Inheriting an Otherhood: Trauma, Domesticity and Labour in Cheryl Mukherji’s Practice

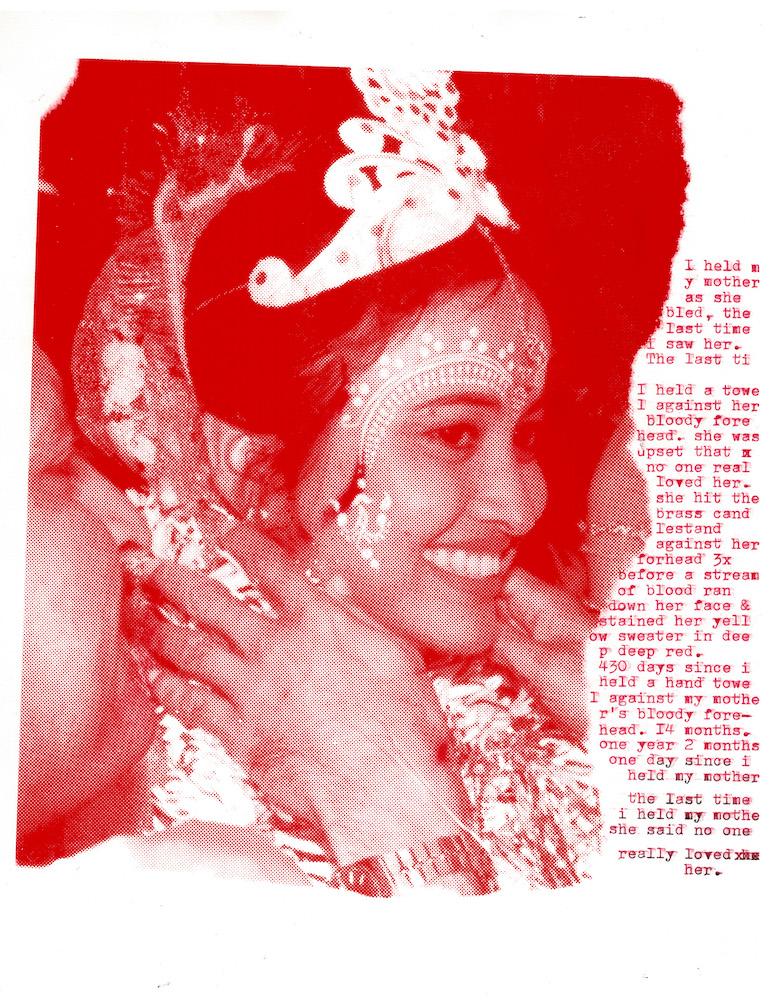

The Last Time (9). (New York, 2020. Typewritten Text on Screen Print. 8.5 × 11 inches.)

The American poet Marge Piercy writes, “My mother is my mirror and I am hers.” Summing up in one line the transference that may imbue a mother-daughter relationship, Piercy gestures to a commonality that resides in the filial as a trope: likeness. While likeness is often articulated as similitude, it also delineates an othering. There is a separateness and a diverging that helps fabricate a state of consistency between two objects or two people, creating a traceable thread of belonging. Likeness convinces us of the existence of something or someone that continues to persist in (the image of) the other.

The photograph of a person is one example of a likeness, often made to commemorate or memorialise a loved one. In such a material form, the photograph becomes an object infused with value, meaning and, importantly, the corporeality of its subject. In her work as a visual artist and writer, Cheryl Mukherji attempts a rewriting of the self, silence and transgenerational trauma. She does this by mobilising the objecthood of the photograph as raw material to excavate the complexity of her relationship with her mother. Peeling back layers of sentiment, grief and the weight of domestic labour; Mukherji’s work consists of a series of hands-on experiments exploring the porousness of the medium of photography.

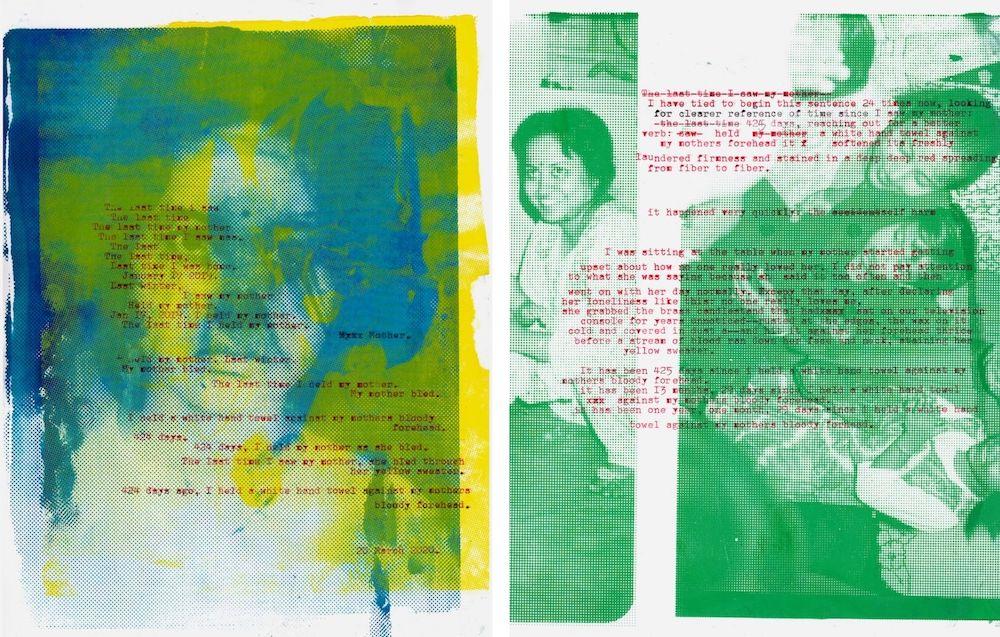

Left: The Last Time (1). (New York, 2020. Typewritten Text on Screen Print. 8.5 × 11 inches.)

Right: The Last Time (5). (New York, 2020. Typewritten Text on Screen Print. 8.5 × 11 inches.)

Mukherji arrives at photography through the textual as her primary mode of accessing memory. Being able to think in concrete words, she said, brings her to the threshold of the images she eventually makes. The forms of writing that are included in her works become meditations on the acts of rewriting, anchoring her practice. The Last Time (2020) builds a counter-archive around a specific memory of her mother and her mental illness, structured against the normative format of the family album. Using photographs of her mother that she brought with her to New York—where she lives now, after graduating from the International Center of Photography at Bard College—Mukherji screen printed these images onto paper. She then added typewritten text that recounted an incident of self-harm by her mother the last time they met. The screen printing technique allowed Mukherji to visibilise her process, likening the labour of making to the kind that maintains filial relationships. Overlaying the screen printed image with text, she reenacts the fallibility of memory. By consciously rewriting the incident as it played out in her memory, she uses repetition to map the changes in her recollections over time.

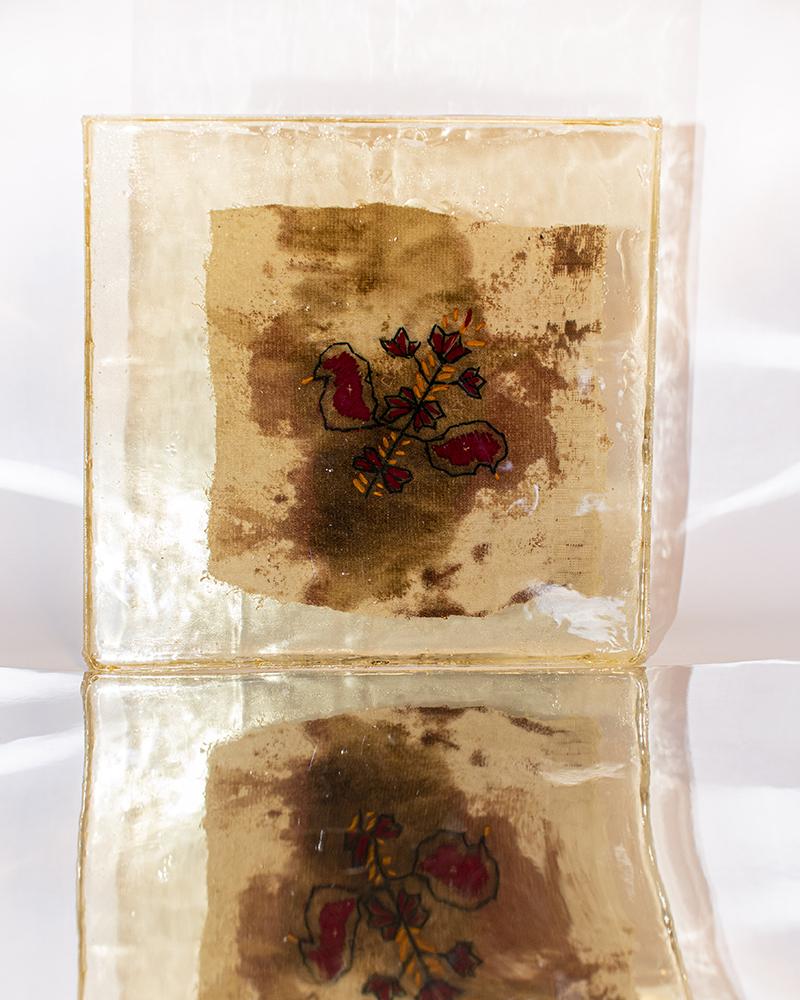

I Held My Mother. (New York, 2020. Hand-Embroidered Stained Cotton Towel in Resin. 11 × 11 inches.)

Mukherji is deeply interested in the forms of dissemination that accompany the medium of photography. Drawn to expressions that complicate acts of remembrance, her work finds ways of communicating the osmotic capacities of the photographic by intervening in its spatiality and surface. In the two works under I Held My Mother (2020), Mukherji foregrounds these by using materially pliant surfaces for the photographic, mimicking the comfort of her mother’s clothes. The first of the two works is a blood-stained towel, an object she references in The Last Time. Transforming the towel into a resin-encased artefact, Mukherji activates a certain observance of the act of reparation, manifested through the need to preserve the embodied sensation of such trauma.

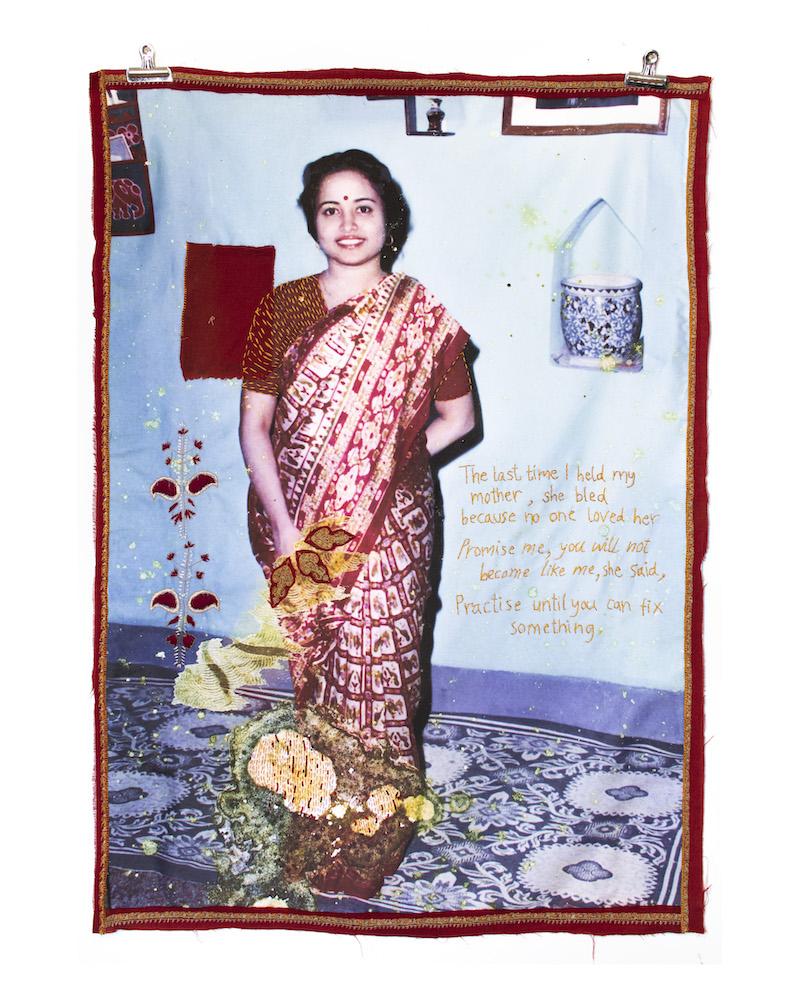

I Held My Mother. (New York, 2020. Hand-Embroidered Inkjet-Printed Cotton Lawn. 30 × 40 inches.)

The larger tapestries—extensions of her experiments with scale and printing techniques—also hint at the more primal intention of leaving a mark. Mukherji’s time spent learning to embroider is driven by a desire to reframe the skill with a subversive connotation. Her reclamation is one of whimsy, against the gendered responsibility that is bequeathed to generations of women. She envisions the act of embroidery as a haptic route to her mother. The repeated breaking and making of the surface exemplifies the solitude and loneliness that often goes unheard and unseen in familial spaces. In the light of Mukherji’s painstaking attempts to insert herself in the objects she inherits, the motif on the bloodstained towel copied from her mother’s shawl, along with the carefully embroidered text on the tapestries become citations in a series of renewals.

Left: Self-Portrait with Maa (1). (New York, 2020. Digital Photograph.)

Right: Self-Portrait with Maa (2). (New York, 2020. Digital Photograph.)

Mukherji is now keen to expand upon a conversation with self-portraiture as a means of attempting to speak about “seeing” herself in her mother. The series of self-portraits that currently exist are the start of a documentation that views her body in its bare simplicity, surrounded by images of her mother, in her apartment in Brooklyn, New York. These portraits became a self-fashioning in an unfamiliar city—wordless attempts to articulate awkwardness and derision—especially at a time when her body is at its farthest, most distant location from her mother.

All works by Cheryl Mukherji. Images courtesy of the artist.