Traces of Occupation: Kashmir, A State of Erasure

“Trauma is viewed as pre-verbal and timeless—still and urgent,” reads the description of video works Nishan I (2007–12) and Nishan II (2019) by Desire Machine Collective, the collaborative identity of artist duo Mriganka Madhukaillya and Sonal Jain. Nishan I and Nishan II document a house previously occupied by a family of Kashmiri Pandits in downtown Rainawari, in Srinagar, Kashmir—a locality that used to be a hotbed of militancy—later reassigned to become an Indian army barrack. The house was eventually abandoned in 2007 once the insurgency ebbed.

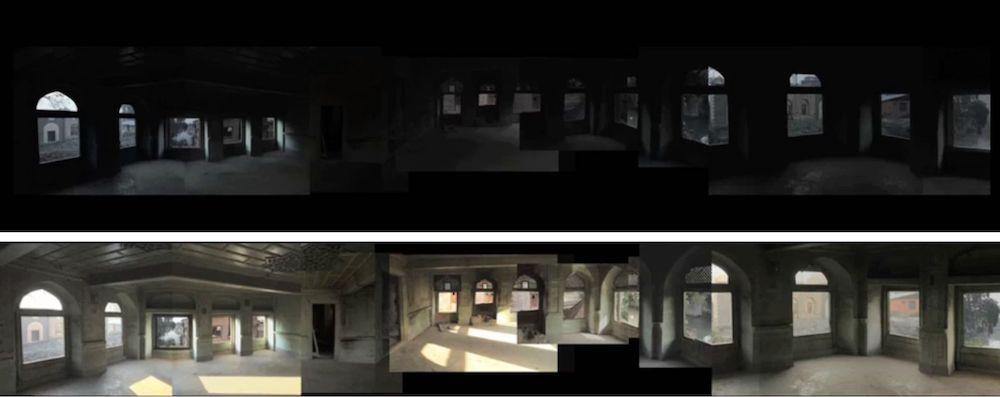

Stills from Nishan I. (Srinagar, 2007-2012. Four-Channel Audio-Video Installation.)

Nishan I is a four-channel audio-video installation originally shown at the Guggenheim Museum, New York. It consists of hundreds of videos that have been stitched together to form a video collage. The original installation was forty-feet across, running along the breadth of the gallery; creating an immersive visual and sonic experience. The soundscape consists of incoherent noises captured from the conversations that the duo recorded on site. These have been reversed and muffled to create what sounds like laboured, almost mechanised breathing. Creating the experience of a rapid, irregular heartbeat that runs throughout, it (re)produces a distressing effect that is meant to overwhelm the viewer. It is almost as if the derelict, battered house is a living, breathing organism—that Jain describes as being a repository of memories.

Installation View of Nishan I at the Guggenheim Museum. (New York, 2012.)

When the artist duo visited Rainawari, the neighbours gave them testimonials, recounting their memories. One in particular was about a Chinar tree outside that was perpetually in full bloom, up until the militancy, when it is said to have stopped. The Urdu word nishan means a mark; the artists employ it as a marking in time, as traces of evidence in the context of Kashmir’s complex present. Time plays a key role in the work, as Jain mentions in a telephonic conversation. For them, entering that particular house was like going into a different time zone. They also experienced a different sense of time, as its linearity seemed to break—described to be an effect of trauma. Through the hundreds of videos they took, they documented different times—such that every window in the installation is a different world. For instance, one shows a temple, while another captures the sounds of birds and the azan or call to prayer (though these are made to be incoherent).

Referencing miniature paintings, the video work makes use of multiple points of view. By breaking the single point perspective, the artists seek to subvert the colonisation of vision. Jain spoke to me about the European Renaissance governing our gaze and informing postcolonial sight. Their video work thus attempts to break the singular image of the film through a “…collusion of different perspectives.”

Jain describes the project as depicting “…sensory disorders that result from a disruption of organic flows." These occur due to sustained conflict and the breaking of linear time through the setting in of trauma. The windows in the video expose the internalised nature of surveillance and violence. In a state of constant erasure and disappearance, all that is discernible is rubble and quiet buildings. Kashmir itself is under these conditions, a situation exacerbated by the Indian nation-state’s abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. While Kashmir’s political, social and administrative autonomy has been consistently eroded over the last decades, the autocratic abrogation by the ruling Hindutva Bharatiya Janata Party paved the way for the revocation of Article 35A. This allowed the Indian state to begin its settler-colonial project with the newly instilled legal right to buy land in the state. For decades, the valley has been rife with series of enforced disappearances of young men suspected to be insurgents; and forced to witness the erasure of sovereignty, security, human rights and accountability.

Stills from Nishan II. (Srinagar, 2019. Two-Channel Audio-Video Installation.)

Nishan II (2019) is a two-channel audio-video installation commissioned by the Singapore Biennale. Here, the same house (from Nishan I) is visualised, as the camera pans in a 360-degree viewing of the space. The two channels rotate around the derelict interior in opposite motions—eventually converging, overlapping and moving across. Jain reminds me that as a military barrack, the house would have been used for interrogation and weaponised torture. This is alluded to through a further intensification of soundscape—high-pitched and rattling, one is reminded of the sound cannons or Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRADs) that have been mobilised to disperse protesters in Kashmir. These elicit a higher frequency than human sonic range, and can not only cause damage to auditory sensation but also to one’s internal organs. We can see this as a literalisation of the “disruption of organic flows.”

Stills from Nishan II. (Srinagar, 2019. Two-Channel Audio-Video Installation.)

What is striking in this work is that a military presence always frames this inundating reality—that never shifts, only worsens. Nishan II seems to indicate towards an accelerated degradation of the senses. As the stillness of the house is juxtaposed with the circular motion of the camera, one wonders: how do we define the everyday experiences of residing in a state of constant conflict? As time and organic flows are said to be disrupted, what can we make of the ailing body, or personal and collective grief?

Ackbar Abbas in his book Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance writes, “(Disappearance) is also the (negative) experience of an invisible order of things, always teetering just on the brink of consciousness.” The state of Kashmir is absent in the works, mirroring a built environment of invisibility. Kashmir is not visualised, nor is it referred to outright. The situatedness of trauma resides in the disposition of the house, as in the body. With the enactment of long-term dispossession, the effect produced is of a constant state of internal and external conflict on the body (which is not separate from the mind). Memory becomes an ailing apparatus. No physical traces remain of a lived space. Here, “occupation” connotes both the inhabiting of a place as well as a state of systemic political and religious colonisation. As an altogether forgotten state—after the revocation of its special status, internet shutdowns and a state of total lockdown—Kashmir has been dismissed from the public consciousness of mainland India. It is always in a state of post-violence/ violation. In these installations, a missing Kashmir produces a haunting in the present.

All works by Desire Machine Collective. Images courtesy of the artists.