Conforming Vision: The Stereograph in Colonial India

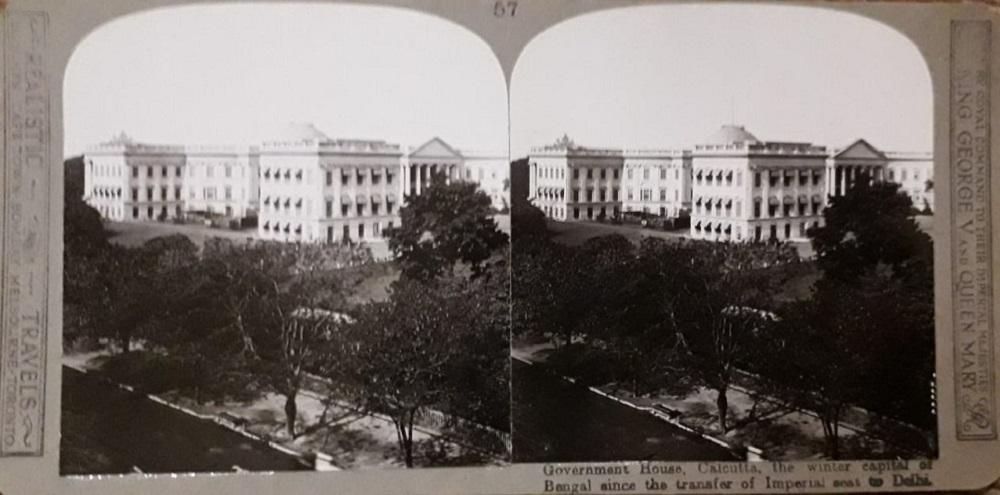

A stereograph of Kolkata’s Government House, described in the caption as “…the winter capital of Bengal since the transfer of Imperial seat to Delhi.” Printed vertically on the left side: “Realistic Travels: London–Cape Town–Bombay–Melbourne–Toronto”; right side: “By Royal Command to their Imperial Majesties King George V and Queen Mary.” (From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)

In colonial South Asia, the stereoscopic photograph (or stereograph) was frequently produced and widely disseminated to encourage cultures of travelling. It also enabled the development of leisurely interest in the flora, fauna, the people of India as well as the architecture and spaces created in the colonies by the British Raj. A stereograph consisted of a pair of images mounted side-by-side and fixed on a board. The twinned images were most likely photographs or photomechanical prints that described the same view through slightly different angles. These were meant to be presented under the instrument of the stereoscope—so that the illusion of a three-dimensional image may be created in the viewer’s mind. The tiny swerves of angularity, paired together, helped to create this effect of 3D vision. In the nineteenth-century, stereoscopic cameras that employed two lenses were introduced. These could take two images together, cutting down exposure time and allowing for movements without blurring.

Stereographs were largely produced by travel companies and stereographic firms like Underwood and Underwood among others. The series featured in this post were produced by Realistic Travels, founded by H.D. Girdwood. William Darrah, in his book The World of Stereographs, called it “…the most successful British stereo publisher in the twentieth century.”

For those looking to re-create the ways in which the travellers of the past saw these images, James Ricalton’s book India Through the Stereoscope offers an illustration. It remains a typically colonial text as discourses of travel, pleasure, leisure and the pre-figuration of landscapes were inevitably underpinned by instincts shaped by imperialism. This does not suggest a neat method of othering or exoticisation, however. Most of his introduction to the book is a lush rhapsody about the multifaceted and impossibly varied wonder that was colonial India. But as he is keen to emphasise, the inhabitants were not complete strangers but merely long-lost relatives who—if the mechanisms of English progress went well and unresisted—may one day be admitted back into the family proper: “We shall learn how much England has done to improve the condition of this oriental world of many races, tribes, languages and religions. We shall be the western descendants meeting the eastern descendants of a common, but remote ancestry—the Aryans.”

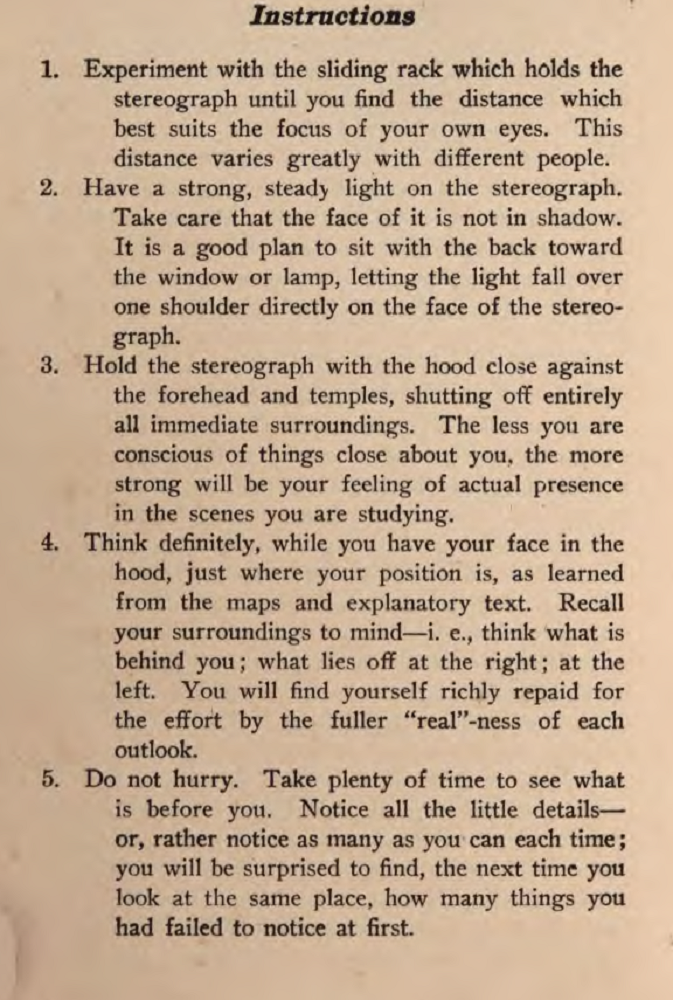

Ricalton’s book came with a set of instructions for the casual reader. These paint a description of the bodily performance that was necessary to immerse the reader into a strong sense of being actually present in those scenes, while shutting out their own surroundings. (In India Through the Stereoscope. By James Ricalton. New York: Underwood and Underwood, 1900. Source: Archive.org.)

A stereograph of the Calcutta High Court that was built after 1857. Caption on lower right corner: “The magnificent High Courts, resembling the Town Hall of Upres (sic), Calcutta.” (Grey [Slightly] Curved Card Mount with Round-Corner Images. From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)

The idea of this mythic commonality pressed itself into the cultures by which these images became legible to the public back in England or Europe. Consider the stereograph above of the “Magnificent High Courts” built in Kolkata after the British decided to set up their own colonial legal system post-1857. Designed by Walter L.B. Granville, who worked as a consulting architect with the Government of India at the time, it was made to look like the Cloth Hall in the Belgian town of Ieper. As prospective viewers peered into the deep surface of this stereograph, the space was made more homelike for their interest and enticement, activated by the superficial similarity of the aesthetic style (for that building). These immersive images were meant to push these travellers into recognising the space of the colony as relatable in more ways rather than simply as “odd”, “exotic” or irredeemably “different.” Within such a view of things, Ricalton’s project of difference and sameness, an anxious, unstable regime of mimesis, takes root so that an entire technology of seeing and performance can be appended to secure the authority of the colonial vision. These technologies inevitably included maps, compasses and diagrams—some of the basic tools of colonial governance:

“A mistaken direction in travel often results disastrously… so the stereo-itinerant may be twenty-five miles from topographic truth and accuracy, unless he conforms his vision, and adjusts his position, to the points of the compass. To enable him to do this, an excellent system of patent map diagrams… accompanies this book. With this brief foreword, we are ready to go over broad seas to the land of theosophy, the birth-place of religions, the home of the magician, the land where fair women are hidden from view, the land which, as I hope we shall learn on our journey, surpasses all other parts of the world in both natural and artificial wonders.”

And thus, the modern traveller, the “stereo-itinerant” of the broad seas was born.

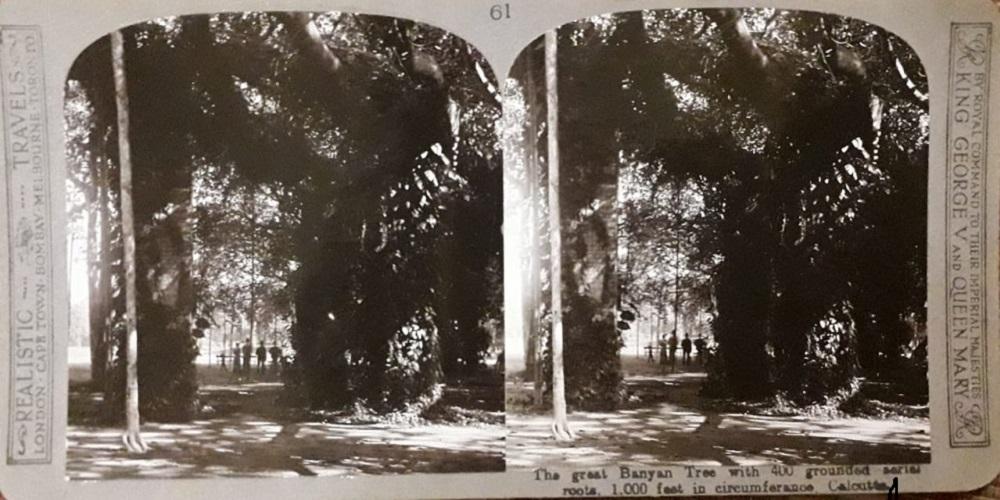

A stereograph taken at the Botanical Gardens, Kolkata. Caption on the lower right corner: “The great Banyan Tree with 400 grounded aerial roots, 1000 feet in circumference, Calcutta.” Ricalton saw these images as possessing a poetic, creative power over simply coercive regimes being enacted or transacted. As he writes, “…there is often a witchery and charm in stereoscopic scenes not found in the real presence of places and things.” (Grey [Slightly] Curved Card Mount with Round-Corner Images. From the private collection of Kazi Anirban.)