Technologies of Vision: A Conversation with Artist Aziz Hazara and Curator Muheb Esmat

This conversation with artist Aziz Hazara and curator Muheb Esmat came out of Sukanya Baskar's experience of having viewed No End in Sight, an exhibition that they recently put together at the Hessel Museum in New York. Hazara, a multidisciplinary artist, and Esmat, a curator and an artist as well, have both been deeply engaged with the portrayal of different aspects of growing up in a war-torn Kabul, Afghanistan.

Esmat has worked and written extensively on aspects of visual culture in Afghanistan. He is particularly interested in the hybrid influences that create the visual landscape—from signs in one's immediate surroundings like automobile signs and urban graffiti to expressions of these within the endless expanse of social media. Through these mundane and occasionally comedic instances, Esmat reflects on the pain and trauma of a constant state of war that shapes art and these visual manifestations.

Hazara works across photography, moving image, sound and language programming. He combines ideas of personal and collective memory to reflect on the nation’s long history of war. His work often employs technology born out of the war to represent its effects and in a way, its normalisation. He has exhibited extensively across the world, including at the Biennale of Sydney 2020, Kunsthal Aarhus, Denmark and the 2020 Busan Biennale among others.

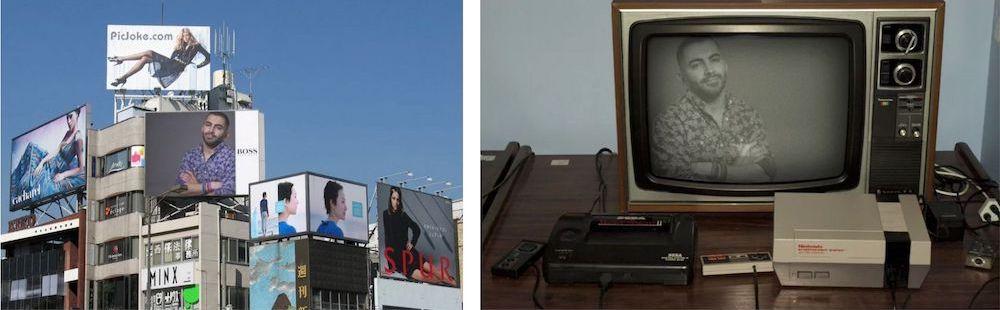

Left: Kite Balloon. (Aziz Hazara. Kabul, 2018. Digital Photograph.)

Right: Installation View of No End in Sight at the Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson. (Aziz Hazara. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. New York, 2020.)

Sukanya Baskar (SB): Through all of your work, you have remained deeply entrenched in the geopolitics and the never-ending conflict afflicting Afghanistan. There are many social and cultural links to other parts of South Asia such as India or Pakistan. Are these conscious links that you seek to bring into your work?

Aziz Hazara (AH): I am fascinated by the interconnectivity of political, social and historical events in the subcontinent. As someone who speaks the multiple local languages of our region, it is curious to see how a poem travelled from Delhi to be recited in Lahore and then arrived in Kabul and vice versa. It is incredible to see how different schools of thought coexist across the region and generate a diversity of approaches in responding to the everyday. Historical and contemporary literature as well as traditional forms of knowledge passed down through generations in the form of rituals in the subcontinent inspire me and my artistic work immensely. All of these contribute to the storytelling and narrative building in my works.

SB: Within the context of war, image-making practices may be seen as a weapon of the invader. Could you shed some light on how you counteract that through your own use of technology—such as surveillance technology—within your image-making practice?

AH: I make images with what is available around me. Growing up in Kabul, I witnessed a city flooded by second-hand military equipment as objects that entered into everyday life and became part of collective memory. In Kabul's secondary markets, one can find military equipment left from the Soviets next to night vision goggles used by the Americans on the same shelf. In a sense, my work with image-making technologies is driven by their overwhelming presence in Afghanistan's public sphere.

We live in a time where surveillance is becoming more and more technologically advanced. The surveillance state's long-term consequences for Afghan society are massive as it lacks the basic social and judicial structures that could guarantee citizens' rights. Hence, my interest lies in the performative dimension of technological surveillance and the social and ethical considerations thereby cast aside.

(SB): Growing up in Kabul yourself, and witnessing the years in which the United States of America invaded Afghanistan; what made you decide to bring Hazara’s work to America for a show?

Muheb Esmat (ME): Part of my curatorial research centres around the role of images and visual media in contemporary life. I have been interested in exploring the role of images in Afghanistan. In the course of this research, I was quite shocked to see how photojournalism has become the sole representation of image-making from the country. Being aware of how photojournalism tends to become a silent weapon in an ideological battleground in conflict zones, I thought it might be more interesting to show the kind of works local artists are making using cameras.

I had admired Hazara’s works for a while. So, I reached out to him and through our conversations, we decided on the framework for the exhibition No End in Sight. There is an urgent need for critical reflection on the United States of America’s war in Afghanistan. Considering the fact that our exhibition was being held at the Hessel Museum of Art in New York, it felt important that the three bodies of work—across photography and video installation—presented as part of the exhibition explored the role that technologies of vision play in the United States of America’s war in Afghanistan.

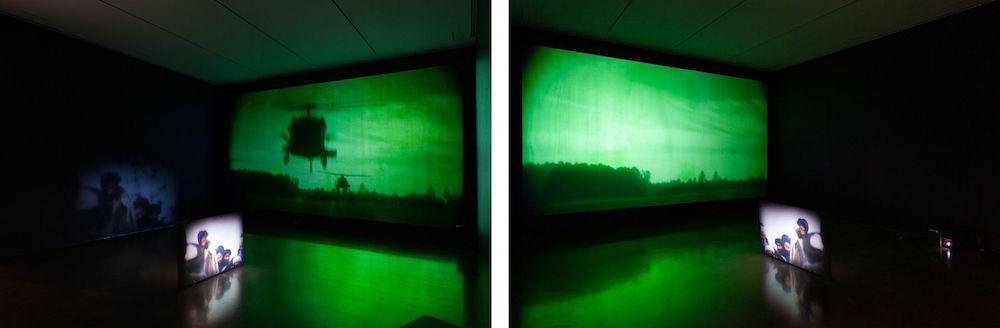

Installation View of No End in Sight at the Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson. (Aziz Hazara. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. New York, 2020.)

SB: Could you speak about how Hazara’s use of technology and his techniques of image-making (for example, the images in “Camouflage”) feature a larger political history of Afghanistan?

ME: I think what differentiates Hazara is not his use of technology; it is that his work takes a critical look at these technologies and their place in Afghan society. For instance, the “Camouflage” work you mentioned is a series of monochromatic green photographs taken by the artist using military night vision equipment. Used for night raids, this optoelectronic device lets soldiers construct images of their surroundings in low levels of light, enabling them to be disguised by the dark. These operations are built on the lack of visibility, leaving the subject with little to no idea of the parties involved. Night raids or “Capture or Kill” operations are a military tactic first used by the United States Army in Afghanistan. They have since been passed down to and adopted by the local CIA-trained paramilitary forces and Afghan Special Forces.

In one of the photographs—imagining the moment before a raid—Hazara photographs a man wrapped in a white scarf standing in front of the giant wooden gate, staring directly at the camera in suspicion and fear. Hazara situates the viewer as a witness to a deplorable act—both through the eyes of the soldier and the bodies of the subjects after. Standing outside of the home and at a distance from his subjects, the artist captures traumatised and desolate bodies with a vast barren horizon behind them. The viewer is invited to see the image that no soldier stays behind to witness: the pain, loss, uncertainty and the inability to seek any justice, as local and foreign forces have continuously swept their war crimes under the rug.

The political history of Afghanistan is full of complexities, to say the least. What we do know is that the longer this war continues, the deeper its trauma will be. Through No End in Sight, I wanted to show how Hazara steps beyond the immediate representations—sought through emphatic portrayals of physical loss—to probe the invisible mechanisms of war and their long-term impacts on society. Alternatively, I also wanted to show that artists like Hazara—who take a critical look at and shine a light on the consequences of this continuing turmoil—play a major role in any hope for a different future.

Images courtesy of the artist and the curator.