri’s craft reveals an alarming suspension of bodies and emotions under bloodied scalpels and surgical lights. Her contemplative photographs gently narrate an unpredictable moment of vulnerability and fear—a transformative event in time that permanently affects our corporeal universe. It is a searing visuality that pushes us beyond the medicinal threshold; we are quietly made aware of a clinical landscape, an invasive surgery room that stitches together lives and destinies. This is where Mistri trains her compassionate eye—for instance, under the haloed, cold light of the examination area, the sedate woman lying in Vase (2022–23) becomes a disquieted cruciform, a body surrendered. In its near-lifeless, flaccid vision, the image arbitrates between life and death. The artist’s interest lies less in the performance on the table, but instead seeks to draw our attention to the woman who, outside the image, can go through this extraordinarily sobering event. It is an enigma of concern that Mistri highlights with great care.

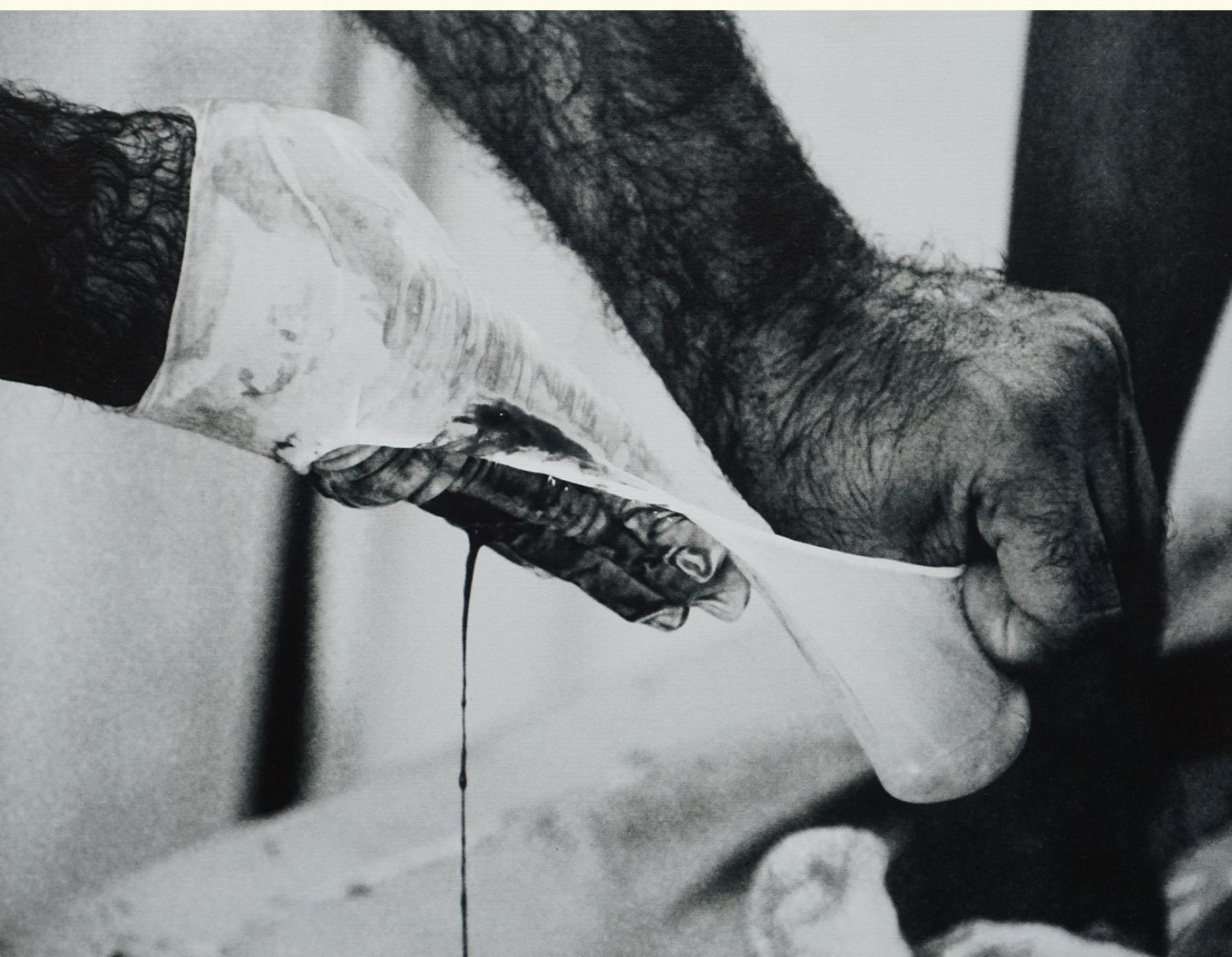

Removing (2022-23. Photograph Print on WP Plywood, 10.5 × 13.5 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

Mistri’s photographs—assemblages that memorialise the lives of her subjects through ephemeral objects—are ineffably haunting. In their intrusions over anaesthetised skin, ruptured gloves, sanguine gowns and rousing wails is a photographic process that tacitly subverts our gaze: lucidity is muddied with abstract forms, a moment of rest is sullied by the spilling of blood and care is overridden by fear. Removing (2022–23), for example, introduces a detail—the removal of surgical gloves—that is seemingly so trivial yet tangible, that it is impossible to relax against the image of the outstretched rubber. A breathless silence settles around us while we wait for the elastic to give away. Impatience lingers around the frame, acutely pulling our attention towards the thick spattering of blood. What happened here? With its burly hands, Removing is an uncomplicated, direct photograph of a complicated, difficult subject. It is the craft of a “confidante, a listener to the woes, injustices and happiness of her women subjects,” as Saloni Jaiwal’s curatorial text describes Mistri; an artistic practice that comes across what the artist captures with a cool, quiet confidence. The camera, with its lens exposed to a special kind of gore, does not shake or falter, remaining trained on the subject with carefully considered ease.

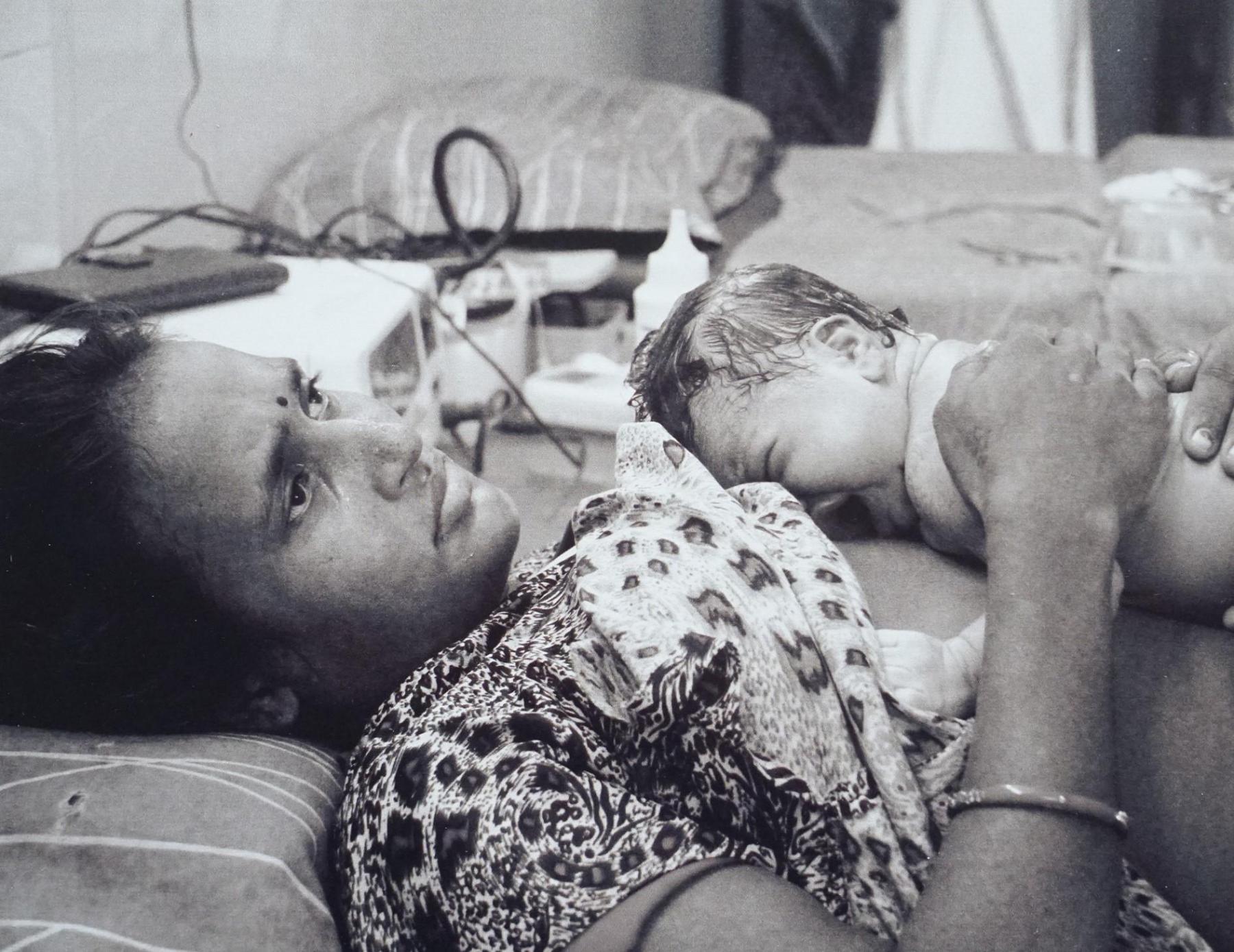

Beginning (2022–23. Photograph Print on WP Plywood, 10.5 × 13 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

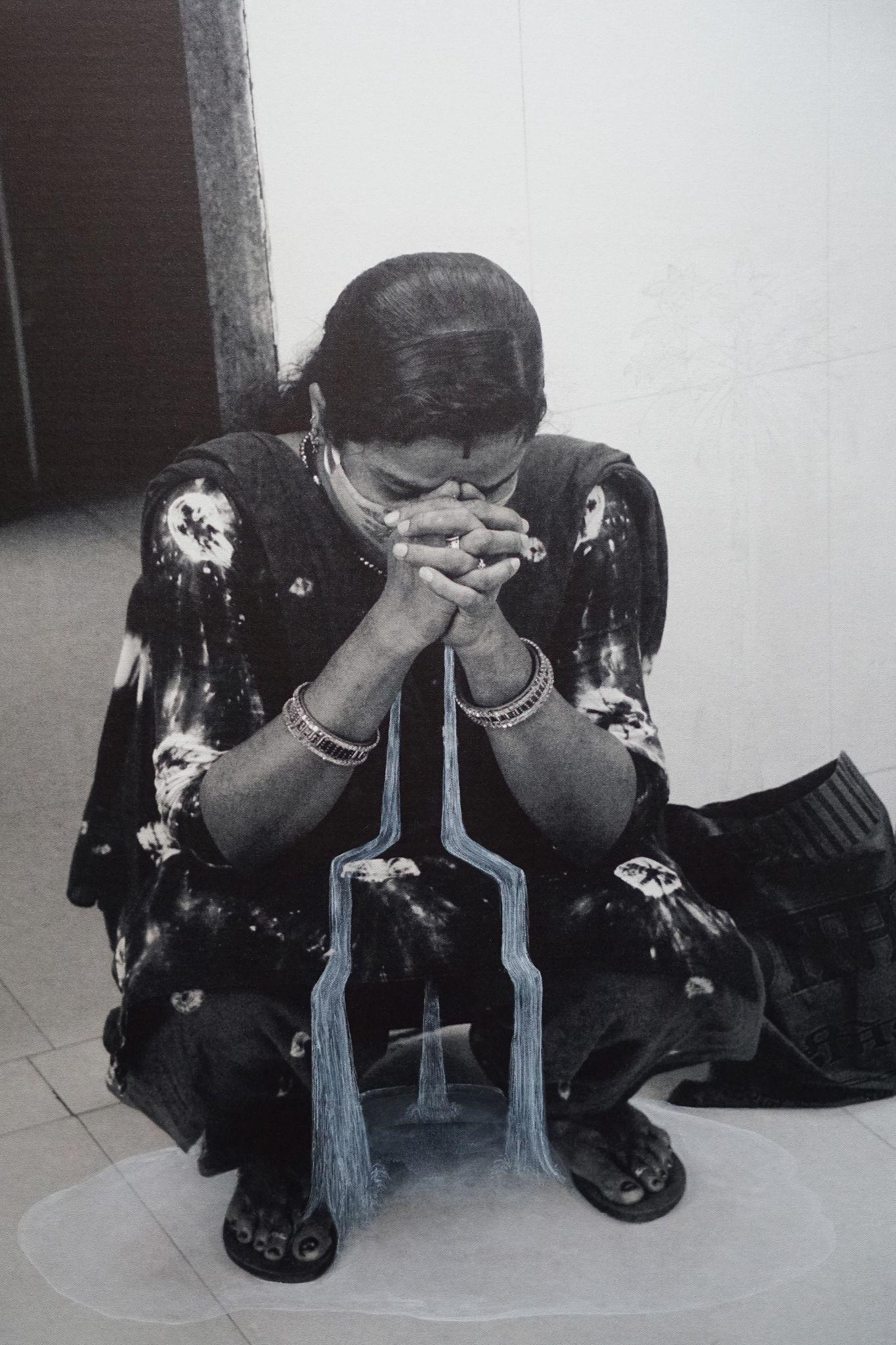

If “In the beginning was the Word,” in Beginning (2022–23) the word is nowhere near God; it is deftly impermanent, mortal. In the listless gaze of the mother cradling her newborn, we come across a photograph that captures the painful tiredness of the maternity ward, an exhaustion that numbs our collective senses. This is a visual language that asks, can photographs immortalise suffering? What ties Mistri’s photographs together— explicitly or otherwise—is pain. In this detached, clinically challenging environment, suffering becomes the great equaliser. This is hauntingly obvious in Cry (2022–23), where a squatting, expecting mother settles down pensively, in grief. The profound tenderness with which Mistri approaches her subjects mournfully reminds one of Peter Hujar’s photographic series Portraits in Life and Death. The slim catalogue carries Susan Sontag’s sharp words that reflect on this feeling:“Photography also converts the world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also—wittingly or unwittingly—the recording-angels of death.”

Cry (2022–23. Photograph Print on Canvas, watercolour, 38 x 24 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

It is difficult to navigate Mistri’s photographs—scar tissues that embody kindness and suffering—as merely grotesque abjections. Nor are they sympathetically romantic or merely “beautiful.” In the exhibition’s womb-like display of stretch marks and serrated gashes on the walls, we open up to a Brutalist operating theatre—a maternity ward that negotiates a cold, discomfiting bravado with a tenderness that does not isolate these images as the medical other. It is a melancholy that stays alive in the face of despair and dread. Beneath this frailty is Mistri’s subject—the abject body, ineffectively protected by the taffeta of operating room gowns. It is a maternal instinct that perseveres through an apathetic healthcare system and structures of inequality to comfort us as Holding (2022–23) does: a painfully powerful and quiet reassurance that asks us to seek our own light.

Holding (2022–23. Photograph Print on WP Plywood, 14 × 11 inches, Edition 1 of 4.)

To read more about practices that investigate the corporeal and medical aspects of the human body, read Shankar Tripathi’s essay on Zahra Yazdani’s work and Mallika Visvanathan’s essay on the use of medical imaging in video art.

All images are from the series Come with Your Own Light (2022–23) by Komal Mistri, courtesy of the artist and Latitude 28.