A Preoccupation with Time: Revisiting Amar Kanwar’s The Torn First Pages

Installation view of The Torn First Pages at Haus der Kunst, Munich. (Marino Solokhov. Munich, 2008.)

Artist and filmmaker Amar Kanwar’s body of work—spanning four decades—has consistently responded to conflict by presenting and archiving evidence. The Torn First Pages (2004–08) is a multiscreen installation consisting of nineteen channels playing on loop. The work is divided into three parts consisting of three metal frames from which pieces of paper are suspended. The pieces of paper—which offer themselves as screens on which the multiple films play—are distributed on the frames in a manner which suggests that the frames are open books. The form of the installation is inspired by, and an ode to, a simple act of resistance: Ko Than Htay, a bookseller in Mandalay in northern Myanmar was accused of tearing out the “first page” from books in his shop. These first pages contained the slogans and anti-democratic propaganda of the military regime mandatorily published in all books. For this defiant act, he was arrested in December 1994 and sentenced to three years in prison.

Taking this incident as a point of entry, Kanwar’s intervention takes the form of a certain kind of preoccupation with time which he poses as “…the formal presentation of poetry as evidence in a future war crimes tribunal.” He explores the sensory experience of time in multiple ways by constructing and manipulating the moving image, thus creating different experiences of meaning making through such treatment.

Installation view of “Part One” of The Torn First Pages at Haus der Kunst, Munich. (Marino Solokhov. Munich, 2008.)

“Part One” consists of six sheets of paper and includes the films “The Face,” “Ma Win Maw Oo,” “Thet Win Aung,” “The Bodhi Tree” and “Somewhere in May.” While the first three play in synchronised loop and have the same duration (four minutes thirty-five seconds); “The Bodhi Tree” runs for seven minutes despite being on the same side of the frame. “Somewhere in May” is projected on the right side of the frame, singularly, and has a duration of thirty-eight minutes.

On the left side of the frame, the top most projection is that of “The Face” which revolves around the visit of General Than Shwe, (then) Supreme Head of the Burmese Military Dictatorship, to India in 2004. Kanwar’s camera seeks out the dictator upon his arrival in order to reveal the somewhat mysterious leader, but as text tells us “Cameras are not allowed.” Taking the footage that he managed to shoot, Kanwar excavates it to reveal the leader’s face—zoomed in and grainy—on which the title appears. The following day, the dictator visits Gandhi’s memorial in Rajghat. Keenly aware of this performance for the farce that it is, Kanwar replays the photo-opportunity of the general throwing rose petals over and over. The bizarreness of this charade is highlighted through the acceleration of time, resulting in the sound of the hymn Vaishnava Janato becoming frenzied and sounding higher and higher with each loop. As the music fades out, we are left with a very different “face”—a person who we imagine is one of the thousands of nameless victims of the general’s rule. The faces of those oppressed under the military regime as the lingering (or flickering) last image repeats in the other works in this part as well. The repeating motif binds the viewing experiences together, reiterating the very real consequences of military rule.

Installation view of “Part One” of The Torn First Pages at Haus der Kunst, Munich. (Marino Solokhov. Munich, 2008.)

Another victim of the military junta was Ma Win Maw Oo. A high-school student, she was shot and killed in the military crackdown on protesters in September 1988. The moment in which she was carried by two medical students became a news photograph that found worldwide recognition for a brief period before disappearing from public memory. The photograph, however, continued to circulate in underground circuits of the pro-democracy movement. Addressing this shift, Kanwar’s film of the same name breaks down the photograph into fragments—distilling the event into disembodied faces or blurs of red and brown that defy easy meaning. The moment of frenzy appears years later as pixels that persist—gesturing to the manner in which the photograph was repeatedly copied and shared within the Burmese community as an act of remembrance.

Still from Ma Win Maw Oo.

“Thet Win Aung” consists of two projections side by side playing out as mirror reverses of the same footage. It begins with the image of hands in the act of doing something—gently revealed to be hanging up a portrait of Thet Win Aung. Aung was a student leader who was sentenced in 1999 to fifty-nine years in prison. Kanwar stretches out time, trying to imagine the experience of living in jail for what is, to him, the longest time imaginable. The slowed down moving-image creates a hypnotic effect that breaks with the revelation of Aung’s institutional murder in 2006.

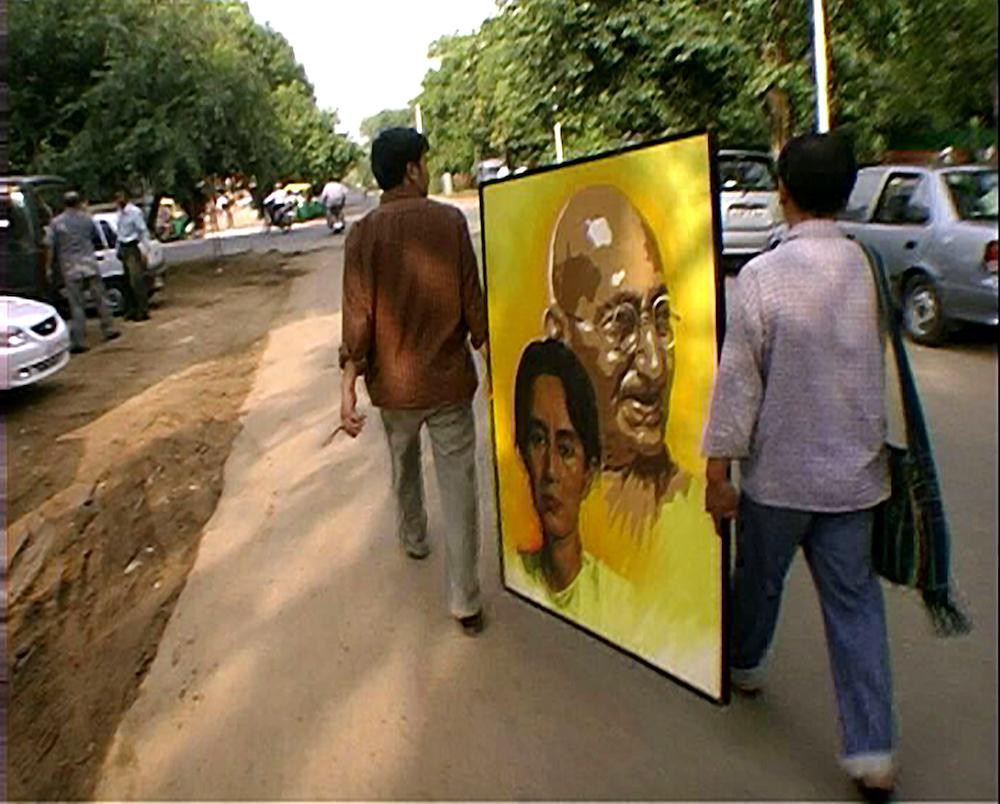

“The Bodhi Tree” follows the logic of documentary time. Kanwar observes Sitt Nyein Aye—a dissident painter, who escaped to Delhi—as he works in his studio, carries a painting of Aung San Suu Kyi and Gandhi within the same frame and joins a protest against the Burmese junta. The mode of documentary time links South Asia’s varied pasts through interconnections between prominent figures such as Buddha, Gandhi and even Aung San Suu Kyi in the recent past.

Still from “The Bodhi Tree.”

On the other side of the frame is the film “Somewhere in May.” Shot in Oslo in 2005, it initially feels far removed from the rest as we see (white) people go on with their lives, once in a while punctuated by text that refers to what is happening in Myanmar. Slowly the narrative of what is happening in Myanmar seeps into the sonic as we hear a conversation in Burmese where a woman narrates her experience of having visited prison. The image then reveals the studio of the Democratic Voice of Burma Radio Studio in Oslo and we see the ways in which resistance in the form of remembrance and circumventing censorship finds place in the lives of those in exile. The artist’s preoccupation with time here is centred around trauma and its telling.

Kanwar’s experiments with time and meaning-making bring together different experiences of the past and the present. This elasticity of space and time allows us, as viewers in the present, to be reminded of the cost and consequences of such political upheavals as they create ripples in South Asia and the world. In a time in which the surfeit of images has made us increasingly desensitised to violence, the artist pushes us to acknowledge the narratives that managed to escape the harsh censorship in Myanmar. Perhaps Kanwar’s work can serve as a reminder of how acts of violence shall not be forgotten but persist through image-making and practices of circulation.

To read the second part of this post, please click here.

To read more about Myanmar, please click here, here and here.

All works by and courtesy of Amar Kanwar.