From Nudity to Obscenity: An Anecdote by Sunil Janah

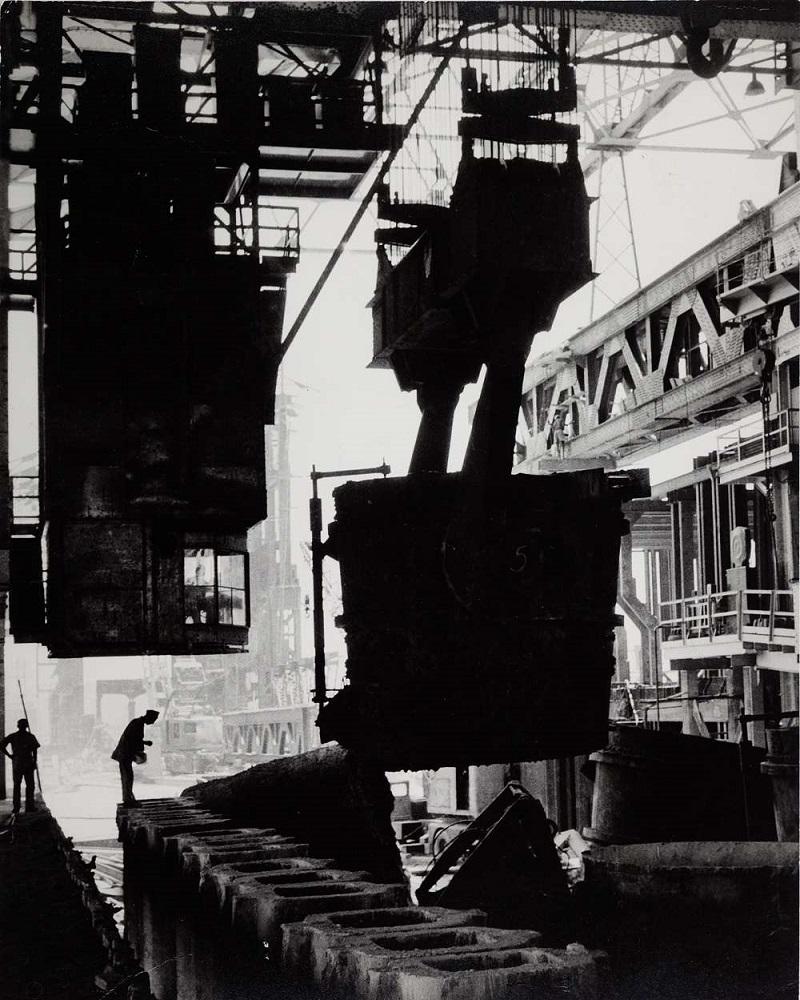

Tata Iron and Steel Works, Jamshedpur, late 1950s. Photographs like these—perhaps among Janah’s most famous ones—also faced potential censorship in the political-bureaucratic complex of postcolonial India. If the country went to war with China, a commissioned photographer like Janah could have his rolls of film—depicting external views of factories (he calls them the “new temples” of India)—confiscated by the Defence Ministry without any explanation. (Image courtesy of Chatterjee and Lal.)

In this continuing translation of an interview between Sunil Janah and Siddhartha Ghosh, we take a closer look at the eminently frustrating nature of state-bureaucracy with regard to process of intimate artistic creation. Janah’s encounter highlights the dangers that the intimate act can invoke in the mind of a censorious, paranoid and morally enervated nation-state obsessed with policing the boundaries between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” forms of nudity. This is reflected its continuation of colonialist investments in categorising difference along lines of tribes, castes and regions. In the latter respect, one would have to move away from a history of artistic creation and focus, instead, on an abortive history of non-production. Here, the failure/impossibility of a project is as much a symptom of a repressive state as a failed contract for visualising personal intimacy, in the public sphere of a diverse, secular nation.

The question of nudity was haunted by the concept of obscenity and national identity. Certain groups of people could be shown to be exotic and nude—adding to an ethnographic archive, while other, more "normative" bodies could not be shown to be nude publicly without risking censure.

In response to a question probing the misappropriation of his work by curators, publishers and exhibitors, Janah tells the story about Indian customs restricting the passage of his photographs (for exhibition at the Festival of India, in London, 1982) on suspicions of obscenity. It is part of a larger theme in the interview, which Janah addresses at considerable length, critiquing the bureaucratic high-handedness that allows a lot of artworks and artists’ careers to fall through the cracks due to official neglect. His famous photographs of tribals—seen by customs officials to be “obscene” for their depiction of unclothed women—gets resolved by the intervention of the highest public official in the land, the prime minister herself, Indira Gandhi. But Janah had other concerns as well:

Sunil Janah (SJ): I have not mentioned one other thing. Among the photographs that were stopped by the Customs’ agents, there were a few nudes which I have taken in my lifetime—every photographer does that—and those they labeled with “extreme obscenity,” because, obviously—they were not tribals—they were of civilised women of many nationalities. But the trouble with those photographs was this: I had not used any professional models. Mostly they were of my wife, my friend’s wives, or my women friends—so of course, when they held those back, I was struck with terrible anxiety. After all, they knew I would not print those, they had enough trust in me to undress before my camera knowing that they were in safe hands! They did not know in whose hands these may fall one day, or what might happen with them, subsequently—among them were well-known dancers, society ladies, married to someone respectable—after all there are so-called tiers of responsibility. When they got those photographs taken, they did not think about the damage to their respectability, because they did not care about such things then. But who knows what they might think today! And they would be shocked and terrified. So, it was not just the photographs of tribals but a few studio nudes. Customs had then arranged for these nudes to be seen by, of all people, Indira Gandhi—after she had summoned them. I wrote to her, saying that I was distressed to think that some of these photographs of private persons—of people and friends who were kind enough to give me the privilege of photographing them—should be seen, of all people, by the prime minister of our country! I hoped that she would appreciate that every artist would do certain amount of nudes in his lifetime because he has to know human figures, and the human body is one of the most beautiful objects of art… I have no shame that I took them but I was concerned about their misuse by others…

Then they called an art expert from Customs. You would not believe, I have had 200 pictures, every one of them stamped “not obscene”! Every photograph was officially stamped and signed off on. They did not understand the difference between eroticism and obscenity. After all, there is a certain amount of eroticism in all art—without that no art can survive. To take glory in the human body is an artist’s privilege.

Janah’s book was one of the most important projects of visualising tribal identity and livelihoods in India. He also took photographs of Verrier Elwin and encouraged, like the anthropologist, a participative approach rather than distance or uninvolved “objectivity.”

All images by Sunil Janah.