Photography as a Fine Art: Experiments with the New Medium in British India

At the inaugural meeting of the Photographic Society of Bombay in October 1854, its first president Captain Harry Barr of the eighth Bombay Native Infantry addressed his audience with the following proclamation: “Where I would ask, can that art (photography) be more advantageously studied than under the sunny skies of Ind?” Barr’s rhetorical question foregrounds the unique, even “advantageous,” connection between the Indian landscape and photographic practice in nineteenth-century British India. It also brings attention to the global imperial networks through which photography was promulgated across the world and how that subtly decentred Euro-Western authority over modern visual technologies.

Government House, Kolkata. (Photograph by Samuel Bourne. Kolkata, 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Around the same time that pioneer photography enthusiasts like Barr were contemplating the possibilities of this new medium in British India, a larger debate was taking shape in Europe. The photographic camera had caused an apparent collapse of art and industry by producing a stark likeness of its subjects through the play of light and technical apparatus as opposed to artistic skills and sheer imagination employed by painters and sculptors. The invention of photography thus triggered a crisis among the pre-existing and dominant visual regimes. It had a polarising effect on Western scholars and thinkers of the period where some lamented the loss of the aura that surrounded artworks and others celebrated the empirical visions generated by this machine.

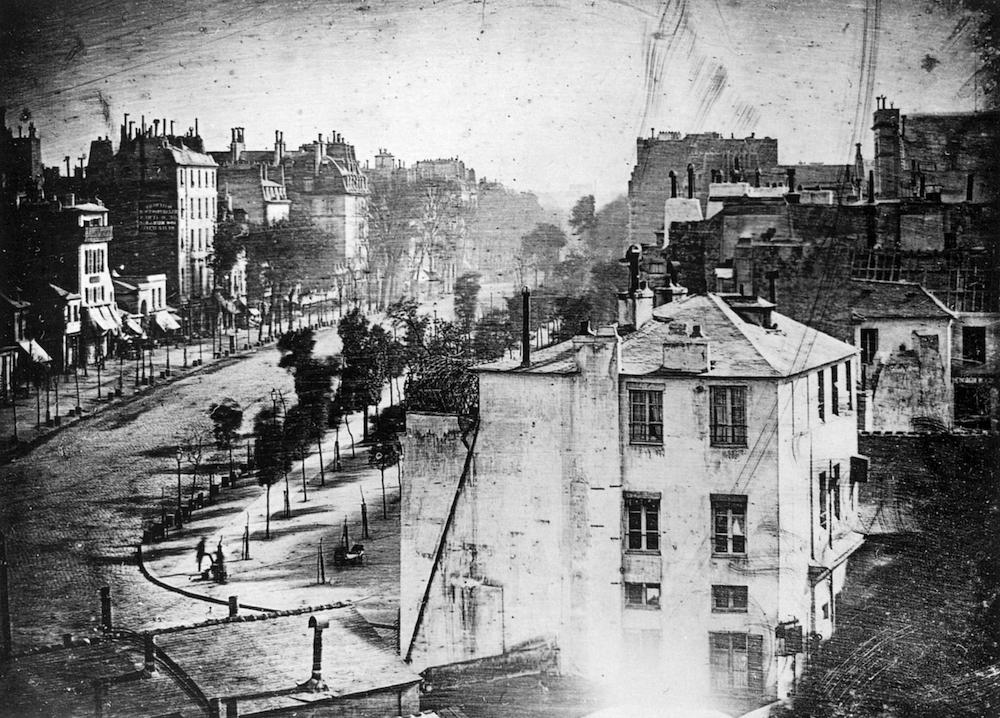

One of the first photographs ever taken by the pioneer of the photographic camera, Louis Daguerre. (Photograph by Louis Daguerre. Paris, 1838. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

While opinions in Europe were mostly divided on the consequent visual practices that emerged alongside the camera and whether they could be called “art” at all, there was no such dubious ascription to the status of photography in the colonial Indian milieu. British photographer Samuel Bourne, famous for his pioneering mid-nineteenth-century photographs of the Indian subcontinent, noted in a journal article in 1864:

“Unlike the treatment which photography received last year at the hands of the Commissioners in London, it is here (in India) classified as one of the fine arts. Are we then more enlightened, or simply more just unprejudiced in this land of rising British entrepreneurship than the would-be patrons of art in professedly free but somewhat clique-ridden England?"

Photograph of Tolly's Nullah or Adi Ganga near Kalighat. (Photograph by Samuel Bourne. Kolkata, 1860s. From the Series Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

The collective “we” in Bourne’s prose may have referred to Britons living in colonial India and a handful of princely elites that had access to photographic technology at the time. Nevertheless, it is important to note how Bourne characterises photographic practice in “this land” to be markedly different from its iteration in “clique-ridden England.” His appraisal reflects the centrality of the Indian subcontinent as a (colonial) site of technical innovation and commerce—a workshop/zone of experimentation. As photography simultaneously proliferated around the globe, photographers at the time acknowledged that the approaches towards photography that were prevalent in the Indian subcontinent were strictly not a case of supplanting or derivation from European knowledge systems.

Portrait of Jaswant Singh II of Jodhpur serves as an example of painting over a photograph. (Photographer Unknown, Overpainted by Shivalal. Rajasthan, 1873–96. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

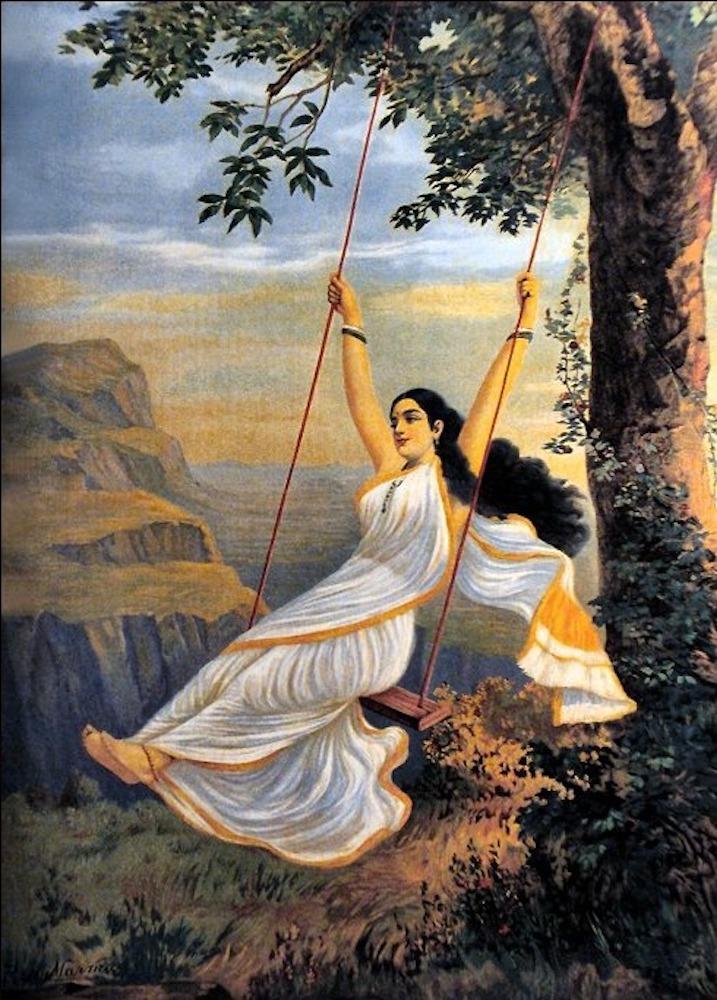

In fact, as visual anthropologist Christopher Pinney has argued photography was quickly assimilated within the multitude of visual cultural practices already prolific in India. The loss of the aura of the art object ascribed to the mechanically reproducible photographic image associated (and mourned over) with the emergence of photography in the West, was not as palpable in India. Instead, there was an aesthetic intimacy (as well as continuity) that was at work between photography, lithography and painting. Painted photographs—a genre that thrived in mid-nineteenth-century India—conjoined photography and painting with exceptional ease. Painters and artists patronised in princely courts in particular used their skills and training in miniature art to embellish black and white photographic prints in colourful ways. Similarly, painter Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906) used photographic techniques to develop lithographic and oleographic prints that became immensely popular within an emergent vernacular visual culture in British India.

Mohini. (Oleograph by Raja Ravi Varma. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

You can read more about photography in colonial India here and here.