A True Internationalist: An Encounter with Zia Qadri

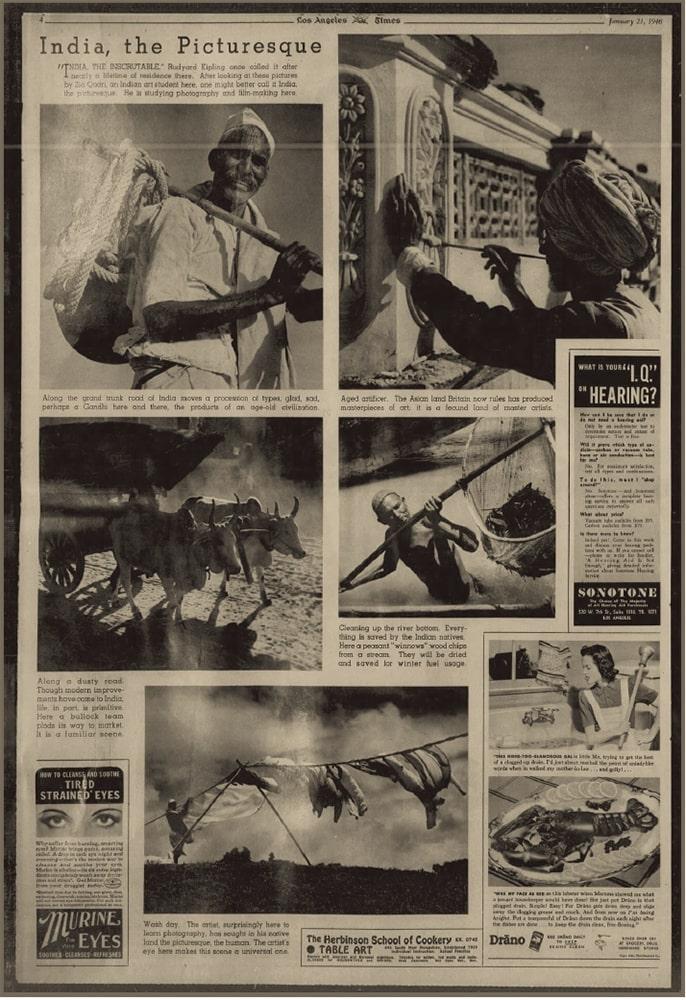

“India, the Picturesque.” (Spread from the Los Angeles Times Newspaper. Los Angeles, 21 January 1940. Image courtesy of Newspapers.com.)

The Los Angeles Times newspaper edition from 21 January 1940 featured a full spread titled “India, the Picturesque.” Showcasing documentary images of everyday India—a washerman, a pair of bullocks and a portrait of a peasant—these were scenes with a certain simplicity, to which Ziaudion Mustafahasan Qadri brought an aesthetic perspective. At that time, Qadri was an Indian student of photography and film at the ArtCenter School in Los Angeles (which is now known as ArtCenter College of Design). These images were my first introduction to the work of this modernist photographer.

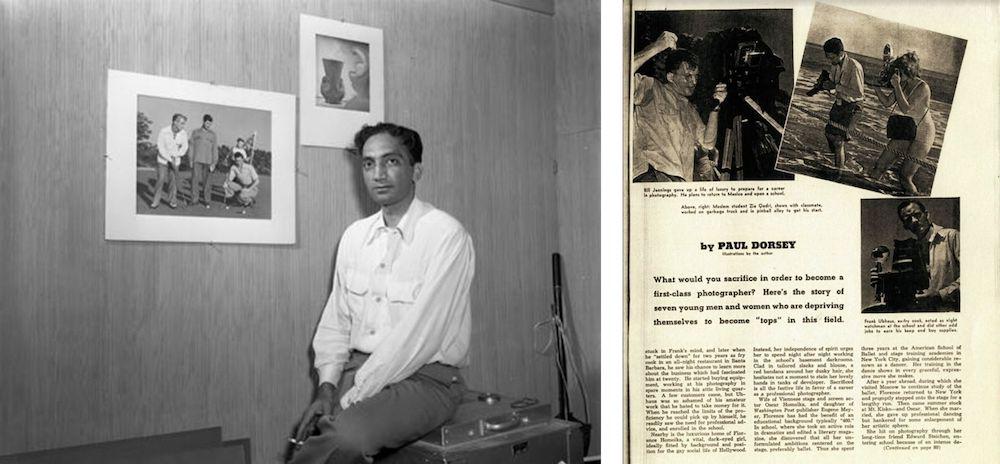

Left: Portrait of Zia Qadri sitting on a piece of film equipment in his studio in San Francisco. (San Francisco, c. 1955. Image courtesy of the ArtCenter College of Design Archives.)

Right: “Anything for Photography,” featuring Zia Qadri (Top row, right). (Photographs by Paul Dorsey. In Popular Photography. United States of America, November 1942. Image courtesy of Google Books.)

Born in Ahmedabad in 1916, Qadri was encouraged by his family at the age of fifteen to photograph the widely attended golden jubilee ceremony of the Maharaja of Baroda. Unable to manoeuvre through the fleet of European photographers at the event, Qadri climbed up to a higher position. Much to his surprise, his photograph got featured in the Times of India. Although this sparked an initial interest in photography, he went on to join the Poona Agricultural College before moving to Los Angeles to pursue a career in photography.

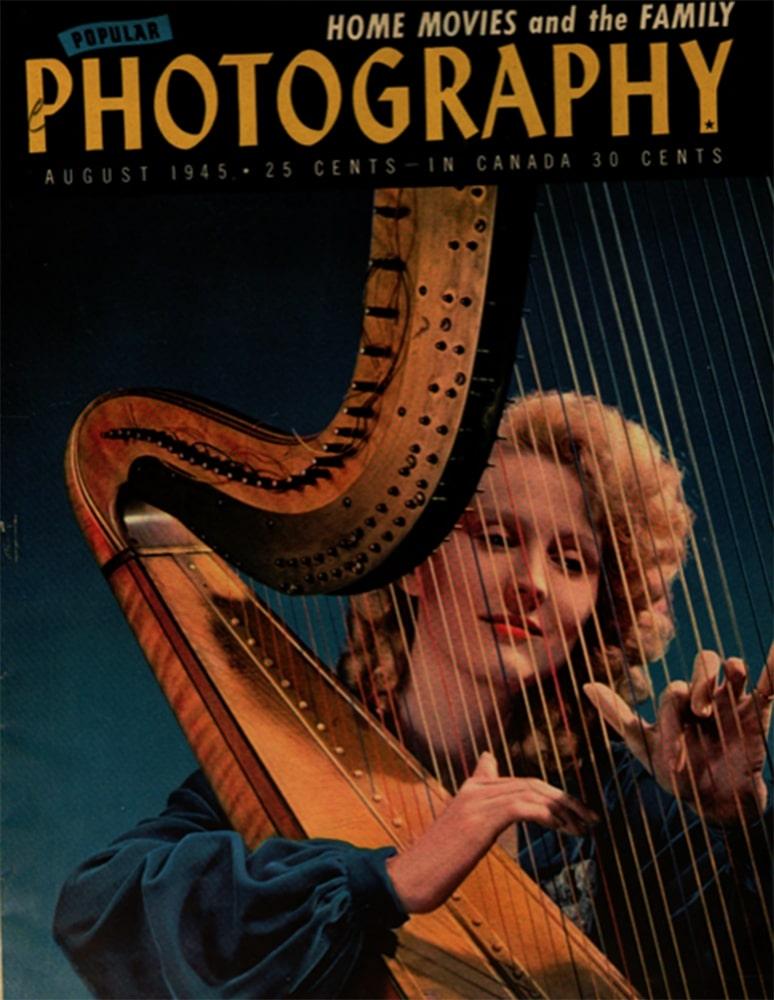

Qadri’s photograph of Margo Freeman, a harpist, was featured on the cover of Popular Photography’s August 1945 issue. (Photograph by Zia Qadri. In Popular Photography. United States of America, August 1945. Image courtesy of Google Books.)

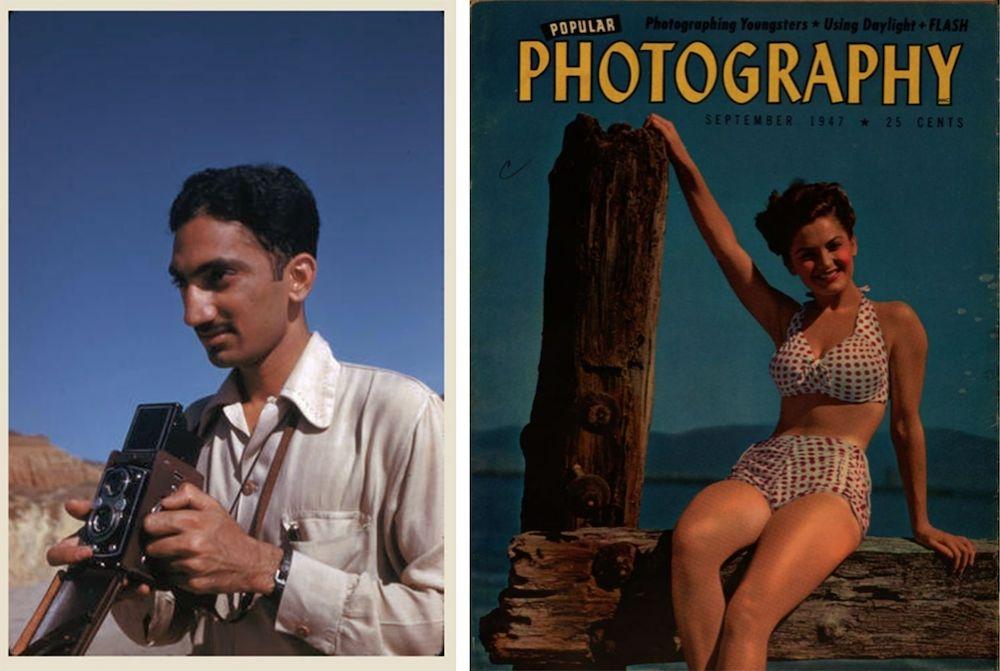

Soon after he had landed in Los Angeles, he was featured in the Los Angeles Times newspaper. Following this, his images accompanied an article by prominent American journalist Edgar Snow in the Saturday Evening Post. In particular, through several mentions in the 1940s within the American photography magazine, Popular Photography, one might gather the expansive breadth of Qadri's oeuvre. Having previously been known mostly for his photojournalistic imagery, the work featured in Popular Photography revealed Qadri’s experimentations with the medium. As a student, he explored several aspects such as composition, montages and other photographic techniques. One particular image showing a high-heeled boot in the foreground, with a rain-soaked umbrella in the background, is a striking example of his use of the modernist aesthetic—with its dramatic lighting and sharp-focus objective imagery—recognisable in the works of photographers like Paul Strand and popularised by Alfred Steiglitz and his journal Camera Work. Some of his montages also presented influences of surrealism in their composition. For instance, a feature on Qadri’s technique in the Los Angeles Times in December 1952 includes an image of marbles shot with a view camera and two spotlights. This set up created the illusion of wings, making the marbles appear like fireflies within the frame. Such images show Qadri’s enthusiasm for the medium and penchant for experimentation. The strong sense of lighting in his compositions is particularly central to his montage work. Two of Qadri’s covers for Popular Photography (1945 and 1947) are colour portraits of women, both very different in the style of composition but composed as glamourous cover images.

Left: Zia Qadri on a Field Trip at the Beach. (Photograph by Richard Ham. Malibu, 1941. Image courtesy of the ArtCenter College of Design Archives.)

Right: Qadri’s image of Norma Crieger at a South California Beach was featured as the cover of Popular Photography’s September 1947 issue. (Photograph by Zia Qadri. In Popular Photography. United States of America, September 1947. Image courtesy of Google Books.)

Despite economic hardships during the initial years leading to garbage truck and pinball alley jobs, he eventually joined the illustrator Andrew Loomis—known for the Loomis method—as his studio photographer. During this time, he also became passionate about colour photography. He started making his own colour prints, using carbro printing (Carbon + Bromide)—a labour intensive process, involving the interaction between pigmented carbon tissues and a silver bromide print. He also experimented with dye imbibition, commonly called dye transfer processes—involving separate colour negatives enlarged into gelatin matrices and immersed in cyan, magenta and yellow dyes. Subsequently he joined the ArtCenter as an instructor for colour photography. A few years later, he joined photographer Alfred T. Palmer and helped set up the commercial photo studio, “House of Photography” for assignments in colour.

Pearls in the Pond was selected as “Picture of the Month” in November 1944 by Popular Photography magazine. (Photograph by Zia Qadri. In Popular Photography. United States of America, November 1944.)

The Los Angeles Times' 1940 feature described Qadri’s work in the following manner: “(The artist’s approach) makes the scenes (he shoots) universal.” Even prior to formal training, Qadri’s work revealed a penchant for experimentation with the apparatus and the medium. It is evident that his education in Los Angeles exposed him to other artistic movements within photography, influences of which are clearly seen in his work. The 1945 issue of Popular Photography featured him alongside Ambalal Patel, a prominent camera equipment dealer in Mumbai whose contributions to film and photography in India gave him prominence in the West. Though featured together as “Indian photographers,” there was a vast difference between the two, apart from their stylistic preferences. Qadri’s practice after the 1940s was confined to the West, while Patel’s work was focused on India. Thus, it would be hard to read Qadri’s work for an understanding of photography in India at the time. However, it is reflective of an international enthusiasm for photography that made such cross-continental exchanges of ideas and individuals possible.