Photographing a Chronic Catastrophe: Rearticulating Gaza through Images

Boys washing their horses in the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea—a sight that runs against normative representations of Gaza through graphic lenses. (Rosalind Nashashibi. Electrical Gaza. 2015. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

In the final post of a three-part series studying image politics in the Palestinian films showcased by Another Screen, we explore the reclamation of Palestinian representation as a form of resistance.

With its politically disputed status and long history of Israeli military attacks, the Gaza Strip—a small piece of land that is home to around two million people—has been exhausted by the international mainstream media. It has been represented as a site housing an anonymous population whose plight acquires a sameness of syntax, as visual tropes continue to be regurgitated for the Western spectator (or any eye shaped by Western visual training). The archetype of the “helpless refugee” in the circulating photographs carries affective potential, but it also activates stereotypes about the lack of agency in the Palestinian body. When the vulnerable subject is aestheticised through this lens, it is also depoliticised into a “symbol” of suffering, bereft of its singular context. In the light of this structural tendency to regulate the conditions of visibility, Palestinian artists are reconstructing Gaza through images that refuse to spectacularise the violence. Instead, they draw from personal memories of the quotidian and its attendant complexities arising from being situated in the condition of prolonged occupation.

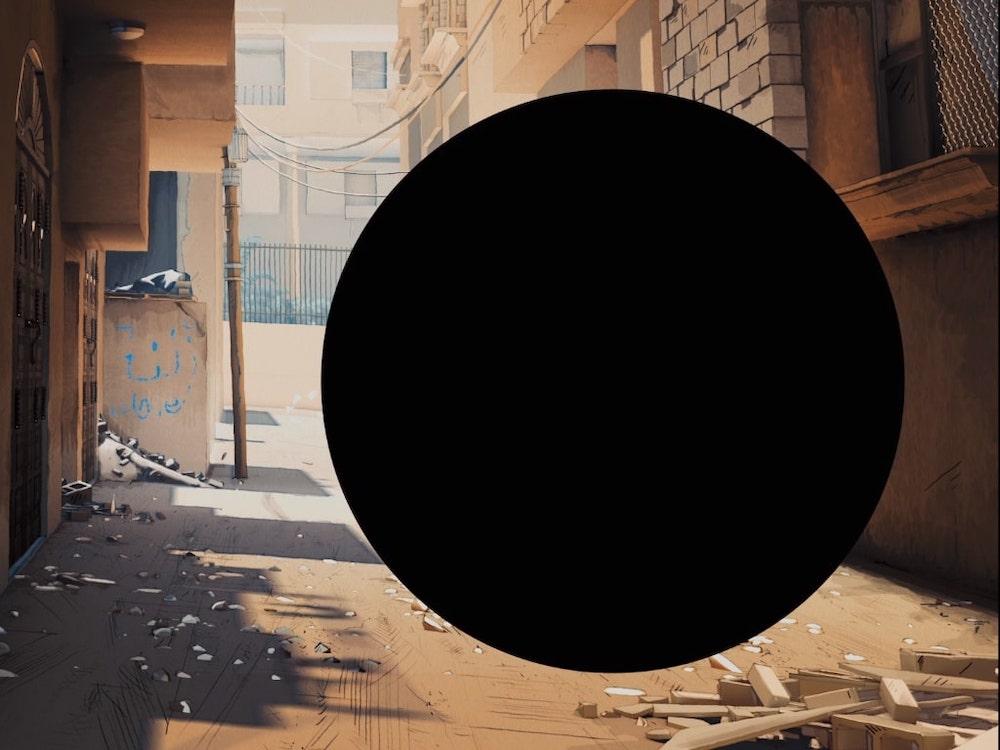

An opaque spot appears against an innocuous frame, and keeps expanding over the next few seconds. Devoid of space, time and other coordinates, the black hole enacts a perspectival shift that works to communicate the running subtext of annihilatory threat in Gaza. (Rosalind Nashashibi. Electrical Gaza. 2015. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

In Electrical Gaza (2015), Rosalind Nashashibi brings together her footage of Gaza with animated renditions of select frames (usually absent in verité́ style filming). This imparts the film a sense of childlike naiveté and curiosity—a lens she uses to view the city and its constituent lives with. A calm scape of greenery, women bathing in the sea and men singing resistance songs in a living room—these images serve to substitute the saturated depictions of Gaza as a locus of terror. Imbued with an intended sentimentality, Gaza is constructed as a speculative fiction of serene vignettes. All the while, there is a looming sense of danger; in reality, Israel controls Gaza’s maritime and airspace, which are therefore under constant surveillance and threat of (mis)use. With this knowledge, the eye views the images as charged with imminent danger. This experience is interrupted at points by Nashashibi’s own breath that registers her presence in the frame as a person and participant.

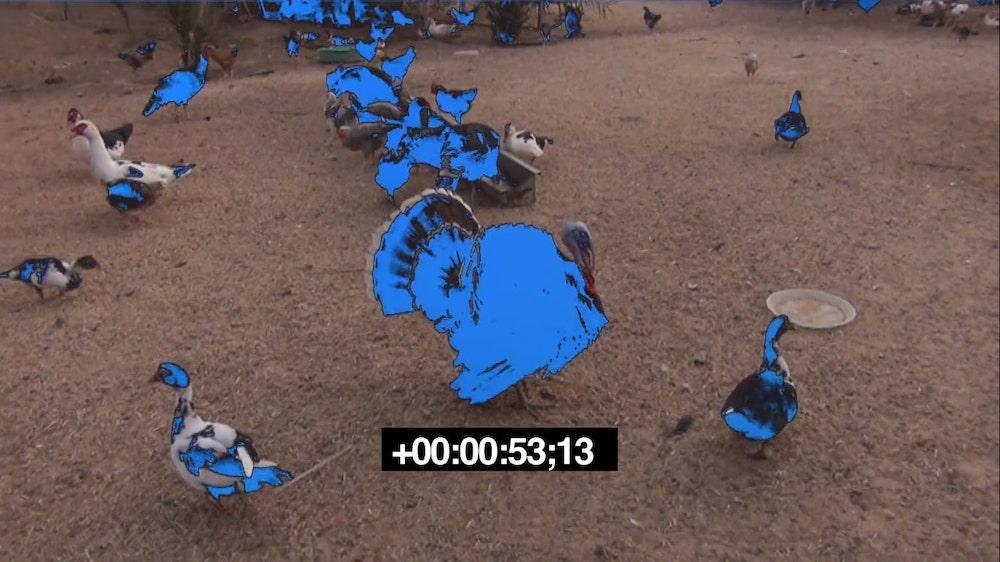

Through digital interventions, the bodies of birds and animals in the film footage is imbued with an electric blue that travels across frames, and ascribes Gazan life a porous texture. (Basma Alsharif. Home Movies Gaza. 2013. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

The mundane is explored at length in Home Movies Gaza (2013), where Basma Alsharif documents the territory in different variations of speed, colour palettes, actions and happenings. The perspective is placed on roads and in the domestic pockets of Gazan life, where the lingering hum of surveillance drones is part of the daily sonic landscape (and therefore, of the film). The repetitive destruction of the Strip has resulted in a cumulative abundance of images that could well be used interchangeably with other events of military attack in pan-Arab history. Both in tandem with and in resistance to this homogenising impulse, Alsharif rehabilitates Gaza as a regular place with people, animals and a sea, therefore, invoking a universality that strips the place of its individual context as much as it replaces its mediatic representation as a ghettoised elsewhere. In a playful amalgamation of sights and sounds, the film attempts to shift one’s gaze to the peripheries of life in a conflict zone, floating amid its pulsating reality as a disenfranchised state perpetually on what Ariella Azoulay calls the “…verge of catastrophe.”

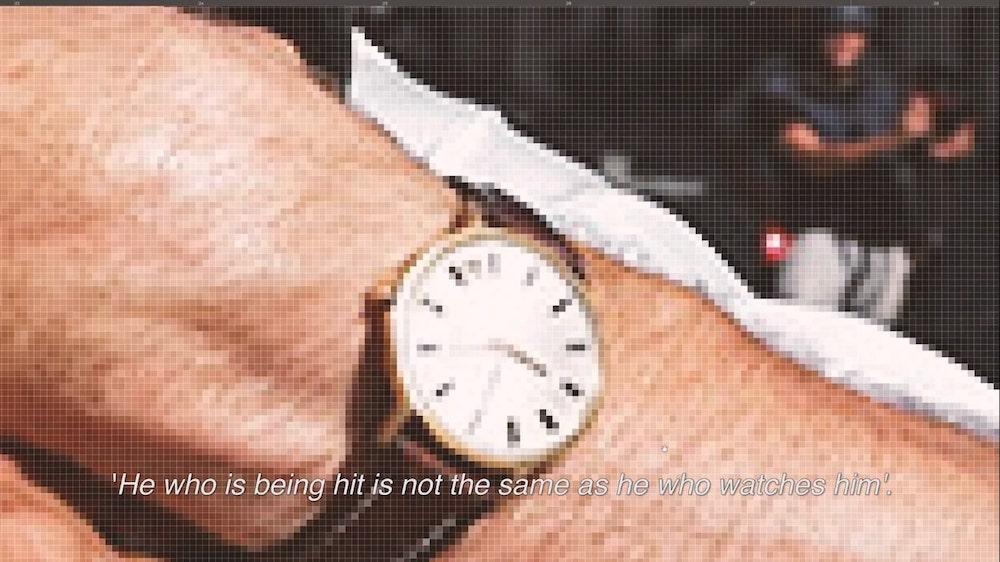

One of Toukan’s respondents, Lara Abu Ramadan, talks about how she tweeted live updates on the 2014 bombings in Gaza—from the interiors of her home—using her phone. As a techno-civilian force, social media has enabled quicker dissemination of information from the ground that has direct (and mostly unmediated) access to the end user. (Oraib Toukan. When Things Occur. 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

The contract of distance and contact operates between the photographer and the photographed/ witness and target/ empathy and fatigue. (Oraib Toukan. When Things Occur. 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

How does one photograph a chronic state of catastrophe? #GazaUnderAttack became a major hashtag following the 2014 bombing of the Strip by the Israeli military, which served to mobilise public opinion through images, live-streamed footage and first-hand accounts from the ground. Social media thus created a space for users to actively engage in a “civil contract” (Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography) of self-determined representations. Exploring this non-imperial use of photography as a militant-civil force, Oraib Toukan’s When Things Occur (2017) stitches together online conversations conducted over Skype with a range of image-producers in Gaza. They talk about the images that travelled from screen to screen during said attack, and thus the film inquires into the nature of empathy as it is digitally transmitted. As “iconic” and widely shared photographs are talked about in this desktop-documentary, Toukan slows down the concerned image by zooming in and resting on its pixel-grids. The pixel therefore becomes an entry point to a navigational image-space that goes beyond the indexical document and counters colonial optics of power.

The trope of the bloodied corpse is substituted with that of suffering as it manifests in surviving bodies, especially children. This serves as another semiotic trope used by photojournalists to stimulate interest in the face of mass desensitisation to violent images. (Oraib Toukan. When Things Occur. 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.)

The digital embodiment of death, grief and mourning enables viewing from a distance, and carries the potential to incite political action. The virality embedded in the trajectory of images from the ground points to an innate distrust in institutional representations—both within and outside the perimeters of the conflict zone. The most recent attacks by the Israeli state in May 2021 resulted in the widespread proliferation of images of violence from the Palestinian people. These simultaneously resonated with the aggravated assault on Muslim populations by right-wing fundamentalists across contemporaneous social contexts. This includes India, Myanmar and China, where the marginalised have consistently faced restrictions on mobility and resources, and are actively subjected to displacement and erasure. The mechanics of the photographic gaze have altered today, in that the subject of suffering has decidedly spoken and with immediacy. The image equals resistance, and the risk of anaesthetisation to violence runs alongside the imperative to bear witness. The image disseminated by the Palestinian photojournalist or civilian then becomes a geopolitical item of transfer, positioning Gaza as a place perpetually oscillating between institutional invisibility and digital hypervisibility.

To read the first two parts, please click here and here.