Instinct, Ethics and Image-Making: A Conversation with Ishan Tankha

In this continuing conversation with Ketaki Varma, photojournalist Ishan Tankha elaborates on the impact of the pandemic on his work and the ethics of photojournalistic practice, especially in contemporary India.

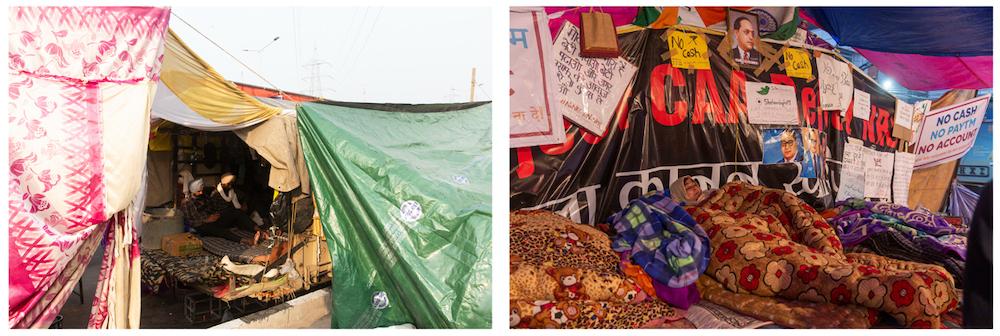

Left: Protesters at the Shaheen Bagh protest site. The protest site began with a small group of housewives from the neighborhood against the recently passed Citizenship (Amendment) Act. It morphed into one of the biggest peaceful protest movements, sparking scores of protests across the country with many thousands joining in. Later, the site was completely cleared and all visible signs such as graffiti and posters were removed or painted over in the first few days of the Covid-19 lockdown. (Delhi, January 2020.)

Right: A group of workers from a shoe factory pose for a photograph on the Delhi-Meerut highway as they make their way back to their villages after the sudden lockdown shut their work place. In the absence of any work and wages it is impossible for most to continue living in the city. The sudden lockdown resulted in hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and daily wage earners being forced to walk back many hundreds of kilometres to their homes in the absence of any public transport. (Delhi, April 2020.)

Ketaki Varma (KV): As a photojournalist, much of your work relies on documenting the contemporary moment: building visual contexts for people, places and politics. How did Covid-19 affect your process?

Ishan Tankha (IT): When the pandemic started, I had no plans of going out as it would have put the people around me at grave risk. When I went out to get groceries during the lockdown, the first thing I felt was the absence of the welfare state. The only thing I saw was the police—and they were not helping people. There was no help for anyone who was on the street. As I drove around my neighbourhood, I realised the sheer number of people—desperate and on foot—hordes of “migrant workers” struggling to get home. Honestly, had I not seen it myself, I may not have believed the scale of it and that, in a sense, made me want to document it.

Of course, the pandemic made me function differently, I was wearing mask and gloves and sanitising every time I touched something while outside. So yes, there was a change in process. Besides that, it did not really affect what or at least the way I shoot. The pictures that I have been making over the past year and a half have been about national events that have been taking place locally. Photojournalists (usually) end up going far to find stories, but this was happening all around Delhi—my own city—and its outskirts, and that was the biggest difference in process. It was in many ways helpful because I was familiar with the area and I knew how to function there.

Left: A man clutches his bag as he waits to board a bus after the government began a few buses to transport stranded migrant workers home. (Delhi, May 2020.)

Right: Students and other peaceful protesters hold hands as they chant slogans against the recently approved Citizenship (Amendment) Act that they believe is against principles of equality and discriminates against Muslims. (Delhi, January 2020.)

KV: In an interview, you were described as someone with "impeccable instincts." Can you elaborate on the idea of instinct when it comes to photojournalism? Particularly its intersection with ethics, bias and objectivity in the context of potentially volatile situations?

IT: I think instinct is very important in any sort of fast changing, on the ground situation. And maybe calling it “instinct” is limiting, maybe it is just experience. Experience bolsters one’s instincts. That does not mean it will always keep you safe but you might react better to situations.

Let me expand on the question of ethics… One advantage that photographers have is that their work does not always need to go live immediately. There is a review process between making an image and then sending it off for publication. So, for example, after working in a situation like the riots in North East Delhi, I may realise on looking through my images that at a particular moment perhaps I was too close to a grieving subject, that I should have stepped back. During the riots, there were obviously many situations where families were devastated, and there was a mad rush by the media to get visuals… These were already congested lanes and working-class houses with little space to spare. If I was there on my own, would I be standing eight inches from a grieving mother’s face? No. But when you have fifty cameras and journalists with microphones jostling and pushing on you, you might find yourself closer than you intended on being. Does that mean that that becomes my go-to picture, my lead image? Depends on your aesthetic, but it would not be the first image that I would use.

Left: A women squats on the ground, tired from waiting for her turn at a government organised testing facility after her locality was declared a "hotspot" for Covid-19. (Delhi, April 2020.)

Right: A family waits by the side of the highway on the outskirts of Delhi after they were not allowed to continue on foot to their villages by the police. (Delhi, May 2020.)

I understand for working photographers it is difficult to not make certain types of images which are expected by their employers. As an independent photographer, I am bound relatively less by such constraints. So, I could maybe step back a little and instead lead with the image that I managed a few seconds after I extricated myself from the scrum. An image that shows the media surrounding a grieving mother, a mob that I am also a part of.

Left: Farmers near the border of New Delhi and Uttar Pradesh rest in makeshift tents setup on the highway in protest against the farm bills introduced by the government. (National Capital Region, December 2020.)

Right: Women brave the extreme Delhi cold at the twenty-four hour Shaheen Bagh protest site. (Delhi, January 2020.)

While we are on the topic of ethics, I want to mention another recent incident that stood out for me. When the pandemic started, everyone was talking about social distancing; and it made me think of how in a country like India, the phrase “social distancing” is so fraught with problems. And then the media created the hype around the (Nizamuddin) Markaz and as a result all of Nizamuddin West was made a containment zone with no one allowed in or out. I was taking pictures from the Barapullah flyover—which sees the back of Nizamuddin West, right behind the Markaz building. I could see people at their windows or on their roofs because they were stuck there. These are small, working-class homes with many people to each room and there is little space to begin with. And there I was—standing on the flyover about 200 metres away, with a zoom lens—taking pictures of them. It felt inherently wrong. There was a lot of power in my hands, and I felt it. I heard one guy get upset, he said to me, in these exact words: “What gives you the right to stand there and take my picture while I am locked up here with no choice?” And I understood exactly what he was saying. I left, but this stayed with me. I know other photographers also had some issues making pictures from that same spot later on with the people being portrayed becoming understandably upset. So, I think it is important for photographers to understand situations like these. There are situations where one needs to fight for the right to make pictures and there are others where maybe its important also to listen and put the camera away and try a different way to tell the story.

Left: A man holds on to a replica of the Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir as another throws colour in celebration, after the government conducted the ground breaking ceremony to begin the consecration of the temple for Hindu god Ram at the disputed site of Ayodhya. (Delhi, August 2020.)

Right: Even as riot police marched through North East Delhi, their presence did not seem to deter the Hindu mobs as over thirty-five Muslims were killed over four days. (Delhi, February 2020.)

All images by and courtesy of Ishan Tankha.