Breaking Stillness: An Interview with Susanta Mandal

What happens to still images within kinetic infrastructures? What is the relationship between image, movement and transience? And what are some of the ways in which we can rethink the idea of memory, history and the collective in contemporary art-making? Multimedia artist Susanta Mandal speaks to Ketaki Varma about some of these ideas. He elaborates on the role of the image in his practice, working with ephemerality, and his recent curatorial work Erasure at Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi.

Susanta Mandal. (Photograph by Kojagari. 2019.)

Ketaki Varma (KV): Much of your work employs kinetic mechanisms to create multimedia installations from images and quotidian materials, bringing together various technologies to produce a multisensory experience for the viewer. As an image-maker, what do you think happens to the still image within this framework of movement, when one sees the image perform, as it were?

Susanta Mandal (SM): To me, a still image is a frozen moment from the whole event or an episode. There are images before and after any particular image. When we look at the image, it drags us in, into the particular space and time too. So if I broke its stillness to recreate many more sequences, how does it appear to our eyes? Does it connect with the images; the way our memory holds onto and remembers a particular incident?

KV: One notices that ephemerality is at the centre of a lot of your work—the use of light, shadows, bubbles, transient images, memories of people and places. Could you elaborate on this?

SM: When I was a student at the College of Art (Kolkata), we often discussed the fact that a work of art has to be made in a lasting medium. So, we used to translate our thoughts mainly via conventional or durable mediums. Later, I realised that these were not enough to deliver my thoughts. I started looking for other possibilities. (2005 onwards) I got hooked to the idea of fragility, uncertainty and their tangible experiences. How could I unfold these aspects in my works? I started experimenting, therefore, with foams/ bubbles made with simple soap solutions.

During this time, I made a series called It Doesn’t Bite. In most of the works (in the series), some parts are always impermanent—the bubbles create a fragile structure that lasts for a few seconds and then they burst one by one. It is a performance where the super soft motion of bubbles breathes on solid steel. Capturing bubbles or clouds, or holding them in a cage is physically impossible. The apparent playfulness in the structure comes to an end with an unknown emptiness.

Left: It Doesn’t Bite-1. (Susanta Mandal. Bengaluru, 2007. Steel Structure, Black Granite, Glass, Air Pump, Soap Solution and Timer. 26 × 28 × 20 inches. Image courtesy of GALLERYSKE, Bengaluru.)

Right: It Doesn’t Bite-4. (Susanta Mandal. Bengaluru, 2007. Steel Structure, Black Granite, Glass, Air Pump, Soap Solution and Timer. 26 × 22 × 20 inches. Image courtesy of GALLERYSKE, Bengaluru.)

Left: It Doesn’t Bite-2. (Susanta Mandal. Bengaluru, 2007. Steel Structure, Black Granite, Glass, Air Pump, Soap Solution and Timer. 26 × 24 × 20 inches. Image courtesy of GALLERYSKE, Bengaluru.)

Right: It Doesn’t Bite-4. (Susanta Mandal. Bengaluru, 2007. Steel Structure, Black Granite, Glass, Air Pump, Soap Solution and Timer. Image courtesy of GALLERYSKE, Bengaluru.)

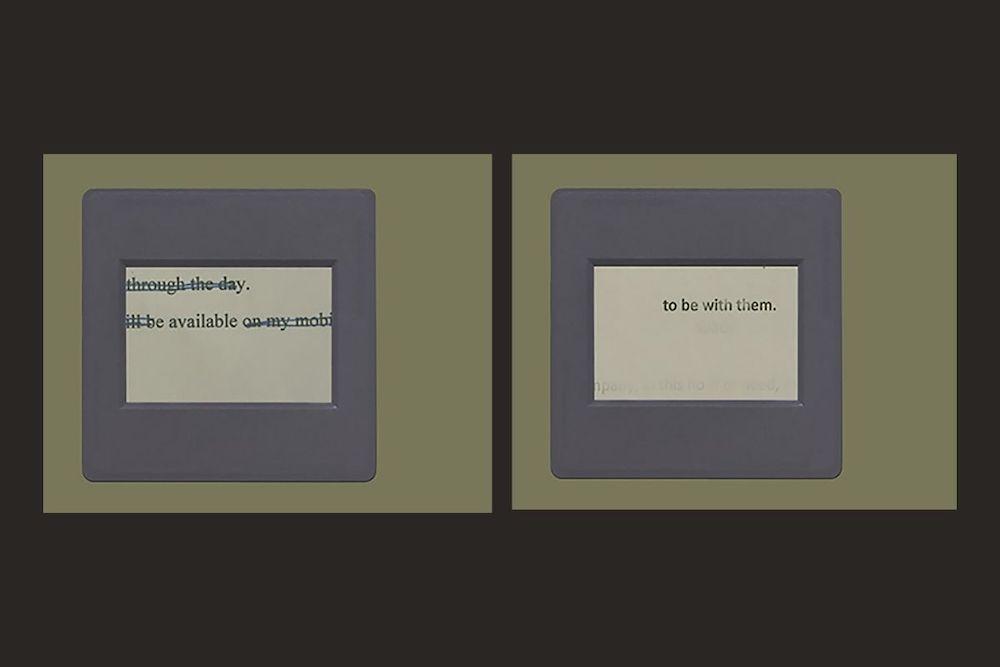

I began my experimentation with still images in 2010. For these works, I developed a few structures with lenses that were inspired by the magic lantern. The magic lantern was a fashionable projection device in the Victorian period that was made using simple mechanics, lens, kerosene lamp and hand-painted slides. I took the basics of the magic lantern and made sculptural works to see still images through this different approach. For instance, in Hard Copy-II, I played with still images through my kinetic structures. Here, I took absence as a metaphor: where two ordinary samples of “leave of absence” letters were picked up; reprinted on Photostat papers; then erased, faded, a few words cut out with ink pen to create many more fragments of the specific letters; and finally used as images in the form of slides. This might echo something very personal as well as impersonal. Here, the moving lenses created a slippery zone, such that the image acquired multiple dimensions and gave a different understanding of duration, space, perception and reality.

Left and right: Hard Copy. (Susanta Mandal. New Delhi, 2014. Steel Structure, Lenses, LEDs, Transparencies, 0.5 RPM Motor and Timer. Images courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.)

Left and right: Hard Copy. (Susanta Mandal. New Delhi, 2014. Steel Structure, Lenses, LEDs, Transparencies, 0.5 RPM Motor and Timer. Images courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.)

KV: Your recent curatorial project Erasure looked at the link between two kinds of erasure: those that inhabit history as a discipline, which has the ability to structure the past and rewrite it at will; and the pathology of dementia, a more individualised erasure that has to do with personal memories and modes of forgetting. Tell us about this project. How does your practice as an artist feed into your curatorial vision?

SM: When I was thinking about the show based on the idea of “erasure” and its multiple possibilities, I found it interesting to connect contrasting thoughts within the area of erasure. There were two main triggers that came to my mind: Firstly, in a page filled with diary entries by Clive Wearing, a British musician and composer—whose short-term memory was reduced to under twenty-seven seconds due to illness—the line “Now I am” is followed by crossed-out repeats. Here, time has lost meaning and the present is unhinged and floating without any context.

Secondly, is “historical erasure” used as a tool for controlling the masses? How does it blur collective memories? How do we fail to recall the most vivid losses or damages? Forcing collective dementia is quite an old practice. The removal of traces continues as an act, which has never stopped. A contrary, alternative history builds up on the margin—how does it speak, how do we read its silences, is it a work of fiction? Who will decide, for the sake of truth, which history is unbiased? The tragedy of Clive Wearing’s forgotten memory looms before us. And it leaves us asking questions about the voluntary and involuntary acts of erasure.

Installation View of Museum Piece #9 A(Politically Black) by Mithu Sen at Erasure. (New Delhi, 2021. Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.)

Installation View of Maraland by Sayantan Maitra Boka at Erasure. (New Delhi, 2021. Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.)

Often, in my own practice, similar kinds of thoughts have been woven with memory, absence and remembering. Thus I thought of asking a group of artists—those I admire for their distinct practices—to exchange ideas (with me) through an exhibition format. I wanted to consider a parallel thread where these practitioners from the fields of music, dance, medicine, theatre, architecture, education, etc., also contributed their thoughts and expressions on the theme of erasure. And I must say, every bit of this process was a wonderful journey for me.

Click here to watch the walk-through of the exhibition Erasure with Susanta Mandal.

All images courtesy of Susanta Mandal.