An Intimate Requiem: Alana Hunt Discusses Cups of nun chai

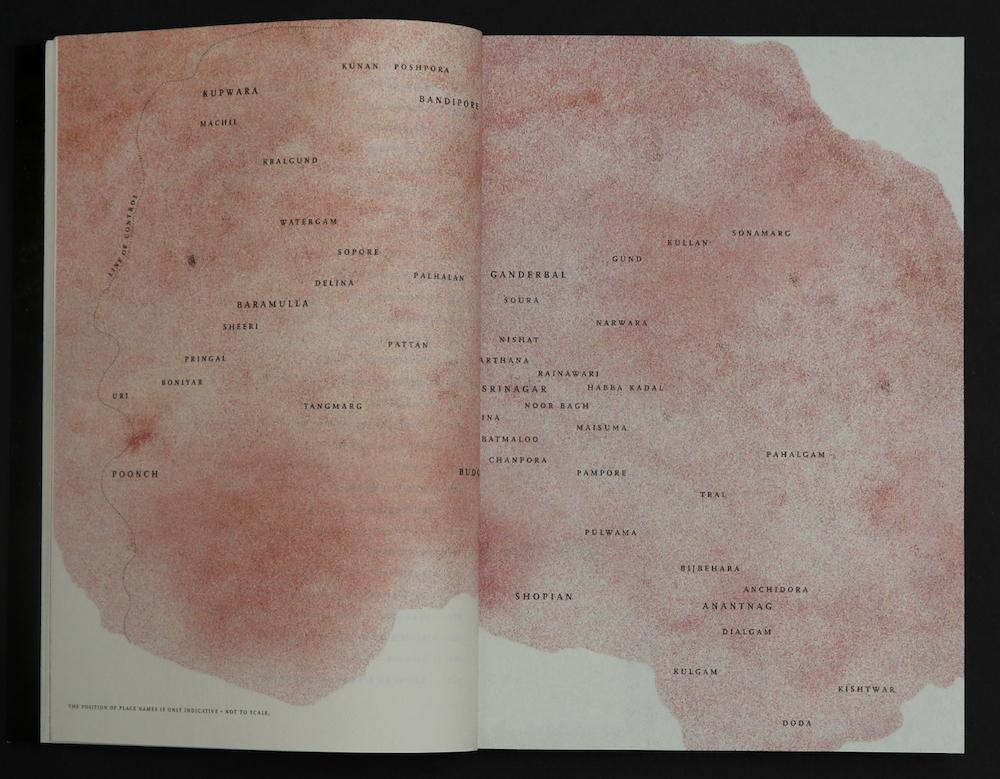

Australian artist and writer Alana Hunt’s decade-long iterative work Cups of nun chai searches for meaning in the face of the Indian state’s absurd brutality in Kashmir.

In this conversation with Senjuti Mukherjee, Hunt discusses the political events that led to this work, how she attempted to decentre herself by building a repository of diverse narratives of loss and resistance, and arrived at a metaphorical iconography that asks: “What is more persistent—life or siege?”

Senjuti Mukherjee (SM): You use the trope of conversation to unearth Kashmir's volatile present and past. How did you arrive at this particular interactive form as the mainstay of the book?

Alana Hunt (AH): Although Kashmir had been gradually seeping into my life through books, films and people I met; it was during intimate conversations over cups of nun chai inside Kashmiri homes that I came to encounter the place in a way that was tangible and hard to turn away from.

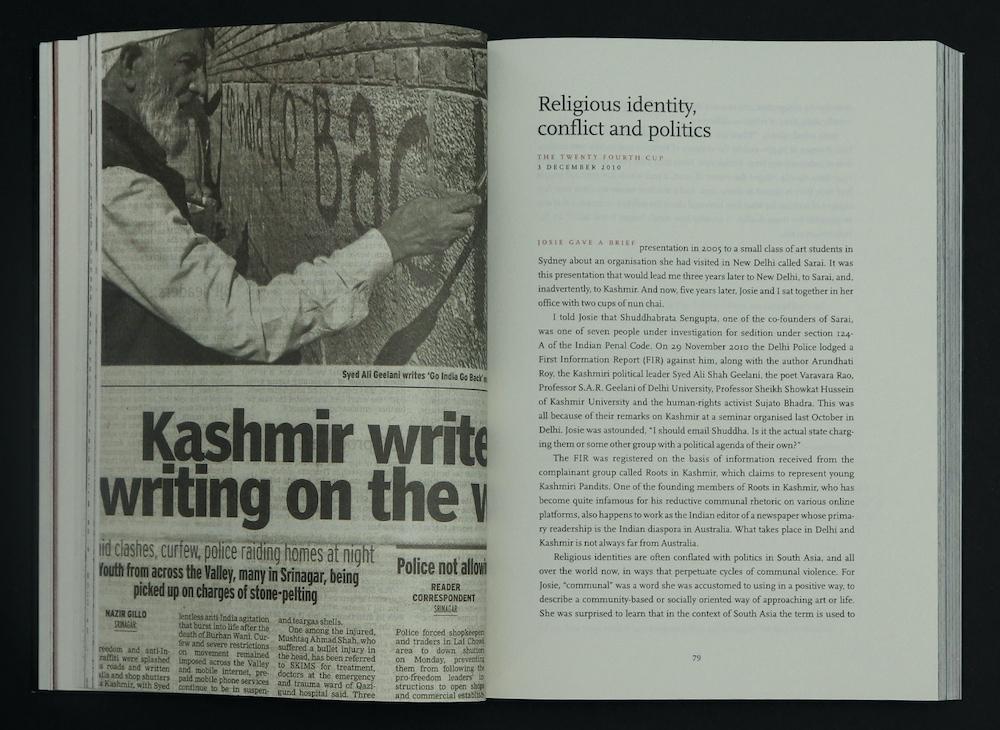

As the summer of 2010 unfolded, 118 people were killed by the state in almost as many days. There was an outpouring of powerful writing from Kashmir—much of which came from people of my generation. But it did not reach where I was in Australia, nor in many parts of the world, including India.

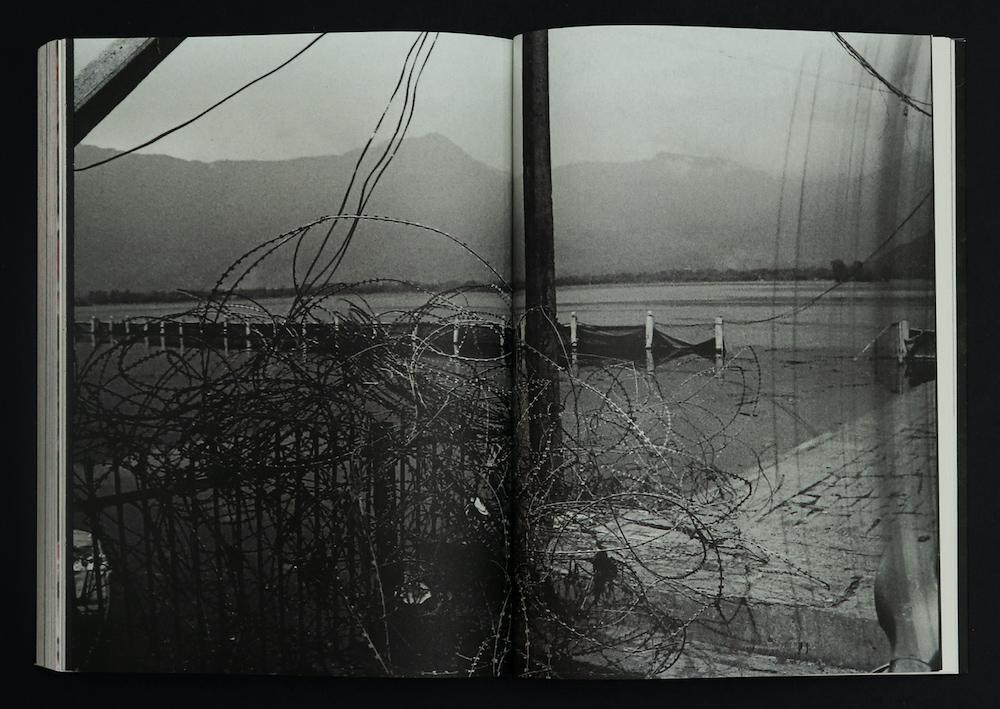

I wanted to bridge that by crafting an intimate requiem to this loss of life. One that moved against the normalisation of state violence, marked it and built a constellation of the world that surrounded it. I was conscious that the space of the home—where I had encountered Kashmir most vividly—was where this loss would be felt the most.

Cups of nun chai is a little beguiling, in the sense that I have used the convivial nature of tea to begin a series of conversations about some of the most intense forms of political oppression taking place today. Here, conversation emerges as a means of journeying deeper into a space that invites mutual exchange—a space that does not require experts, but allows for nuance, uncertainty and emotion. Conversation also crafts vast connections between people, places and moments otherwise isolated from one another. It is often in quietly spoken words that some of Kashmir’s greatest truths lie.

SM: This current phase of political resistance against the Indian state’s brutality in Kashmir started in the early 1990s; tell us a little bit about your involvement and response to the 2010 event and its location in the political history of the valley?

AH: I was travelling from Kashmir to Delhi by road in 2010 when Tufail Ahmad Mattoo, a seventeen-year-old heading home from tuitions was killed by a tear gas cannister that hit his head. When I reached Delhi, a friend came up to me—rather flustered—and told me about Mattoo’s death. At first, I could not understand her exasperation—many people had been killed in Kashmir when I had been there in the preceding months—then I caught myself and realised how quickly political violence becomes normalised in a place like Kashmir, even for me as a foreigner who was relatively new to the context.

A few weeks later I returned to Australia after almost three years. The violence in Kashmir continued as the state responded with extreme levels of repression to an outpouring of public mourning and protests that followed Mattoo’s killing. I had just begun to use social media and my newsfeed was full of Kashmiri friends recounting what was happening around them. As the death toll continued to rise, Australia barely took note. There was a gaping silence across the media. Cups of nun chai emerged as a means of moving against that creeping sense of normalisation.

I began to encounter Kashmir from 2008 onwards. This was a period in which some say Kashmiris were breaking the silence, and Kashmir was beginning to step out of the shadows. Many people of my generation were intensely committed to what they often described as the “power of the pen,” explained to me in contrast to the gun which a previous generation had taken up in the 1990s. But even then it was commonly said that if these voices are not heard, the gun will return. Now the line between the two seems less distinct.

SM: In the publication, the conversations switch between disciplinary boundaries—of social history, political journalism, literature and visual cultures—in a seamless fashion. Tell us about the necessity that you may have felt to explore multiple chronologies and subjectivities in order to archive the social and emotional life of a community that is completely absent or misrepresented in mainstream media and state narratives.

AH: The disciplinary spheres you mention are really things that influence me as an artist, things that form a part of my world. So, the way in which they enter the work was relatively intuitive.

I would not say I set out to “…archive the social and emotional life of a community”; I find “community” a really difficult word. Within the arts, as in many spheres of government, the term has been increasingly bureaucratised, encapsulating people with a vague, inaccurate sense of homogeneity, that does disservice to the diversity of lived experience.

My work responded to serious incidents happening in places and to people I had come to know and care for. There is a reciprocity within this. As much as the work is about Kashmir, it is also about India, with slices of Australia and other parts of the world.

Though my own views are no doubt present in the work, while making Cups of nun chai I felt a necessity to decentre myself—my view was not enough. This was achieved via dialogue. It felt more useful to make space for a multitude of subjectivities to galvanise around this work as a requiem, a process through which I was also learning. Of course, the work is centred on what was taking place in 2010, trying to hold onto some of the things that would otherwise evaporate with time—in a sense to archive the moment. But there is no way of properly understanding 2010 without the larger history of Kashmir. And this history—while unique—also resonates with other places in Asia, Australia and the world. So, as people I invited into the project began to encounter Kashmir, they inevitably made sense of it by drawing on their own experiences of colonisation, state violence and resistance in other parts of the world and periods of time.

SM: This body of work first appeared in a serialised form in the Srinagar-based newspaper Kashmir Reader. What was your experience working with press editors for this work? Besides, Kashmiri media has been severely censored over the years, what were the complexities of publishing your work within that context?

AH: Prior to the serialisation within Kashmir Reader, Cups of nun chai had accumulated progressively on the work’s website, and had appeared in a number of small exhibitions outside Kashmir. But it was important to me that the work also reached people within Kashmir. In terms of reaching audiences there, a conventional art exhibition was not possible, and likely to reach a very limited audience if it was. Additionally, I did not have the means to produce a book at that time, so the newspaper emerged as an ideal place to circulate the work to an audience within Kashmir in an everyday kind of way—an exhibition slipping within the folds of a newspaper.

At a more conceptual level, I wanted to juxtapose the memory of 2010 alongside the news of the day in order to draw connections between what might have shifted politically over time and what remained the same.

I did not want to burden the editors of Kashmir Reader with my own aesthetic demands, so I more or less went with the paper’s regular layout. The editors at the time pulled the titles from each of the texts. These so aptly conveyed the tone and content that we have retained them as the basis of the chapter headings in the book. A nice collaboration.

We began the serialisation in June 2016, on the anniversary of Tufail Ahmad Mattoo’s death. A month later, Burhan Wani was killed. The mass public mourning, protests and state repression meant that 2016 began to connect with the memory of 2010 well beyond my work. Amid huge crackdowns on civil society there was immense pressure on the media fraternity: newspapers were stopped from going to print, internet was regularly cut and journalists’ movements curtailed. This eventually led to the unprecedented banning of Kashmir Reader, cutting off the serialisation of Cups of nun chai mid-way.

I was certain the newspaper would not return to print, and even if it did, I assumed it would no longer carry Cups of nun chai. When after three months the ban was lifted, the editors were keen to continue from their very first issue, and to complete the serialisation of my work before they moved on from the organisation. Their commitment to serialising Cups of nun chai was quite phenomenal. Probably one of the best forms of “feedback” I have ever received.

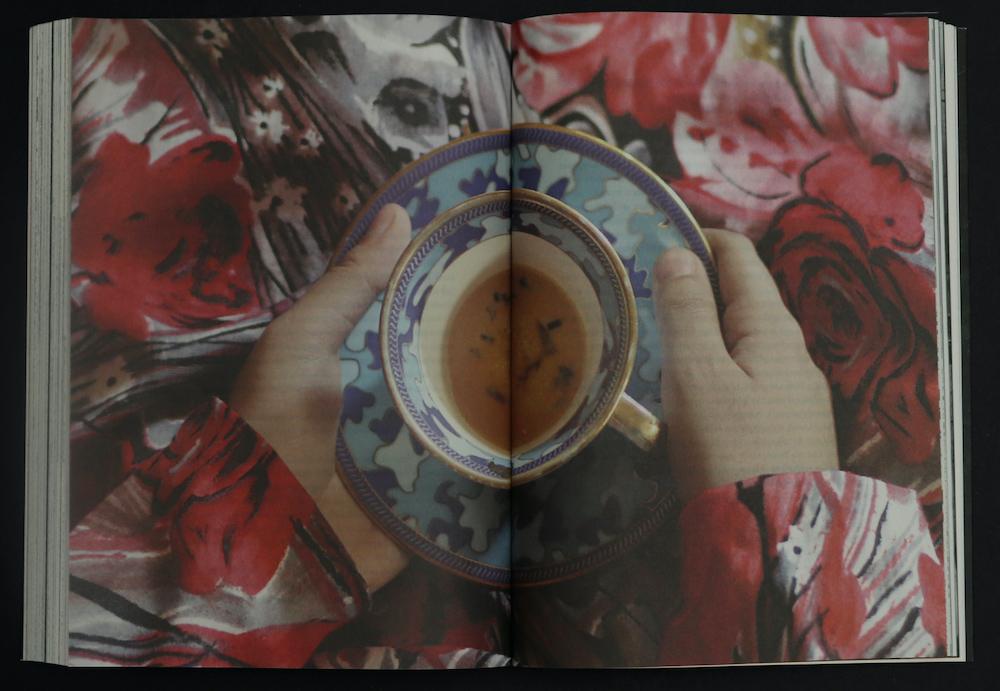

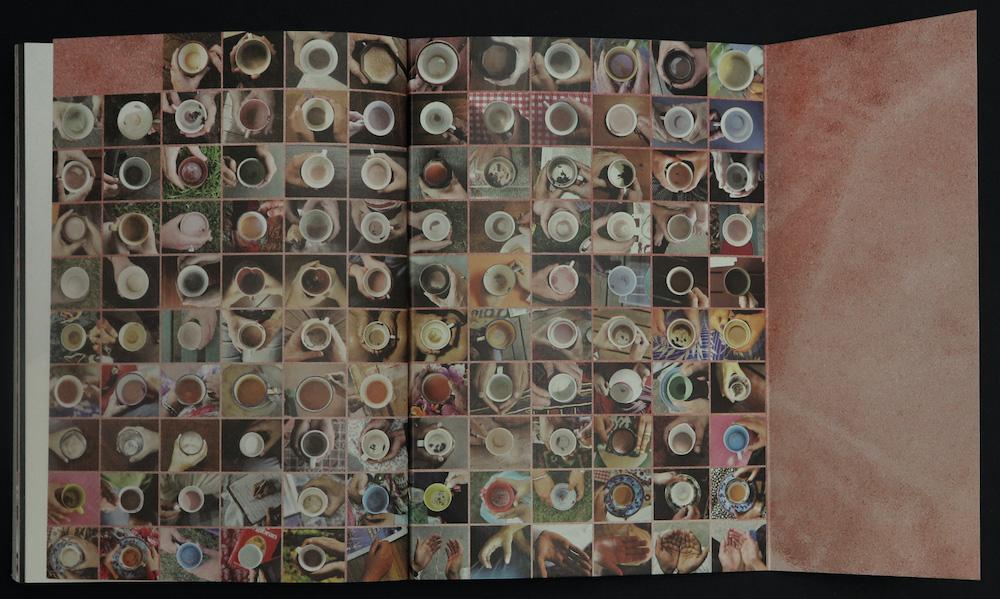

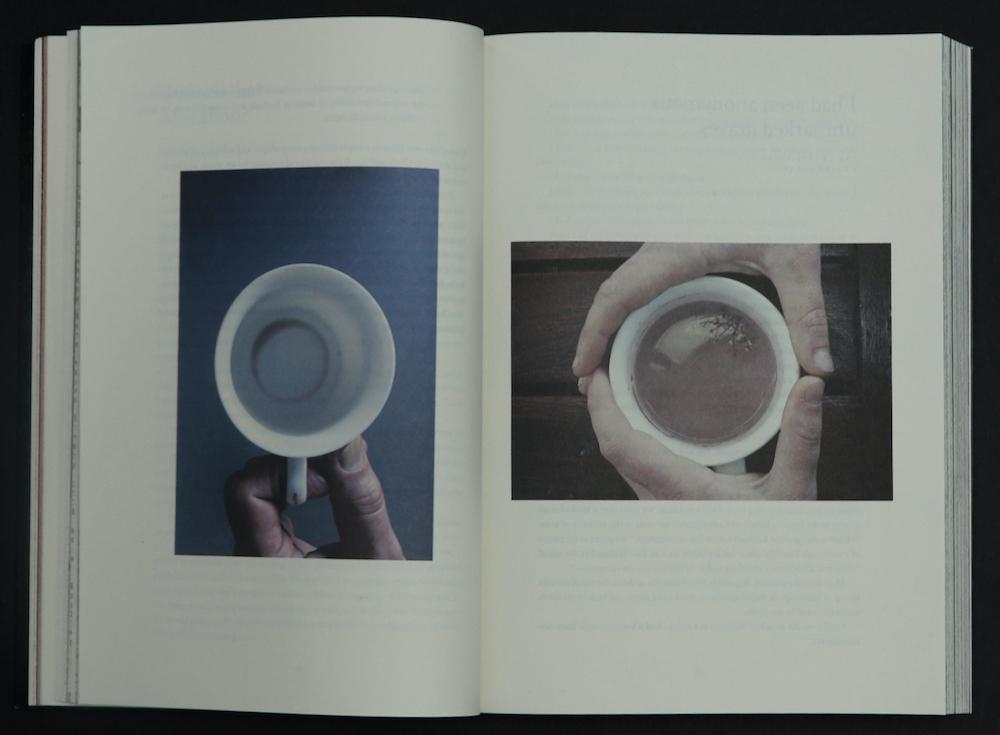

SM: Nun chai, the samovar, the cups without handles are intrinsic to the social and visual life of Kashmir. The images show hands holding the cups and the series ends with pictures of hands in a call to prayer and during Ramadan, a pair of palms cupped without the vessel. What lead you to this unique metaphorical iconography in the book?

AH: The visual language of the work emerged in response to the standard binary of beauty and violence—or even the beautification of violence—which dominates representations of Kashmir. The hands holding each cup of nun chai became an accumulative gesture of care, countering violence and its representation and hopefully building a kind of potentiality. Interestingly, the final cups of nun chai took place during Ramadan, a month of fasting. So, people represent the nun chai with their empty hands, through its absence. I think this speaks to the adaptive ways in which the work has unfolded.

As someone not from Kashmir, I was very conscious of the responsibility of representation and its consequences. Although Kashmir is incredibly photogenic, I never felt comfortable directing a camera at it. Intuiting the limits of representation and wrestling with its violence; the space of conversation, memory and words became a means of conveying what I did not feel capable of capturing through images.

It is interesting now to see the responses to the book from the photography community. In a recent podcast with Chobi Mela, Sanjay Kak, publisher and founder of Yaarbal Books, described Cups of nun chai as being “…an anti-photobook”—and in a sense this is accurate. Although it is somewhat circular in the way, that, the form began from a distinct discomfort with the limits of images. Perhaps photographers are picking up on that too.

All images from Cups of nun chai by Alana Hunt. New Delhi: Yaarbal Books, 2020. Book design and photos by Itu Chaudhuri Design.