Revisiting the Role of Women in Photography: The New Woman Behind the Camera

Cover of the exhibition catalogue. (Photograph by Alma Lavenson. In The New Woman Behind the Camera. Edited with text by Andrea Nelson. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2020.)

The New Woman Behind the Camera is a travelling exhibition set to open at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in July 2021, followed by a showing at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington in October. Featuring more than 120 photographers from over 20 countries, this groundbreaking exhibition explores how women emerged as a driving force in modern photography from the 1920s to the 1950s, bringing their own perspectives to artistic experimentation, studio portraiture, fashion and advertising work, scenes of urban life, ethnography and photojournalism. This revisionist attempt at recognising the role of women in photography and within the space of a museum acknowledges—in its curatorial note as a part of the catalogue—how the term “woman photographer” attempts to tie together a largely heterogeneous group of individuals who would not necessarily choose to identify primarily with this category. Yet, it is a useful term to explore and align with the identity of the “New Woman.” As Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art said in a press release on their website: "This innovative exhibition reevaluates the history of modern photography through the lens of the New Woman, a feminist ideal that emerged at the end of the 19th century and spread globally during the first half of the 20th century."

Left: Niu Weiyu with Camera. (Photograph by Shu Ye. China, c.1960. In The New Woman Behind the Camera. Edited with text by Andrea Nelson. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2020.)

Right: Masker Self-Portrait (No.16). (Photograph by Gertrud Arndt. Germany, 1930. In The New Woman Behind the Camera. Edited with text by Andrea Nelson. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2020.)

Unsurprisingly, despite the attempt to be an international survey of these women practitioners, this exhibition is bogged down by a predominance of Western photographers, as is evidenced through the detailed index listing all of the photographers included in the exhibition. In this manner, it ends up reinscribing a lot of familiar names. This is so while women from other parts of the world continue to fight for representation in a patriarchal system as well as against persistent racial and ethnic inequality.

(Photograph by Homai Vyarawalla. Mumbai, 1940s. Image courtesy of Homai Vyarawalla Archive/ The Alkazi Collection of Photography.)

On the question of invisibility, photo historian and curator Sabeena Gadihoke writes in “The Home and Beyond—Domestic and Amateur Photography by Women in India (1930–1960)”:

“Perhaps one reason for this invisibility is the way in which notions of the professional have been defined, which made it impossible for them to be part of this history. Most women in the past would have photographed in spaces that were not as visible as those in which male photographers might work. They also probably catered to needs within photography that were different. It is for these reasons that dichotomies between professional, amateur and domestic photography need to be challenged in order to reconstruct a history of the woman photographer.”

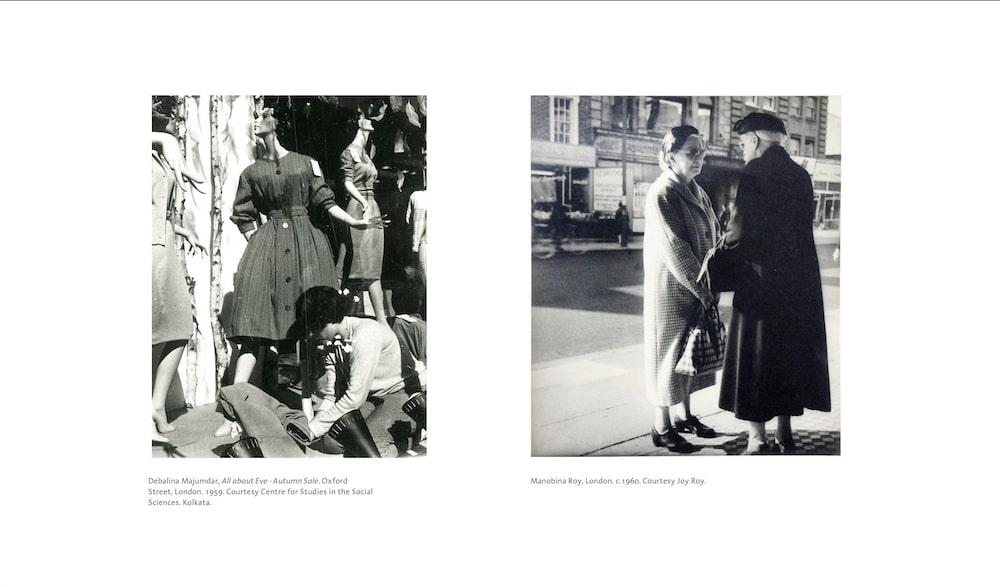

It is these worlds that an exhibition like The New Woman Behind the Camera ends up overlooking. In its search for women photographers within the artificial confines of the professional; the amateur photographers and the enthusiasts get left behind. Thereby forcing names such as the Bengali twin sisters Debalina Majumdar and Manobina Roy—whose practices exemplify an amateur tradition of photography that went beyond domestic spaces—and countless others out of such photographic histories.

Left: All About Eve—Autumn Sale, Oxford Street. (Photograph by Debalina Majumdar. London, 1959. Image courtesy of Centre for Studies in the Social Sciences, Kolkata and PIX.)

Right: Two women on a London street. (Photograph by Manobina Roy. London, c.1960. Image courtesy of Joy Roy and PIX.)

However flawed the exhibition may be, this attempt must not be dismissed. Following a long history of obscuration, any opportunity for a woman to be seen and heard must be repeated again and again. As all good surveys go, the exhibition highlights not just those included but those who continue to remain absent.

To read more about women in photography in India in the 1930s–50s, click here and here.