Digital Flânerie: The Garga Archives in the Contemporary

Ezra Mir on the set of a Madan Theatres' film.

Initially conceived as a book, the Garga Archives emerged from sustained interaction between Anuj Malhotra of the Lightcube film collective and Donabelle Garga—wife of late filmmaker and historian Bhagwan Das Garga, on whose collections it is built. The website serves as an alternative model for an archive, with a deliberate absence of visible contours to demarcate the content in accordance with convention. It features collections of letters written by BD Garga—published in magazines now defunct or unavailable for readership, unpublished pieces, correspondences with a wide range of filmmakers, archivists and acquaintances, as well as production stills from restored or rediscovered films. Built from disparate sources, the Garga Archives disrupts hierarchies of power extant in the field of historical documentation by making these materials easily available on an open-access platform, while attributing equal relevance to the otherwise illegitimate artefacts of myth, folklore and fringe data as constituting film cultures. Meant to resemble a detective investigation, information is treated as clues to a larger picture, initiating the reader to an alternative exercise in archival perusal. In the following conversation, Malhotra talks about the indexical impulse for the archive and the catalytic functions of the arbitrary, the processual and the reflexive.

Gul Hamid and Sabita Devi in Chandragupta. (1934.)

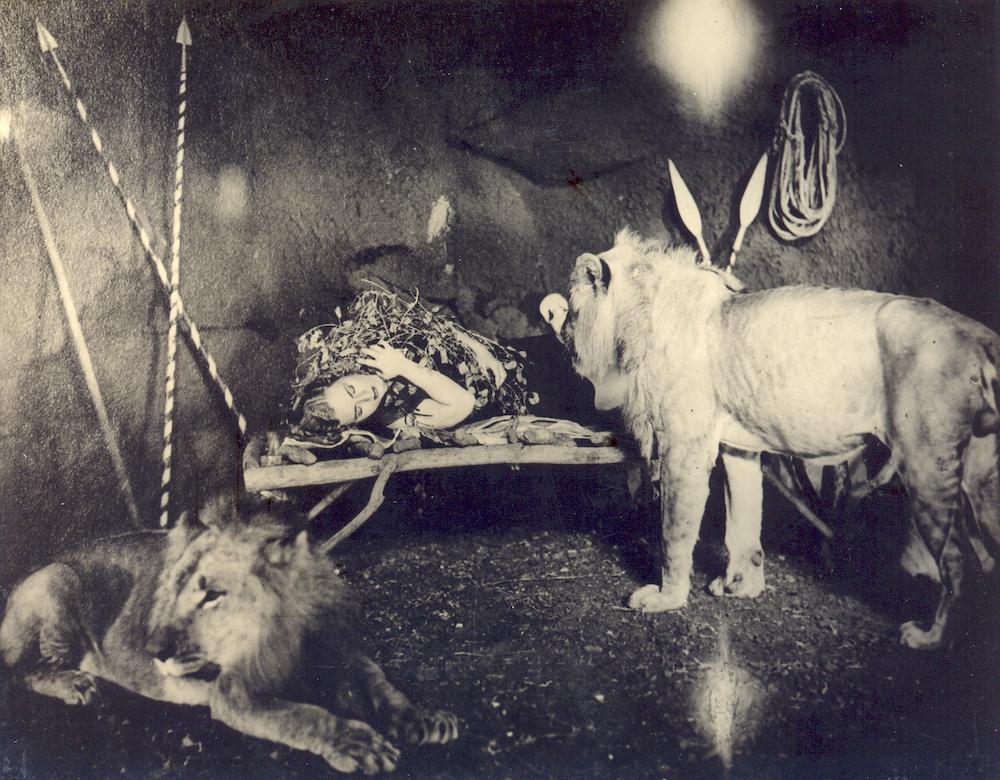

Still from Jungle Princess. (1942.)

Najrin Islam (NI): The indexical strategy for the digital archive is quite different from a traditional film repository. Could you speak about your editorial choices?

Anuj Malhotra (AM): We tried to imagine the exercise of building this archive in purely cartographic terms. This is an ambition that has now begun to take literal shape with The Mapmaker from Baghdad, an archival project we are working on as a sequel to The Reanimated Corpse, a game developed under the aegis of Five Million Incidents. If the traditional archive is a contoured enclosure with a strict geometry delineating its chief, material constituents through neat sections, we wanted to offer an alternative layout that is liquid, formless and exists without definition―an archive without walls. Secondly, our purpose was—and has been with almost all of our activities as a collective—to diffuse the normative authority invested in the figure of the contemporary curator. In the fields of preservation and exhibition, the archivist assumes an inordinate amount of power to determine value and to institute, as well as present, the canon. The history of remembrance conceals in its shadow the history of forgetting—a pending acknowledgement that should result in greater meditation within the field of archival studies on questions of the inclusion and exclusion of power (which consequently determines access) and the natural, political fallout of the schema.

A combination of these two aims helped us determine the publication schedule for the archives, wherein the content would be demarcated broadly into the sections “Writings” and “Correspondences,” while their respective constituents would sprout randomly without an apparent design or order. At the end of the exercise, the reader/visitor would be able to discern an impression of the body of work—in tandem with our intent to have it exist as an incomplete repository; an archive in the present-continuous, real-time process of becoming.

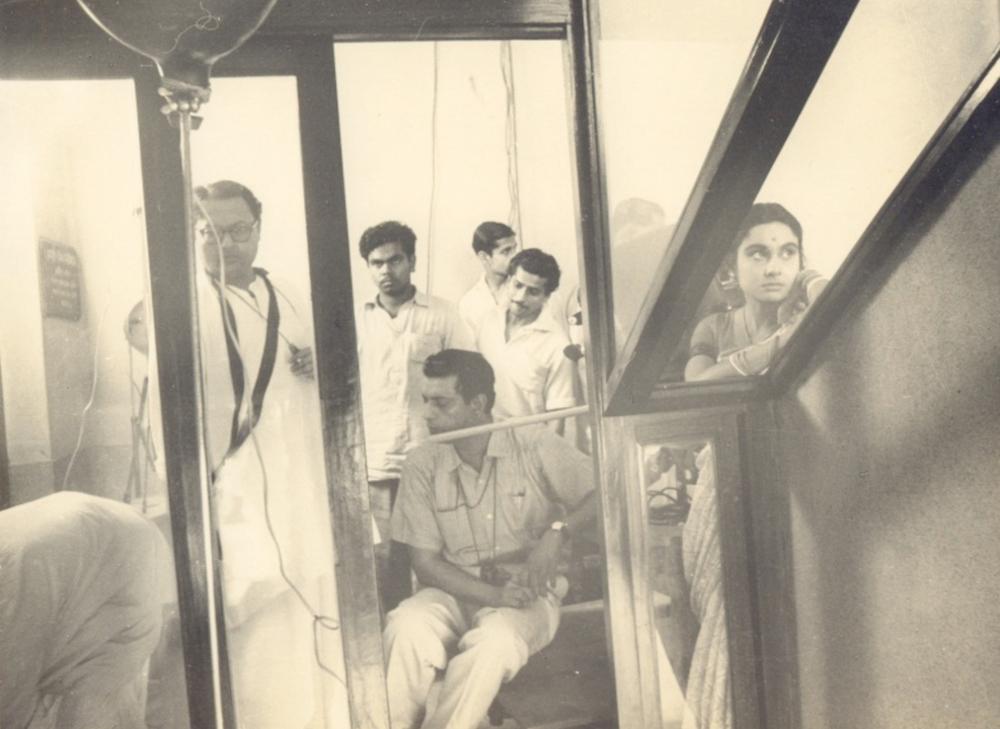

Satyajit Ray and his crew on location, shooting Mahanagar. (1963.)

Still from Pyaasa. (1957.)

NI: You mention on the website that the “…archive lays no claim to absolute authority” over the resources. In attempting to narrativise history and invite the public into its construction, how do you look at questions of ownership?

AM: During my attendance at the prestigious Collegium as part of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in 2017, I realised the obvious—that most archival models of preservation are large-scale, near-homogenised and rendered through an ultra-scientific, super-empirical, Eurocentric philosophy. This yields a model of remembrance that embraces the investigative tendencies of the traditional detective, but without their poetic lament or commentary. Film history then begins to resemble a directory of strictly indexed entries, which cultivates a process of canon-formation laden with elitism and a fundamental essentialism—determined by a small, privileged group with access to the necessary resources. This is evidenced in the set of mandated guidelines that are circulated through various film preservation and restoration workshops: the films need a vault (preferably underground) that is well-sealed, air-conditioned, free of moisture and heat, and maintained through the year. The subtext of this imperative is that a combination of these conditions is possible only in and for a few countries, which are based out of Western Europe or in North America.

In light of the knowledge that the actual material (the films themselves) has not survived in many parts of the world, a question arises: how do countries without adequate facilities, i.e., without the vaults or individuals to personnel them, preserve their films? And more significantly, how do countries where the films themselves are now lost remember them? In essence, how does one remember what modes of memorialisation exist, other than the ones prescribed by the centre? Can countries cultivate indigenous models of preservation that are customised to the realities of their own contexts? These questions provoked us, as a collective, into an imagination of film history as an exercise that does not rely on actual, present material, but transmits through oral forms that emerge instead from an absence: rumours, tall-tales, urban legends, conspiracy theories, grandmothers’ stories and neighbourhood gossip. This can allow film history to exist—not apart from, but amid the public—as shared consciousness, social heirloom, or folklore. The intention is to transfer control and ownership of the archive from a designated curator-figure to the people-at-large. In countries without the films and the archives to hold them (for instance, India, Iran, Mexico, or Sudan), film history is then preserved not as an inert sentence-case noun severed from the functions of its society, but as a living, vital organism that is present in the market, down the street, around the bend, by the red light and across it.

Still from Kalpana of Uday Shankar dancing. (1948.)

Himansu Rai and Seeta Devi in Light of Asia. (1925.)

NI: How do you look at creating a picture of the film culture of an era through one person’s memorabilia? What trajectories did this storytelling take for you as a curator?

AM: The archive identifies itself as a record of the life and work of BD Garga. This is not different from the subtitle that The Reanimated Corpse uses to declare itself to the world, which is: “The Animated Diaries of Rafique Baghdadi (sic).” The importance of subjectivities—and through them, of personal memory, biases, or limitations—in the process of archive-formation is essential to us since it must exist—as all film writing or thought on film should—from within the intersection of the anecdotal and the official. In each case, the purpose of the induced subjectivity is different—while Garga was a real-life figure, Baghdadi may or may not have actually ever existed. In the case of the Garga Archives therefore, we wanted to present the figure of BD Garga as a Zelig-like figure who happens to be present—intentionally but also by chance—at the site of some of the most significant zeitgeists in the history of cinema. He hobnobs or collaborates with, interviews or observes the primary figures of the French New Wave, technicians at the Mosfilm Studio, Jawaharlal Nehru and his Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, pioneers of Indian silent film, the chief instigators of Indian Parallel Cinema, the movers-and-shakers of film society movements from around the world, and more. We wanted to establish him within our narrative as a node where these individuals, institutions, movements and eras meet. This also accounts for the seemingly random order in which the contents of the archive are organised. They are to be experienced, after all, as BD Garga himself would have—as stimuli scattered in a sea of temporality with no intrinsic order or meaning; in short, as life itself.

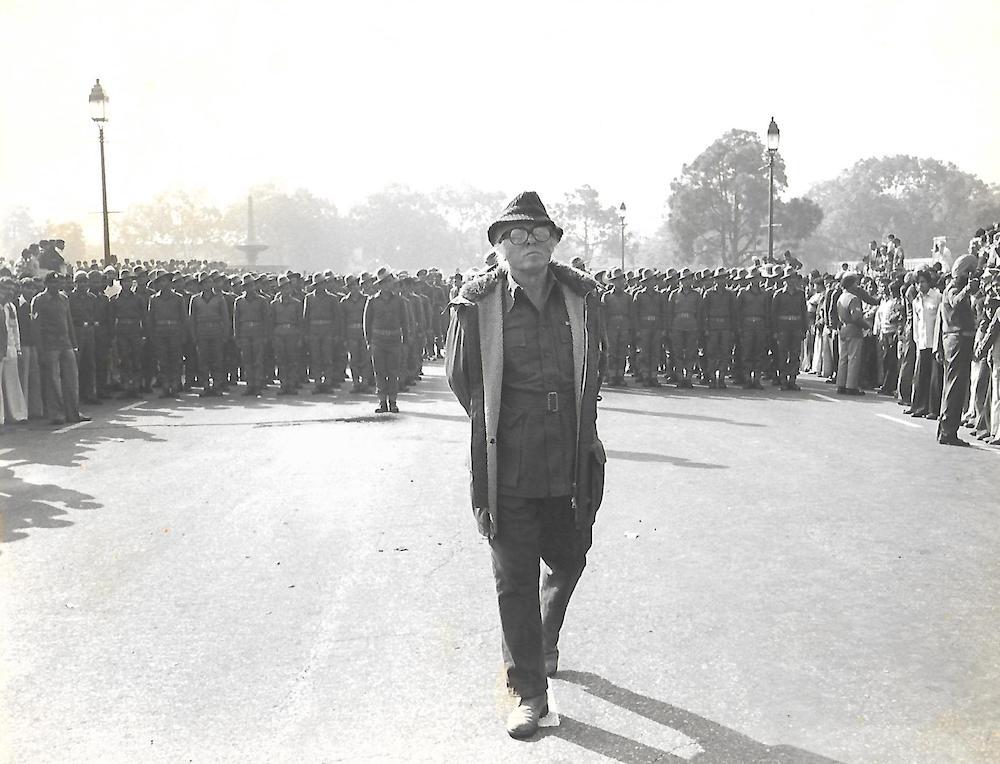

Richard Attenborough surveying the funeral scene for Gandhi. (1982.)

All images courtesy of Donabelle Garga and the Garga Archives.