Camera as Imperial Technology: Looking at the Waterhouse Albums

The early history of photography in nineteenth-century British India is known for the large-scale mobilisation of the photographic camera as a technology for sustaining imperial rule. The revolt of 1857 was considered an unprecedented attack on the British imperial project. Once the rebellion was crushed, the British crown took away control over the Indian colony from the East India Company through the Government of India Act of 1858. Queen Victoria’s proclamation (November 1858) declared that thereafter India would be governed by and in the name of the British Monarch through a Secretary of State. Consequently, a phase of redefining discursive practices and strategies of imperial governance was initiated. While colonial curiosity had informed the British imperial project since the early modern period, the urgency “to know” the colonial subject was significantly renewed. In this push towards decoding the colony and its population(s), photography was appropriated as a colonial and political tool.

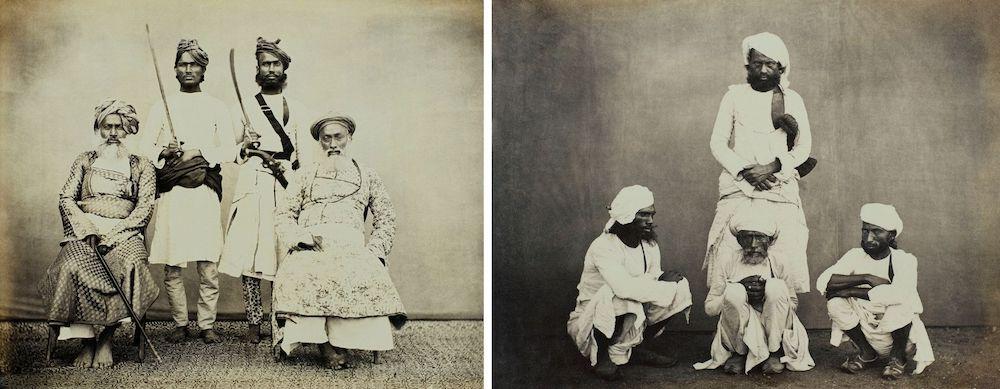

Left: Mussalmans of Mundesore, India.

Right: The Moghee, India.

In June 1861, the Office of the Governor General Lord Canning released a circular instructing colonial officers to use photography to produce visual taxonomies of the different “types” of people that lived across this vast subcontinent. The circular contained specific lists of major ethnic and tribal groups in each region and also requested the officers-turned-photographers for detailed notes on the visual characteristics of the photographed subjects and their costumes. While the official instructions did not specify the eventual purpose of this photographic expedition, the circular specifically mentioned that the images be “…large enough to exhibit.” The colonial exhibitory order found an ideal machine in the camera—owing to its capacity to combine positivist/ scientific notions of evidence with mimetic practices.

Bheels of the Vindhyas at Sardarpur, India.

As one of the recipients of Lord Canning’s circular, Second Lieutenant James Waterhouse (1842–1922) of the Royal Bengal Artillery left his regimental duties for a journey across Central India in January 1862. During his yearlong travels, Waterhouse made it to fourteen cities and towns, covering a major portion of the region Southwest to the Malwa plateau.

Rear Faces of Architraves, Northern Gateway, Sanchi, India.

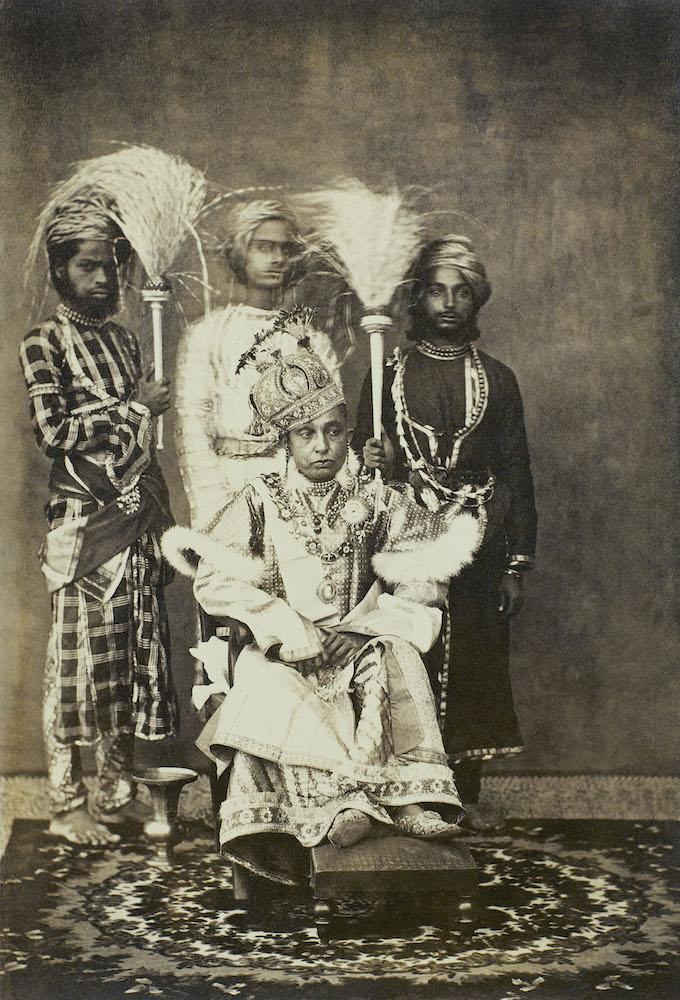

Waterhouse traversed through historical locations like Sanchi to photograph its ancient Stupas. He also paid a visit to local chiefs and rulers in the region in search of specific “native” peoples, following the official recommendations he had received before leaving. Some of the most iconic images from this collection are of the royal family of Bhopal, ruled by successive generations of formidable Begums.

Her Highness the Nawab Sikander Begum, K.S.I. of Bhopal, India.

One of the most ambitious projects to come out of this mobilisation was John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye’s The People of India (1868–75). A number of photographs from the Waterhouse collection—including the official portrait of the Nawab Sikander Begum of Bhopal—were published in several volumes of this project. Originally envisioned as a small collection, the final publication was an expansive eight volume visual catalogue of the “native” population of India categorised on the basis of various castes, culture groups and occupations—posing individually and in groups.

The Borahs. Indore, India.

This project served as one of the “Most important nineteenth-century attempts to harness photography to the service of ethnographic documentation” under the Viceroyship of Lord Canning. The importance of this publication lay in illuminating the relationship between science and photography and the development of the discipline of anthropology. The photographic archive generated in this process had many afterlives, re-employed in several British imperial projects to legitimise colonialism. However, it has also been used more recently to build a critique of the colonial gaze.

To read more about early photography in colonial India, please click here and here.

All photographs by James Waterhouse. India, 1862. These images are part of the Waterhouse Albums Volume I and II courtesy of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi, India.