Freedom on Screen: Bangladesh's Short Film as Alternative Cinema

Filmmakers and scholars (including John Hood) have argued for the recognition of Zahir Raihan’s short documentary Stop Genocide as the first short film of Bangladesh. Made during the 1971 struggle, its use of the documentary form to convey the immediacy of the tragedy determined some of the crucial elements of the short film as an alternative film form in Bangladesh and its inevitable politics of resistance against the conservative-restorative tendencies of the state. (Still from Stop Genocide. Dir. Zahir Raihan. 1971.)

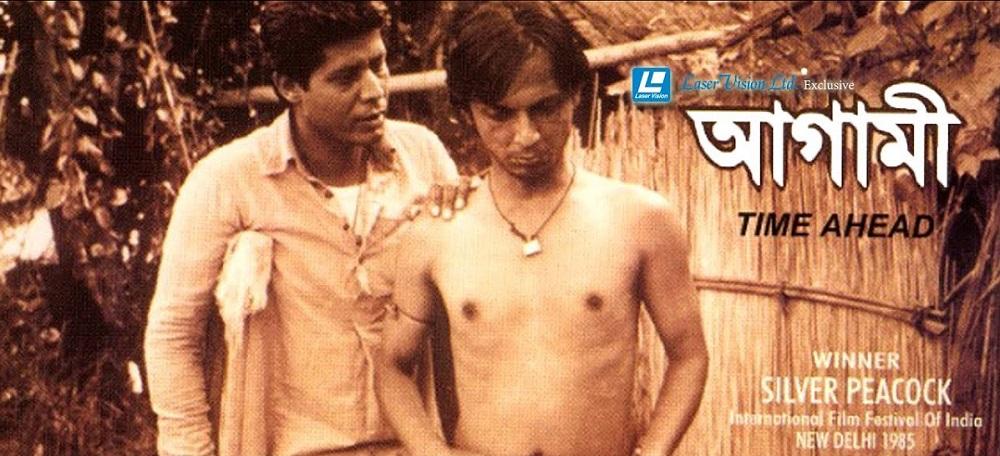

The short film plays an outsized role in Bangladesh’s cinematic history. The term “short film” might only signify a film of shorter duration than the average theatrically distributed commercial-industrial film in the mind of a viewer; but in its historical development, social linkages and modes of production lie the hidden narratives of a struggle for self-expression by Bangladeshi filmmakers and audiences. The evolution of the form in Bangladesh reveals the traces of this struggle between filmmakers trying to wrest an autonomous form from the predations of state control. A key aspect in this was the memorialisation of the Liberation Struggle of 1971 as a cultural moment that defined the identity of a country and set the agenda for their political progress. It is not surprising, therefore, to note that the short film came of age in the mid-1980s (when a conservative military dictatorship was in power and committed to reversing the secular, nationalistic gains of the Liberation Struggle). This moment emerged around the nucleus of a controversial film, Agami (Forthcoming, 1984), and as a culmination of several decades of film society movements going back at least to the 1960s, before the formation of Bangladesh. Fahmida Akhter writes,

“These films are committed to adopting strategies different from the practices associated with the mainstream film industry both in stylistic and in economic terms. In order to earn greater freedom on screen, the directors of such films, in most cases, produce and distribute their films by themselves, avoiding the tyrannies of the producers and distributers of commercial films.”

Morshedul Islam was a product of the film society movements in Bangladesh. As Fahmida Akhter writes, “Before the film’s release in 1984, the authorities of the Bangladesh Film Censor Board initially refused to issue a censorship certificate for Agami. The film’s use of the words ‘Joi Bangla’ (victory to Bengal), ‘Razakar,’ ‘Pakistan,’ and various pieces of rural slang in the film’s dialogue was cited as the main reasons for the Board’s refusal to issue the film with a certificate.” Like alternative film traditions elsewhere in South Asia—censorship struggles are an important indicator of their public worth. (Poster for Agami. Dir. Morshedul Islam. 1984.)

As writers and filmmakers like Tanvir Mokammel have suggested, the temporal distinction is not as significant as the conception of an “alternative” mode of making films for a politically conscious audience, thereby marking Bangladesh’s own contribution to the globally southern discourses of Third Cinema and third world cinema. Mokammel, in fact, suggests the use of the term “muktodoirghor cholochhitro” (free-length film), suggesting the implications of a freedom from temporal linearity or even the poetic liberty of free versifying. These films were identifiable for their form, usually shot on 16mm film, with minimal budgets, so that production values remained low. In an essay in his book Cinema Bhabna (2018), Mokammel rues this: “Bad prints and weak soundtracks were the perpetual lot for short films.” He also hopes, however, that the short film can move beyond its most immediate and identifiable instinct for critical reportage and develop more complex ways of representing the political and social landscapes of a changing nation like Bangladesh. As titles like Agami make it clear however, embodying a hope for the future is another firm characteristic of the short film as alternative cinema in Bangladesh.

One of the most important filmmaking pairs of Bangladesh, Tareque and Catherine Masud made several full-length features as well as shorts like Noroshundor (The Barbershop, 2009). While Noroshundor was made decades after the Liberation Struggle, it still sought to convey the atmosphere of paranoia and suspicion that gripped ordinary residents during the war. (Video Still from Noroshundor. Dir. Tareque and Catherine Masud. 2009.)

To read more about Bangladesh’s cinema, please click here and here.