Performance and Evidence: The Heterogenous Image in Showgirls of Pakistan

In this continuing discussion on Saad Khan’s Showgirls of Pakistan, we look at how it reproduces the spectacle of 1980s Lollywood and the subsequent street and popular culture. The film uses visual and musical references from filmic montages that invite the viewer into the eclectic world of the dance performance mujra. The visual ephemera and kitsch street aesthetic that informs the film immerses us into the specific world of Punjab and Northern Pakistan working class lives. These are intertwined with media such as news reports, telephonic conversations, online livestreams, found footage etc. While the nationally mandated language is Urdu, Punjabi and Farsi are spoken for the most part in the film, attuning one to the idea of “multiple Pakistans.” Khan made a point to emphasise that this documentary shows a region of Pakistan, that is, of North Pakistan and Punjab, which has its own identity distinct from a coherent national Pakistani one.

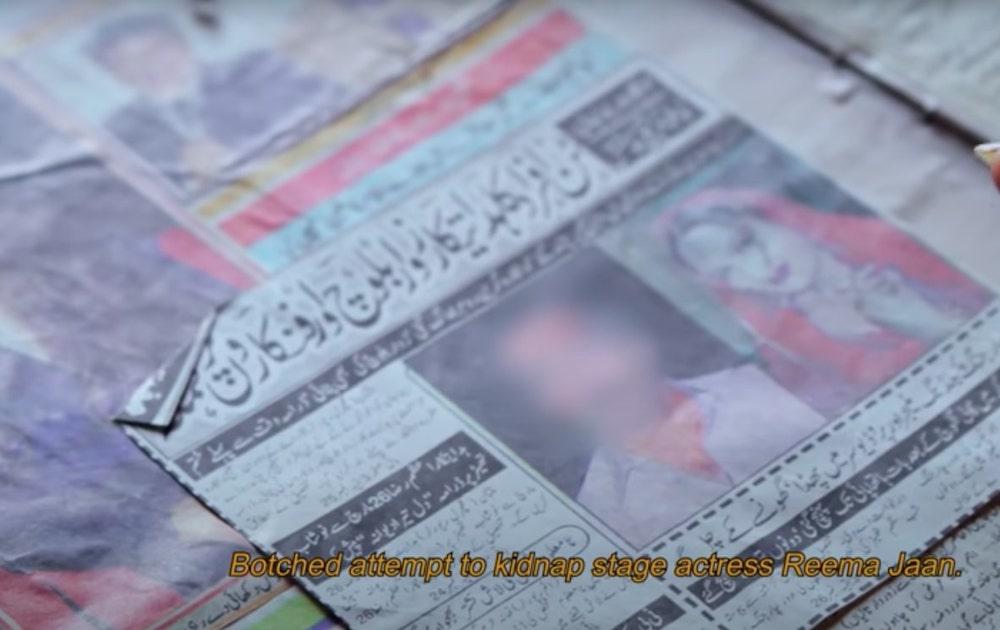

The film follows the lives of three contemporary mujra dancers living in the fringes of Pakistani society. The narrative contains archival and found footage, online livestreams, telephone conversations and other media. With the digital as an always available archive, production and documentation in this film was heavily dependent on the consideration of social media. The theme of gathering evidence as a form of safeguarding, to assist the facilitation of future justice—whether in private or in courts—runs through the film. Here, social media emerges as another form of the evidentiary—putting together testimonies, video streaming and recordings—becoming an important lens to view the documentary through.

Over a video conversation, Khan tells me about class being at the centre of understanding an overwhelming tendency towards gathering evidence in Pakistan. Those who are at the periphery of society are disproportionately affected and targeted by the justice system. The sheer volume of recordings of disputes, agreements, testimonies and other forms of evidence makes this incontestable—only a glimpse of which is captured within the documentary. This is crucial to understanding the chasm that exists between the state and the populace. As a corollary, the surveillance state produces its own documentation. The live mujra performances are visited by governmental departments, monitored, recorded and subsequently censored. The idea of the testimony and trial by the community and state appear at the forefront of the documentary.

Historically, Lollywood has largely been decentralised and deregulated. This has led to a disruption of the single nationalist image—unlike most other film industries, which are a product of the nation-state, or at least are informed by them. Throughout the documentary, Lollywood is used as a point of reference in the production of street culture. For instance, the “rape and revenge” theme, a filmic trope and subgenre of horror and thriller, is used to create a certain effect. The wrath of the mujra dancers is represented as they spit metaphorical fire or invoke Allah as they swear that they will only be judged by God and not human-made institutions.

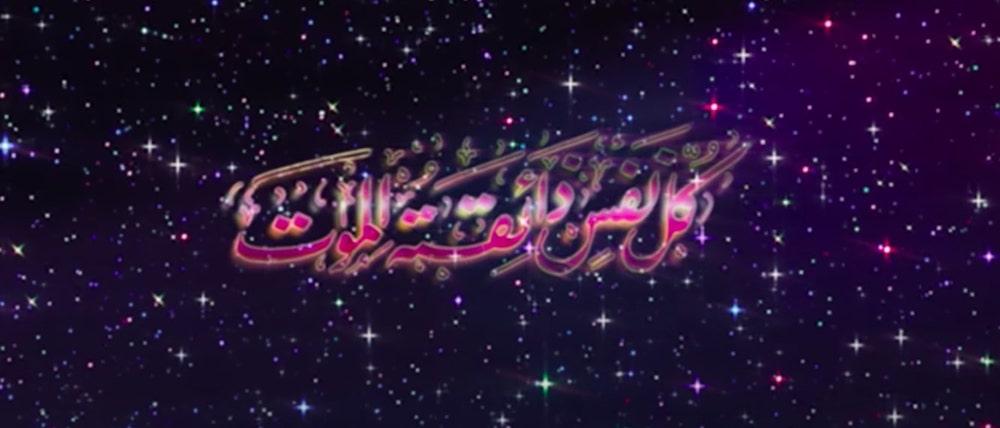

The initial title sequence of the film begins with a bokeh sky of stars, reminiscent of low budget VFX. Over this, a booming voice enters—similar to public street announcements—reciting a Quranic verse. Glittering letters—mirroring the luscious bodysuits adorned by contemporary performers of the mujra—in campy Urdu calligraphy, fade in to reveal the title of the film. This sets the tone for the aesthetic takeover of the senses that is in store with Showgirls of Pakistan.

We are introduced to the glamorous Afreen Khan—one of the main characters in the film—via her crooning, baby-talk voiceover addressing a live audience. As the video snippets of her manicured and playful toenails are shown, we are offered an insight into the well-honed personality that she has cultivated for her fans on a live-streaming platform. We catch a glimpse of her face as she blows smoke rings from a hookah pipe. Through a montage of Afreen’s dance routines, we are familiarised with her oeuvre.

Over time, mujra dancers have been able to utilise new technologies, from VHS and VCDs to the current boom of social media and live-streaming platforms. Since the influx of Chinese phones into the Pakistani market, the purchase of smartphones with pre-installed streaming applications has become a widespread practice. Bypassing statewide cultural censorship, to a large extent, social media allows for the creation of a safer space for women and marginalised genders to occupy. The prevalence and ubiquitousness of social media has allowed women to obtain livelihoods in a safer manner via the image creation and projection that they maneuver, as can be seen in Afreen’s playful interactions depicting her stylised personality.

Each mujra performance in public theatres begins with the national anthem, a reminder of the looming surveillance and an enforced piousness. This can be read as parallel to the recordings of Quran verses playing at the beginning of X-rated Lollywood films from the 1980s onwards. Khan speculates, in our conversation, that these might have been to “…soften the censors.” We see glimpses of street visual culture such as banners, posters, larger-than-life cutouts of film stars and celebrities, stickers and other ephemera. These are visible in various shops as well as inside Afreen’s dressing room. The sets on the theatre stage are also low-budget and colourful as they imitate Mughal dressage and palaces. This informs a heterogenous survey of cultural production, where “vulgarity” in image—as in appearance and sexuality—is classified by middle-class sensibility.

Where the state and its actors are active agents of violence, the idea of “facilitating justice” becomes a point of reckoning within the community. Uzma Khan, another main character in the documentary, records entire conversations—where there is a mix between private and professional—with her manager-turned-boyfriend Imran who is out to set hitmen on her. It was through these recordings that Khan was eventually able to disentangle the complexity of the relationship they shared. The idea of documentation in the face of violence and distrust—of individuals or the state—is one of the crucial themes highlighted in the film. Documentation in the form of recorded calls in tandem with the possibility of archiving content through social media, creates an enormous repository to draw evidence from. Khan’s work thus opens out questions about the process of archiving. He challenges what historians might privilege from contemporary cultures by moving away from the wider narrations around the nation-state and a uniform idea of Pakistan.

All images from Showgirls of Pakistan by Saad Khan. 2020. Images courtesy of the artist.