Building Landscapes of Feeling: Abdul Halik Azeez’s day dreamer you are

Installation View of “Big Six,” day dreamer you are at Saskia Fernando Gallery. (Colombo, 2021.)

Sri Lankan photographer and filmmaker Abdul Halik Azeez’s second solo day dreamer you are is an exercise in excavation. Showcased at Colombo’s Saskia Fernando Gallery over six years after his first solo, the exhibition laid bare the intersecting and often competing structures that constitute urban landscapes, deliberately looking beyond ideas of “progress” to reveal the layers of detritus that cities are built on. “Azeez shuns the monumental that has come to symbolise the designer megapolises of the future envisioned by the false prophecies of states. Instead, he pieces together the fleeting, contrasting textures that make up the uneasy humdrum of an unnamed city as a montage of competing cruelties and aspirations,” explains Vindhya Buthpitiya in her catalogue foreword.

In the first of a two-part conversation with Ketaki Varma, Azeez describes the making of this exhibition, his relationship with the city, and his love for zines.

Ketaki Varma (KV): day dreamer you are is a disconcerting exhibition. As the curatorial note mentions, it is a piecing together of the various textures that make the urban landscape a space of dangerously overlapping dreams, destruction, development and debris. Tell us about the making of this solo—your curatorial vision, the title and the creating of these images.

Abdul Halik Azeez (AHA): A lot of my images are shaped by encounters: I have always responded to things that I come across, wherever I have had the opportunity to observe. And I have been thinking a lot about a discourse, which I suppose can be called “anti-developmental,” but is one that actually questions the problems of growth. We are conditioned to believe in this idea of development, especially in Sri Lanka, where we have seen this pro-development ideology accelerate at a great pace.

Installation View of day dreamer you are 35 and 36 at Saskia Fernando Gallery. (Colombo, 2021.)

After the war, for about thirty years, we had a stagnant urban space. Then, a few things started to happen. An obsession with making Colombo a world-class city emerged. This was a very visual obsession—because when you think about a fast-paced city, you think of New York or London and their huge monuments. I became interested in this wave and the ways in which it translated materially on the ground. For instance, in Central Colombo, many neighbourhoods that had survived for generations were uprooted and replaced by what are essentially gated high-rises, and their original inhabitants have been transported far away from the city. These actions disregard the social and cultural needs of the people. The high-rises that occupy these spaces now are shopping complexes or apartments. Such apartments are not bought or lived in by local communities; a lot of them end up being investment vehicles for the ultra-rich, which turns them into sort of ghost towns. As a result, real estate prices in the city have gone up, home-owners or renters have gotten priced out and people have suffered. Despite this, the obsession with shiny, globalised facades continues due to which lifestyles, food habits and ideas of leisure are changing.

I have documented a lot of this in the past, as a photojournalist and a researcher. However, when I started thinking more closely about Colombo in 2019–20, I realised that I can no longer consider these ideas simply as a photojournalist or researcher. Those kinds of frames and points of views are not enough to encompass the paradoxes and multitude of things that are going on. That is why I began to think about Colombo and the idea of growth from a psychogeographic perspective—in terms of emotional landscapes and maps of feeling—which then became the basis for this show.

Installation View of day dreamer you are 3, 4, 2, 1 and 5 at Saskia Fernando Gallery. (Colombo, 2021.)

There was a zine I had made—that kickstarted the process—that ended up in the show: a meandering sort of walk through the city, playing around with fact and fiction. In one of the zines, in fact, I consider the idea of how everything around us acquires a different meaning from what is imposed on it, and one can find these different meanings if one wants. Even if the city is a hegemonic enterprise that is trying to create meanings in things around us, those things start to undermine the very ideologies that are imposed upon them.

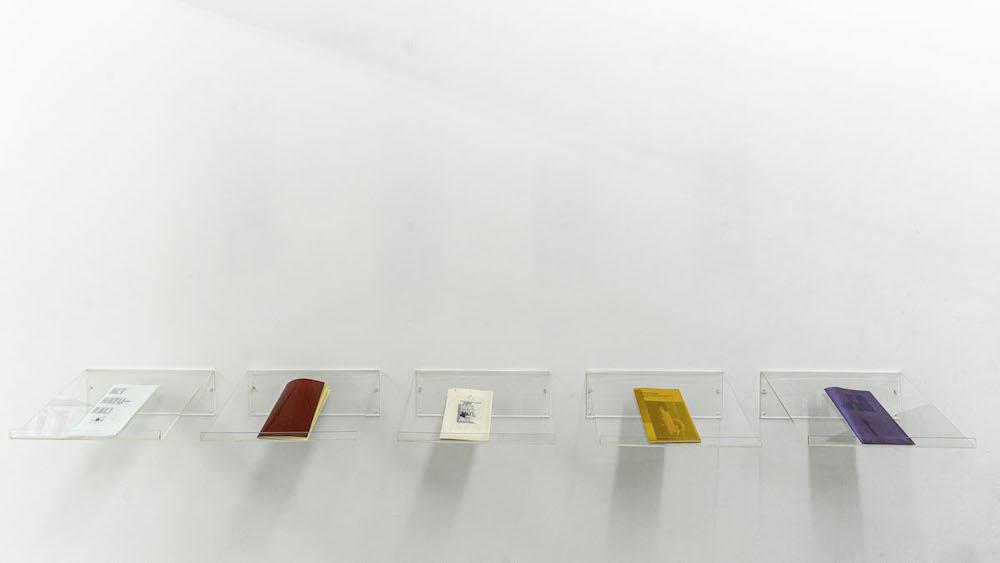

Five handmade zines placed in the space of the gallery turn the lens inwards, with a focus on the artist's life and practice. (Colombo, 2021.)

KV: Speaking of zines, you have worked extensively with them over the past few years. Could you speak about the zines in this exhibition? What does the zine format offer that other media formats do not?

AHA: For me, zines are works of art. The first time I encountered zines, I remember being very overwhelmed, because I have always wanted to make books but never had enough material to put in them. Zines offer a much more compact space to play around in, they merge your art practice with book forms. They enable all that books offer but with flexibility and space to experiment with your practice.

Considering a place like Sri Lanka—where zine culture is not that popular—I believe that they can become entry points for people to appreciate and understand art. There are a lot of people who like art but their association with the art world depends on what they can own—which are often artworks that they are priced out of—or they feel like art necessarily involves extensive infrastructures to engage with it. But zines are a great entry into collecting art, I think, because they are cheap, can be stored easily and are still limited edition works of art. They can be circulated easily and they can be rough, casual, quick and playful. I like that they can go against convention.

To read the second part of this conversation, please click here.

All works by Abdul Halik Azeez. All images courtesy of the artist and Saskia Fernando Gallery.