The Lady and the Lion: Reading the Political Posters of Pakistan

.jpg)

In cities like Karachi, political posters have to struggle for visibility along with posters addressing local and national commercial initiatives, religious messages, film and fashion publicity and other kinds of subjects. (Image courtesy of Dawn, Pakistan.)

Towards the beginning of Mohammed Hanif’s dark, satirical novel on the conspiracy stories surrounding General Zia-ul-Haq’s spectacular, though unseen, death on an airplane, the narrator of A Case of Exploding Mangoes tells us how ubiquitous Zia’s face was in his country, Pakistan:

“For a brief moment you can see General Zia’s face in the clip, the last recorded memory of a much-photographed man. The middle parting in his hair glints under the sun, his unnaturally white teeth flash, his moustache does its customary little dance for the camera, but as the camera pulls out you can tell that he is not smiling. If you watch closely, you can probably tell that he is in some discomfort. He is walking the walk of a constipated man.”

During the years of his military rule, however, ordinary Pakistani citizens had little opportunity to pull out of the overwhelming authority dictated by this much-photographed face. Zia had disallowed political opposition in the country, which kept all electoral parties out. With his death, however, a period of parliamentary democracy was restored in Pakistan, lasting until 1999 when Pervez Musharaff captured power and returned the country to martial rule once again.

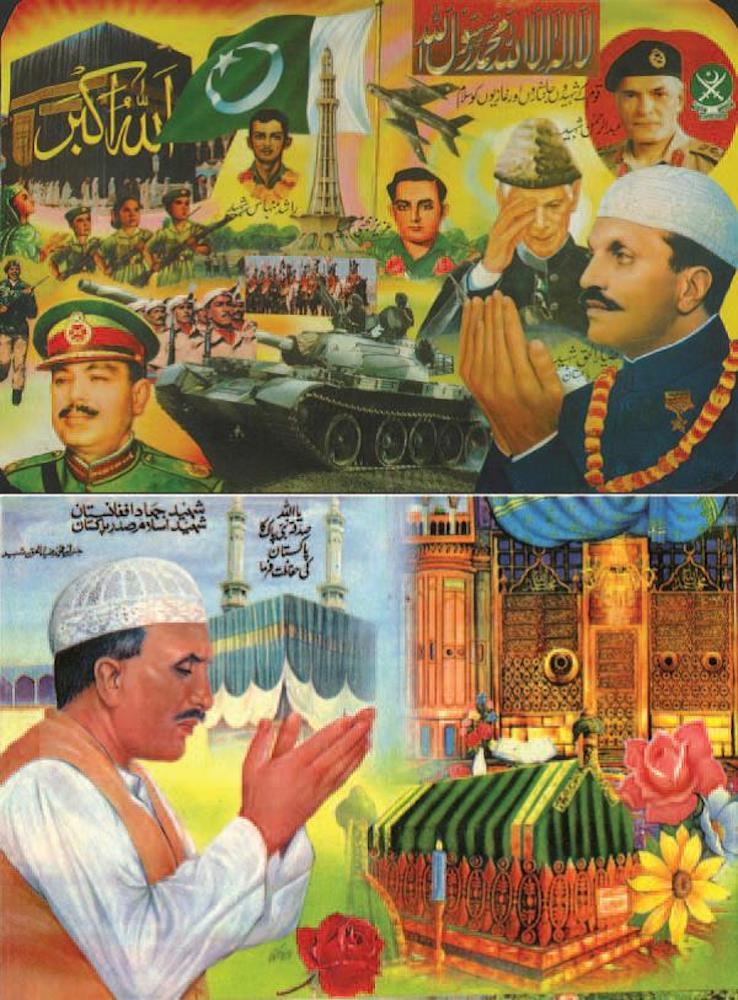

Posters like these were stuffed with motifs. Struggling to establish continuity with the disparate elements in the image, the national culture sought to unify all contradictions under a rational, public policy. Zia’s piety, M.A. Jinnah, Ayub Khan, Akhtar Abdur Rahman, and the “Heroes of two India-Pakistan wars,” Aziz Bhatti and Rashid Minhas, jostle for space with various symbols of national authority like the martial forces or monuments like the Minar-e-Pakistan (Lahore).

Even though it ultimately failed to establish itself securely in the political culture of the country, the decade-long experiment with democratic parties presented a period of rich, visual experimentation with the language of politics in the public sphere. This was primarily evident in the political posters of the Pakistan People’s Party and the Pakistan Muslim League, led by the rival charismatic leaders Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif respectively. These posters were meant to reflect the changing priorities of the Pakistani state and its attempt to influence the distinct spheres of legitimacy that existed in the country. In doing so, the public sphere had to be approached through the prism of popular, sub-national, even “vernacular” idioms that circulated freely in regions or cities of Pakistan. Thus each bore distinctive identities, shaped by their own interface with national and global cultures of a late-Cold War era of accelerating consumerism in images and lifestyle. This is not to suggest that the “popular” was somehow radically opposed to the "public" (defined as the rationalised, cultural expression of the Pakistani state-identity). Rather, both these categories were pressed into a performance of awkward compromise with each other—which gave rise to startling images, juxtapositions, allegories and conceptual associations that drove the art of the political poster in Pakistan. As Ifitkhar Dadi puts it, “The democracy decade (1988-99) lifted the stifling and boring atmosphere of the Zia years and allowed activities of diverse non-state actors to gather significant momentum in the popular realm.”

Posters circulated by Nawaz Sharif’s party—primarily the Pakistan Muslim League, later the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad—highlighted his image as a liberal moderniser with pictures of tractors and cars proliferating across the country. Others displayed scenes of him hugging distinctly non-Punjabi-looking people—to signal his willingness to unify the dominant Punjabi culture (to which he belonged) with other minor, popular communities. The motif of the lion recurs in most of his posters, creating a series of associations across masculine and martial cultures stretching back to Tipu Sultan, the ruler of erstwhile Mysore who was frequently depicted by the English as a tiger threatening the colonial enterprise in the subcontinent.

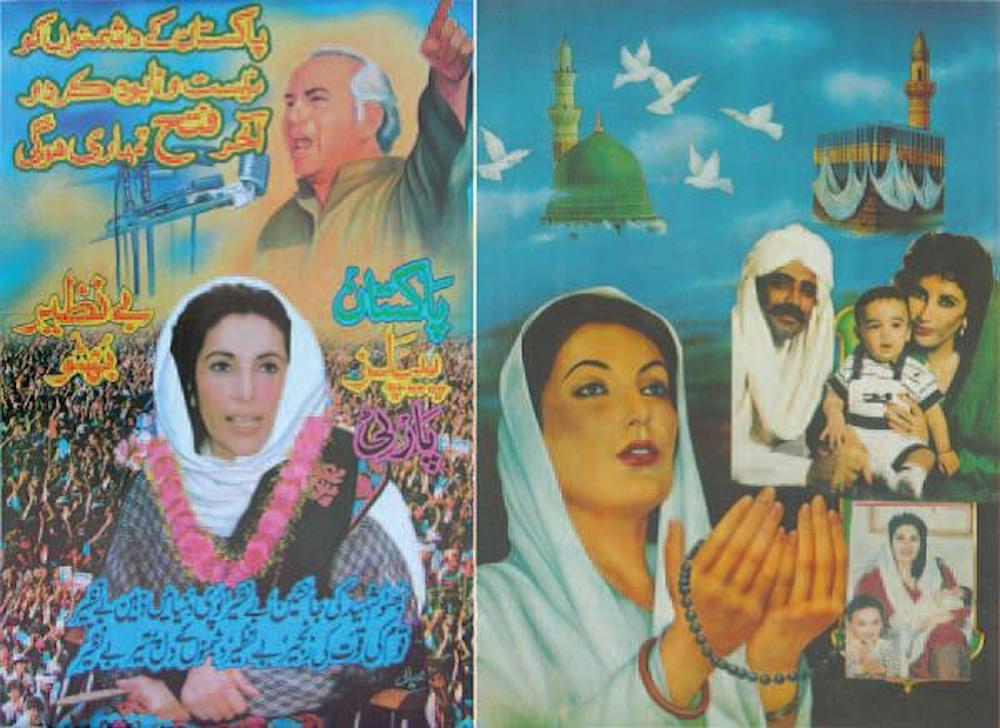

As noted above, this democratic interregnum was filled by the personalities of party leaders like Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto who had to perform a difficult balancing act. They had to cautiously celebrate Zia’s legacy of authoritarian, religious and puritanical rule, while appealing to broader currents of popular authority that allowed for a progressive, albeit fantastically corruptible, regime. This was because neither of these two leaders had any personal stake in piety—much like the liberal founder of the nation, M.A. Jinnah. This particular national anxiety was reflected in the posters too, as Jinnah himself was frequently depicted as someone approaching states of piety or at least seemingly surrounding himself with such symbols, even as the facts of his life tended to record a different reality. Similarly, these posters attest to the difficult task of coordinating a politics of populism, stage-managed by powerful (though perpetually vulnerable to the military establishment) but semi-detached elites like Sharif or Bhutto. The trace of such anxieties, it may be argued, fragmented any chance of constructing a coherent image of national politics in these posters and overwhelmed the promise of freedom that was anticipated by the sudden fall of General Zia-ul-Haq.

Benazir Bhutto’s posters frequently betrayed anxieties around her legitimacy. Her Sindhi background was marked by the odd ajrak print occasionally, but not staged (like Sharif’s gesture of hugging a Sindhi peasant). She is surrounded by traditional symbols of piety—the Kaaba and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. Instead of martial figures, she is depicted with members of her family to emphasise her acceptability to the mainstream, normative culture. The posters invite the viewer to look past her “Stilted and Anglicized” Urdu and her distinctive, but strange mode of dressing that incorporated signs of the globalised working woman as well as the traditional garb of the domestic, shalwar-kameez-wearing lady. Her greatest source of legitimacy remained, as shown in the poster to the left, her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who founded the Pakistan Peoples Party and was controversially executed by Zia-ul-Haq in 1979.

All images from “Political Posters in Karachi, 1988-1999” by Iftikar Dadi. South Asian Popular Culture, Volume 5, Issue 1. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2007. Images courtesy of Iftikar Dadi.