Ecology, Crime and the State: The Sovereign Forest

As one enters the top floor of the Nepal Art Council building, a non-profit art space in the heart of Kathmandu, one is led to a momentarily disorienting experience. From the bright outside world, visitors to The Sovereign Forest exhibition part black curtains to enter into a space almost devoid of any natural light. All of the walls, even the high ceiling, are painted black, with only small lightbulbs offering the bare minimum light to help viewers orient themselves. The exhibition, facilitated in Kathmandu by photo.circle, has been consciously presented in this sombre manner, magnifying the themes of the exhibition.

The Sovereign Forest is an ongoing multimedia installation and engagement, helmed by Amar Kanwar in collaboration with Sudhir Pattnaik, Sherna Dastur, and the organisation Samadrusti. While The Sovereign Forest was first exhibited in August 2012 at Bhubaneswar, Odisha (formerly Orissa), it has since witnessed various permutations and combinations of displays and installments. Encompassing documentary film and multimedia works, the exhibition chronicles the resistance movements of Odisha’s indigenous and local communities against government entities and corporations. These movements—over the control of agricultural lands, forests, rivers, and mineral resources—have been waged in the area since the 1950s.

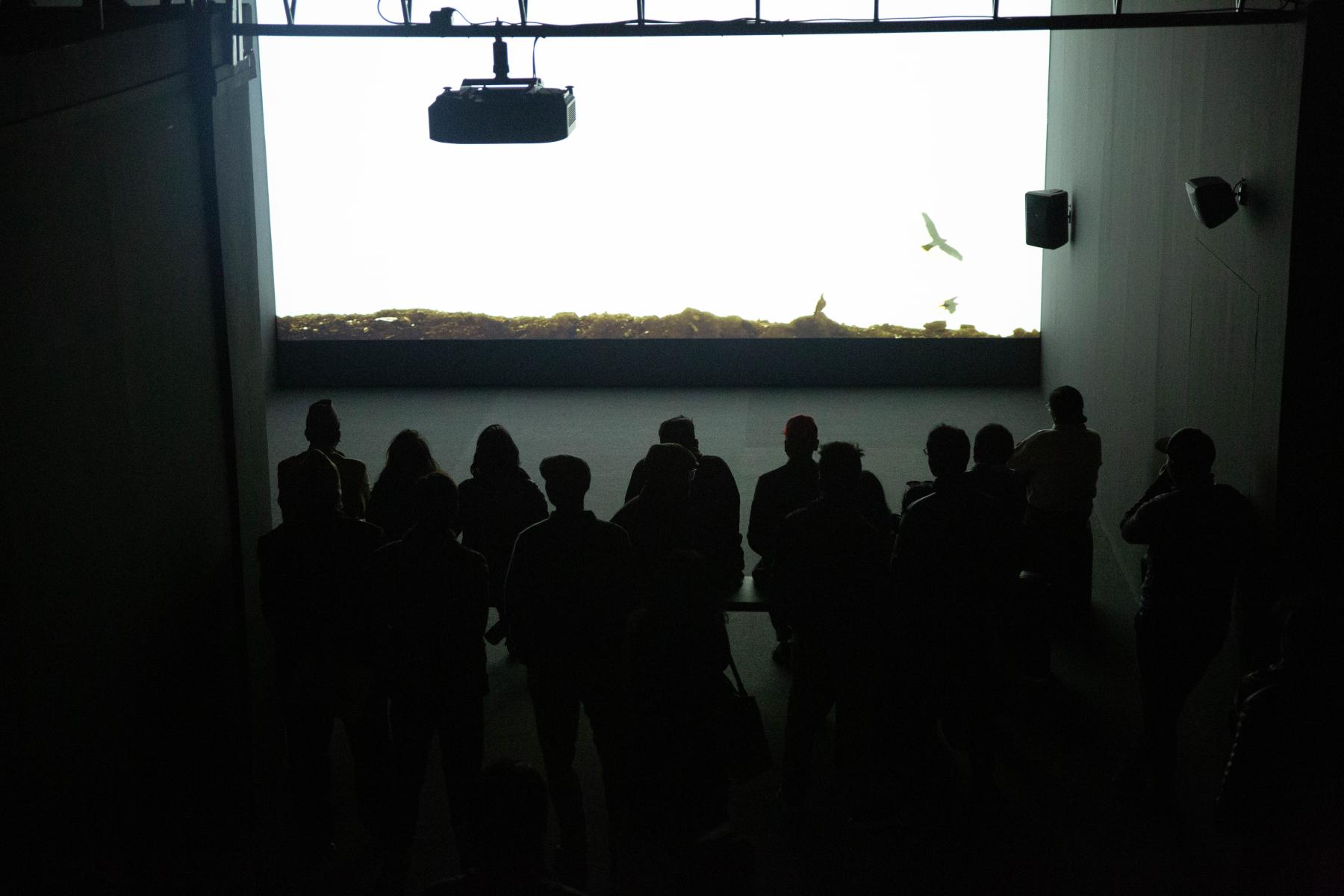

The Scene of Crime, a 42-minute documentary film, offers an alternative way of looking at evidence of exploitation of natural resources as well as indigenous knowledge and history. (Photo credit: Amit Machamasi/photo.circle)

The exhibition is loosely divided into four sections: a screening space for Kanwar’s film The Scene of Crime (2011); a library room containing The Counting Sisters and Other Stories (2011), The Prediction (1991–2012) and The Constitution (2012); a seed room; and an investigation room. Each node of the exhibition offers a different vantage point for observing, witnessing and experiencing the resistance movements of countless local communities in Odisha. Through fiction, film, paddy seeds, photo albums and other interactive elements, the exhibition delves into the nature and aftermaths of conflicts over natural resources.

The Constitution consists of ten chapters titled as "the tree of rain", "the tree of ancestors", "the tree of insurgency", etc., and whose pages are interwoven with Odisha’s indigenous symbols such as fishing nets, ropes, knots and cloths. (Photo credit: Deepa Shrestha/photo.circle)

At the heart of the exhibition is the assassination of Shankar Guha Niyogi on 28 September 1991. Niyogi was the leader of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, a collective comprised of organisations of workers, peasants and tribals. Niyogi had ‘predicted’ his assassination and had invited Kanwar to Bhilai to document the people’s movement. Kanwar arrived the day after the assassination and instead documented the aftermath of the killing in his film Lal Hara Lehrake (1992) as well as The Prediction (1991–2012), the latter of which is included in the exhibition. The murder case of Niyogi dragged on in courts for fourteen years, finally culminating in a 2005 judgement by the Supreme Court of India, where they convicted the hired assassin Paltan Mallah on a life sentence while acquitting five people—Moolchand Shah, Chandrakant Shah, Gyan Prakash Mishra, Abhay Singh and Awadesh Rai—who were alleged to have conspired against Niyogi. However, the case of Niyogi is not an isolated one. There have been innumerable locals who have been injured, maimed, or murdered by goons or government forces in retaliation.

In his documentary film The Scene of Crime (2011), Kanwar ponders the themes of justice, violence, and the validity of evidence. After a crime has been committed, who gets to decide what is valid or invalid evidence? And what if they are wrong? “Almost every image in this film lies within specific territories that are proposed industrial sites and are in the process of being acquired by government and corporations in Odisha,” the film declares at its beginning. Divided into seven chapters or “maps”, The Scene of Crime provides glimpses of slow-paced daily life in Odisha: the swaying of tree branches by the wind; fisherfolk casting their nets into the sea; a group of women sitting underneath the shade of a tree; groups of workers sitting around as people chat animatedly; and so on. Similarly, Love Story (2010), another film by Kanwar, depicts silhouetted figures of people and machines at work. This portrayal of the extraction of resources is juxtaposed on top of a love story that carries on through texts on the screen. One such text reads, “The suddenness of your departure is hard to believe,” pushing one to wonder about the relationship between love and the loss of indigenous lands, forests, water, history and identity.

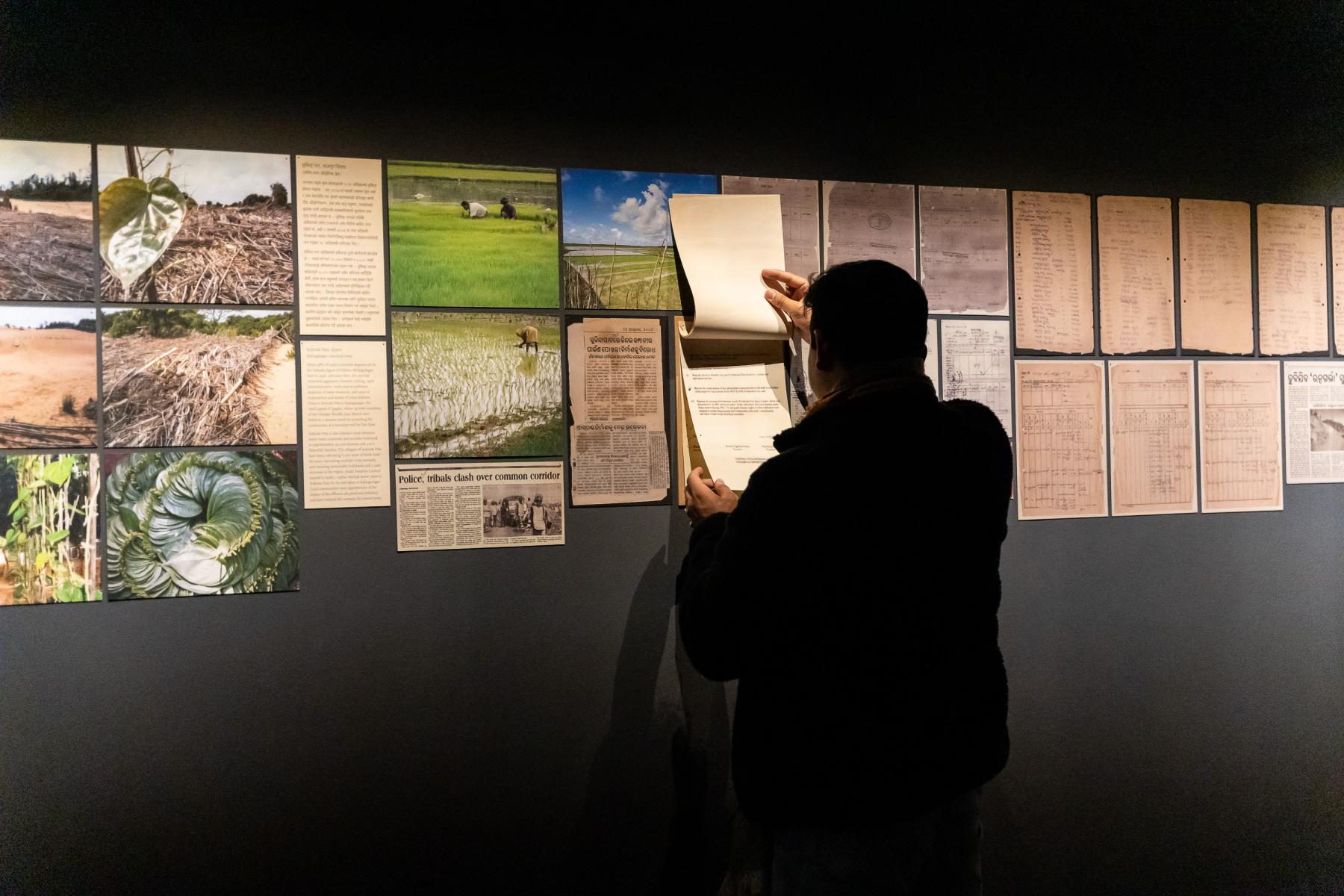

On the walls of the investigation room, there are collections of newspaper clippings, photographs, land deeds, etc., all pieces of evidence that were contributed by the local people and communities of Odisha to The Sovereign Forest exhibition. (Photo credit: Deepa Shrestha/photo.circle)

The exhibition, in its totality, feels like a book that keeps its secret close at heart. There are no easy, linear, spoon-fed narratives to be found here. The Sovereign Forest does not hold the hands of the viewers to portray why the exploitation of natural resources is bad or how the lives and existence of local communities are interwoven with the very lands, forests, water sources and sky they inhabit. Take, for example, The Counting Sisters and Other Stories, which recount cryptic tales of a group of sisters who record the deaths of people. The epilogue of these tales lies in audio form in the “investigation room”, where a lone bulb hangs from the ceiling, mimicking the investigation room of police stations commonly depicted in films.

In the middle of the investigation room are audio recordings of epilogues to the stories contained in The Counting Sisters and Other Stories, which combine textual elements of the exhibition with audio elements. (Photo credit: Samagra Shah/photo.circle)

Elsewhere, the seed room presents 272 varieties of traditional paddy seeds, a small portion of the 30,000 varieties that were once cultivated in the Odisha region. All of the seeds were painstakingly and lovingly grown by Natabar Sarangi, a seventy-year-old farmer and seed activist from Narisho village, especially for the exhibition. The room also contains a “Seed Book” containing the names of the variety, duration, land elevation, production per acre, and end uses—an act of documentation and preservation in the hope that “…if we are able to look again, we may understand again.”

However, here too is the contrast between different ways of resisting the erasure of local communities' history and identity. While the seed room’s three walls are patterned with small wooden ledges full of seeds, the fourth wall contains five photographs of resistance movements and another three photographs of martyrs along with two photo albums. Photo Album 1 shows the Lying Down Protest that occurred on 11 June 2011, where villagers of Dhinkia, Gadkujang, Govindpur, and Nuagaon in Jagatsinghpur district in Odisha protested against the state government and the Korean steel company POSCO. Photo Album 2, on the other hand, is far more grim, showcasing the aftermath of the conflict between Kalinganagar locals and government forces on 2 January 2006, where locals were killed and their bodies mutilated.

The seed room, while containing only a fraction of the 30,000 varieties of paddy seeds that were once found in Odisha, showcases how documentation is vital to resistance and preservation. (Photo credit: Amit Machamasi/photo.circle)

In many ways, the exhibition outlines the atrocities committed against the local and indigenous communities in Odisha. The exhibition also harkens to the indigenous movements in Nepal, tying in with the efforts to recognise land rights and formalising the recognition of the nation’s varied ethnic groups and claims to equal rights and protection. Following the fall of the monarchy and subsequent establishment of democratic processes from the mid 2000s, indigenous communities have rallied for the protection of cultural and political legacies and preservation of localised knowledge. Through its various forms and interventions, The Sovereign Forest reiterates the constant need to engage with not just recent histories but the ongoing resistance efforts against the destruction of existing cultural and political mobilisation in favour of homogenous, capitalist extractions.

To learn more about Amar Kanwar’s work, read Mallika Visvanathan’s reflections on Kanwar’s installation The Torn First Pages (2004-08). To learn more about artistic work around indigenous people’s movements and ecology in Nepal, read Anisha Baid’s essay and curated album on The Skin of Chitwan (2021–) by Nepal Picture Library, a series of conversations with Subash Thebe Limbu and an interview with the team of KTK-Belt from PhotoKTM 2023.

All images are exhibition/installation views of The Sovereign Forest, on view at the Nepal Art Council. Images courtesy of the artists and photo.circle.