Nationalist Cinemas of Bangladesh: A Discussion on John W. Hood’s The Bleeding Lotus

In this continuing discussion on John W. Hood’s The Bleeding Lotus, we focus on how his analysis foregrounds some of the important themes in Bangladesh’s nationalist cinema. The problem of proximate living in conflict with communal living—which has always been a flashpoint for disharmony in South Asia—is explored through films like Tauquir Ahmed’s Joyjatra (The Victory Procession, 2004) and Tareque and Catherine Masud’s Noroshundor (The Barbershop, 2009). From before 1971 and after, the legacy of Urdu-speaking Muslims and their contentious place—as oppressed inhabitants who have been denied their citizenship rights or as “Razakars” who challenged the rights of Bengalis to separate themselves from Pakistan—in postcolonial Bangladesh remains a source of tension as well as potential reconciliation.

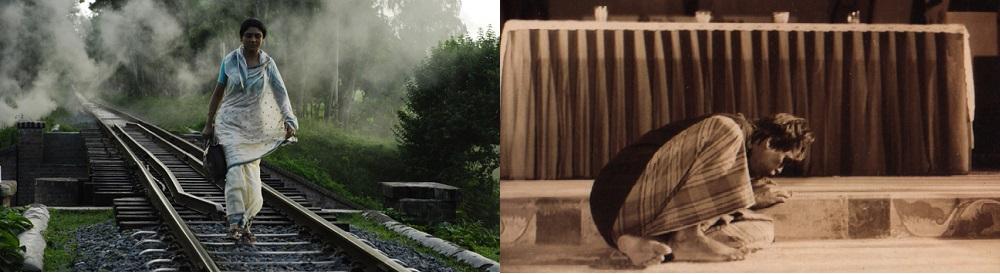

Stills from the films Guerilla (2011) and Ekattorer Jishu (Jesus of ’71, 1993). (Dir. Nasiruddin Yousuff. In The Bleeding Lotus. By John W. Hood. New Delhi: Palimpsest Publishing House, 2015. Images courtesy of Palimpsest Publishing House.)

As Hood suggests through his reading of films like Itihas Konya, Narir Katha (Women and War, 2000) and Morshedul Islam’s Khelaghar (Playhouse, 2006), the sexual exploitation and violence visited on women—conducted on a mass scale by the West Pakistani army and their collaborators during the struggle for Liberation in 1971—occupies a key traumatic centrepiece in the national cinemas of Bangladesh. These films have tried to adopt different points of view with regard to the theme. Some attempt to communicate the scale of the violence while others try to work around the limitations of archival documentation to make critical interventions into the reception and memorialisation of such sacrifices made by women.

Posters for the films Itihas Konya (Daughters of History, 2000) and Pita (The Father, 2013).

Within the scope of his theme, the author explores the subject at some length, moving to newer articulations of nationhood in films produced during the 1990s and the new millennium. These tend to work with new genres, styles and approaches to the seminal events of 1971. The films reflect on the complex historical processes that determine the formation of memories under the imperatives of nation-building—although with films like Pita (The Father, 2013), we are increasingly in the realm of popular melodrama (as the poster also indicates clearly), a staple form across subcontinental cinemas where sensationalism and romanticism take over the narration of the nation’s struggles against occupation.

Still from the film Rabeya. (Dir. Tanvir Mokammel. 2008.)

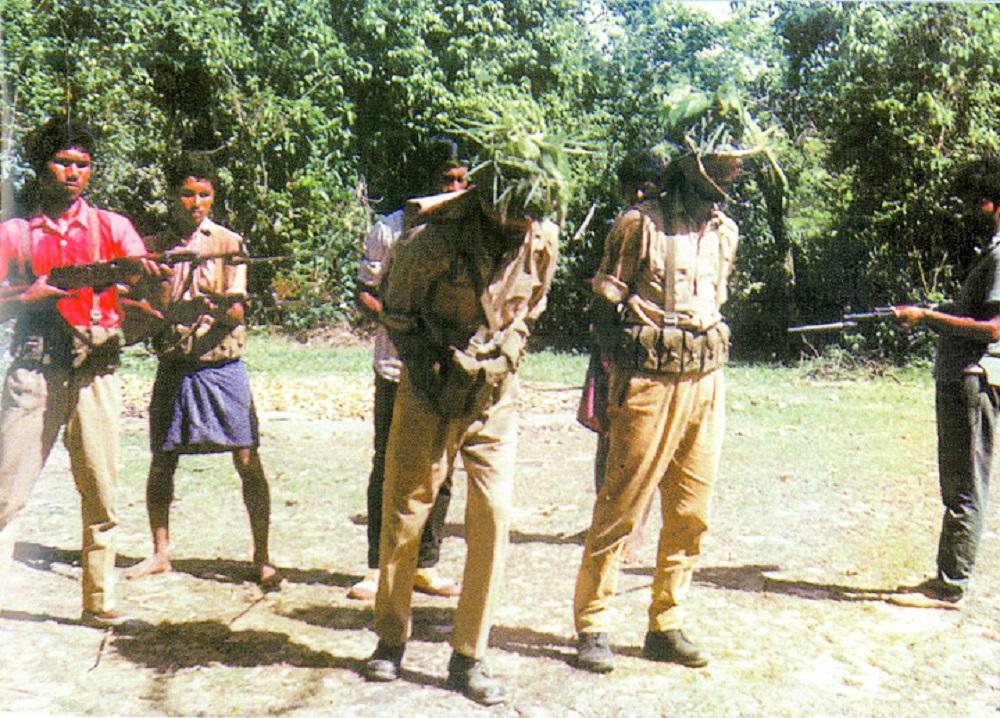

It is worth noting that the films of Ritwik Ghatak or Rajen Tarafdar, who mostly worked and lived in West Bengal but made films relating to the people and landscapes of East Pakistan and Bangladesh, are not discussed either. Realist dramas, documentaries and non-fiction films find prominence in this study, implying perhaps that these genres can give us more immediate access to the events, ideas and concepts that formed Bangladesh’s national imagination. Since the taxonomy begins after the events of 1971, other forms of potential national expression—through popular forms like the jatra cinema of Salahuddin Ahmed, made in the previous decade—are passed over too. Supplemented by a similar approach in the documentaries that he studies, and the occasional impulse toward uncritical summarising aside, the book is a useful introduction to the cinemas of Bangladesh.

Still from 1971 (Dir. Tanvir Mokammel. 2011.)