The Zamindars of Bengal: Looking at Santanu Dey's Lost Legacy

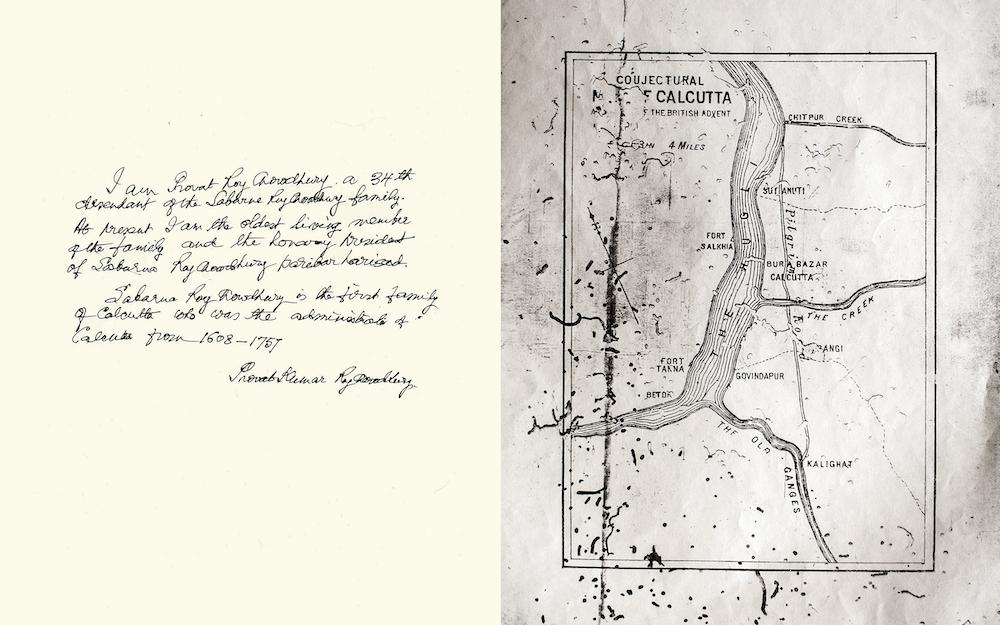

Left: A written declaration by Pravat Kumar Roychoudhury, the oldest living descendant of the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family. The family was one of the oldest Zamindar families of Kolkata.

Right: One of the oldest maps of Kolkata made during the British rule. At the time, Sutanuti, Gobindapur and Kalikata combined to form the city of Calcutta.

The arrival of the British East India Company in India, in the seventeenth-century, led to several changes in the social order and the policies that governed the country. One such policy was the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, which led to the establishment of the Zamindari system, allowing sections of wealthy Indians to own large portions of land. The hereditary landowning system allowed the Zamindar families to benefit from privileges and wealth as well as have control over peasants and agricultural workers, from whom they collected tax to aid the growth of the colonial rule. Following the independence of India in 1947, one of the first major agrarian reforms introduced by the government was the Zamindari Abolition Act in 1950. The new policy led to the privileged section of society to lose their status and a large part of their wealth overnight. In Lost Legacy, Santanu Dey explores the lives of the descendants of the Zamindars in the era of the decolonised, independent India.

Portrait of the Sil family during the colonial period.

The Sil family was a well-established Zamindar family of erstwhile Calcutta, with its founder Motilal Sil being an influential and wealthy businessman during the colonial period. Photographed here is Amar Mallick, a sixth-generation descendant of the Sil family, at his residence.

A visual artist and independent photographer based in Kolkata, Santanu Dey’s work explores mythology, culture and socio-political issues, often locating itself at the intersection of art and documentary. Dey received the Social Documentary Photography Grant awarded by the MurthyNAYAK Foundation and SACAC in 2019 for Lost Legacy. The grant—launched in 2018—encourages work made with a sociopolitical intent. In his artist statement, he writes: “Overnight the status of these aristocrat families changed on 15 August 1947, the day of India's independence. The privileged class of society were reduced to ordinary citizens of India. Like their fellow countrymen, they took on various employment services for survival.”

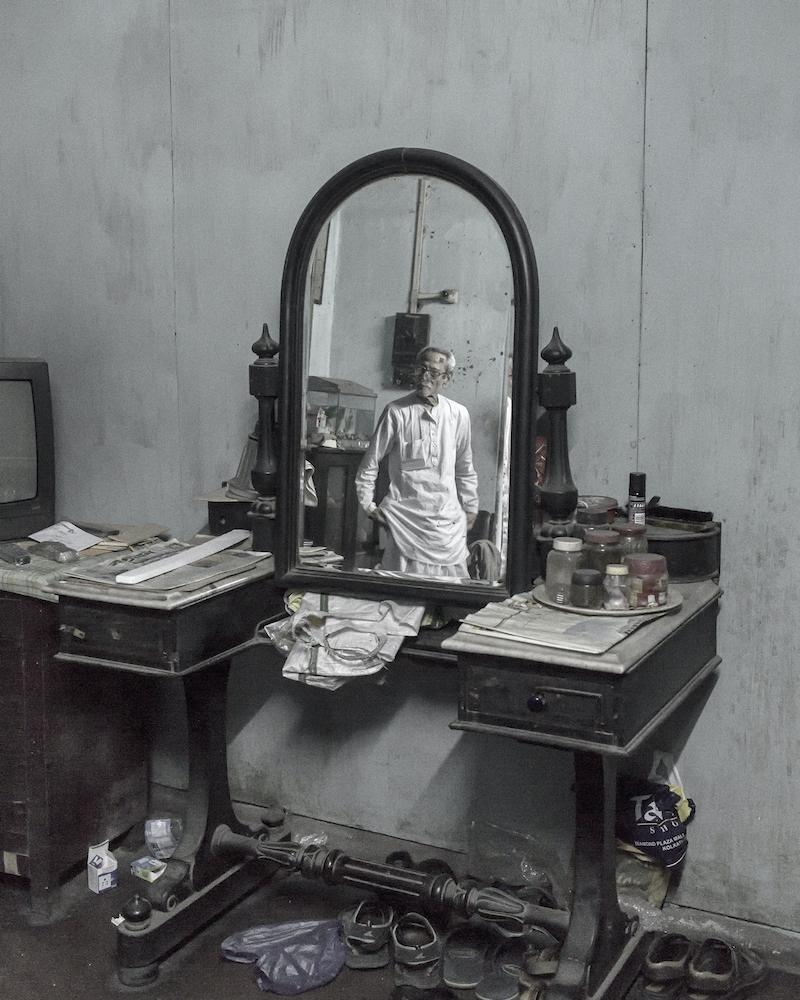

In an interview, Dey explains how the partition of the subcontinent has been an important site of exploration in his work, making Lost Legacy the first part of a trilogy that looks at the social and political effects of the partition and decolonisation in an independent India. Lost Legacy explores the sociocultural landscape of Kolkata in contemporary times by turning the lens on its Zamindar families. The artist begins with questions about power and prestige and initiates conversations about the former elites of Bengal. Building an archive of photographs, maps, found images, handwritten notes and testimonies; Dey draws parallels between the erstwhile Zamindars of Calcutta and their descendants in the present-day Kolkata.

Left: Portrait of early members of Kalutola Rajbari.

Right: Portrait of Nrishingha Mullick and his wife, the eldest living descendants of Kalutola Rajbari.

Dey’s series traces—and archives—the rise and fall of the Zamindars. Photographed inside weathering homes, the descendants still yearn to hold on to their past status and standard of life. In the present, as the agricultural community protests against the recently passed farm bills, it is essential to understand the history of agriculture and landowning as well as the implications it has had on those who work and earn their living from the soil.

All images by Santanu Dey. From the series Lost Legacy. Kolkata, 2019. Images courtesy of the artist.