Time, Malady and Detritus: Acts of Care in Naeem Mohaiemen’s Jole Dobe Na

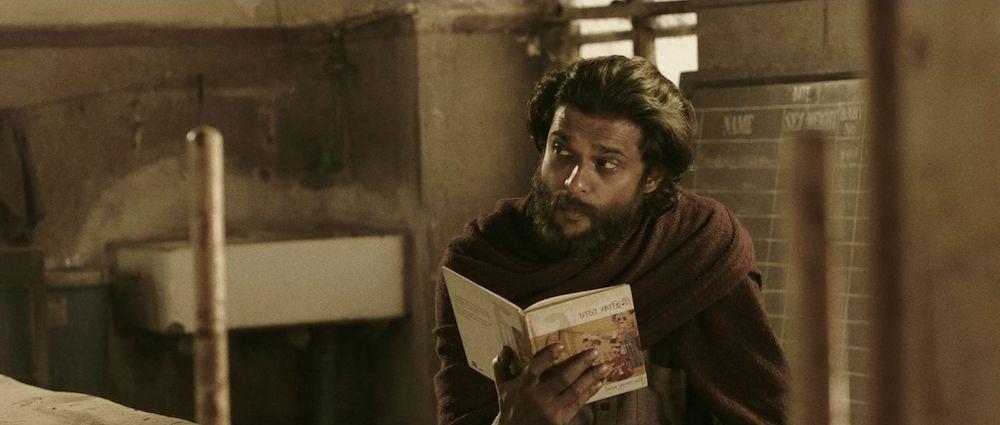

The act of caring entails attention to another body with the intention of either nursing them back to life or ensuring a peaceful death. The hospital often becomes the institutional locus of such acts of care, its estranged intimacy with patients imbuing the space with a sense of both comfort and dread. It holds the promise of western medicine and its successful navigation of the human body—one that allays pain as much as it alters its host. In Naeem Mohaiemen’s Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown)—screened at Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata, from 7 to 14 April 2021―the protagonists Jyoti and Sufiya (played by Sagnik Mukherjee and Kheya Chattopadhyay respectively) traverse the expansive landscape of an abandoned hospital (the Lohia Matri Seva Sadan) in Kolkata. Replete with clinical detritus and the conspicuous absence of a crowd and its attendant rush, time dilates on screen as the camera engages closely with the architectonics of the space, imbibing the resounding absence in its cinematic language.

The lull of this perpetual motion remains a constant motif through the film, as the narrative delves into a seemingly estranged marriage. Jyoti’s family has a history of migration from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) into India during the Partition of 1947; the loss of his homeland, Dhaka, subtly reflects in the imminent loss of his ill wife, Sufiya. The latter is often caustic—at one point, she reprimands an official, pointing out that he seems to have trouble spelling Arabic and Persian names and wonders if she should thank him for having westernised her name to “Sophia.” This is one of multiple moments that are used to detangle the political intricacies of the narrative. Other themes include the historical racialisation of medicine and consequent inequities of access, which punctuate the film through archival clips of white medical practice. At one point, Jyoti remarks that it is perhaps a sin to fall ill in a poor country. This statement resonates in the mind of the viewer in light of the current pandemic, the instrumentalisation of the vaccine to foment political unrest and the collapse of economies set forth by an invasive threat to the body.

In his multimedia work Mohaiemen uses archival material and the ambiguous spaces between definitive historical events to explore the intersecting regional histories of South Asia, transnational left politics and the possibilities of a political utopia. In his only other fictional work to date, Tripoli Cancelled (2017), Mohaiemen uses an abandoned airport in Athens, Greece as a staging ground for the navigation of confinement, loneliness and national borders, punctuated by literary annotations and epistolary addresses. In this new visual syntax, the meta-archive is reimagined through a sentient architecture.

Made in response to a prompt by the Raqs Media Collective on the afterlife of caregivers for the Yokohama Triennale 2020 (and co-funded by the contemporary art museum Bildmuseet, Sweden), Jole Dobe Na makes use of stillness and minimal registers of physical movement. With only two bodies occupying a derelict space of care, the artist manages to evoke a sense of ennui and disquiet. This is emphasised through frames and wide panning shots that place negative space in the foreground—almost as a third protagonist—while the two figures mostly occupy the margins or hover as silhouettes. The sense of disquiet is further heightened by Sukanta Majumdar’s sound design and music by Qasim Naqvi. In the suspension of time and ubiquity of material refuse, the space could also be a heterotopic cage. Can the hospital be home? Is home essentially located within the duration of the act of caring? How do the intersections of life, illness and intimacy interact with the fact of exile, which, by its very definition, constitutes an act of vulnerability in mobility? Is death as final as its announcement?

The film was conceptualised and shot prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the narrative offering an uncanny foreboding of the contemporary moment. Edited during the lockdown phase, Mohaiemen distils distances, climates, borders and prose into a concentrated space of intimacy shared by the characters. The film's narrative is ultimately about the refusal of medical care in resistance to grand narratives of science—viewed by an audience that currently lives in the hope of a scientific breakthrough to resolve a viral malady. The title of the film draws from a Bengali folk song by Abdul Alim, “Premer Mora Jole Dobe Na”, which implies that those who are immersed in love do not drown. The film, though, is less about the love that Jyoti and Sufiya share, and more about a revived regularity of habit, touch, banter and gestural navigations in the face of an impending loss. It is marked by a persistence of acts of care: even as Sufiya lies dead on the operating table, Jyoti gently runs a comb through her hair. The image lingers long enough on the screen for the viewer to question the veracity of Sufiya’s demise, as one imagines her to be still breathing. Even in this incertitude, the bodies remain buoyant; they have not drowned after all.

Bangladeshi folk song by Abdul Alim.

All images from Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) by Naeem Mohaiemen. 2020. Images courtesy of Naeem Mohaiemen and Experimenter, Kolkata.