Post-Industrial Loneliness: Through the Lens of Cat Sticks

Speaking of his practice in a telephonic conversation, the director of Cat Sticks (2019), Ronny Sen said: “Whatever is problematic or fascinating in the present is a photograph for me. And whatever belongs in an unresolved past is a film.”

Cat Sticks follows disparate groups of smack (an adulterated form of heroin) addicts over one fateful night, capturing chance encounters between friends and drug users looking to score. The film opens with a group of friends occupying an abandoned Kingfisher aircraft on a particularly rainy night. Bold letters display “KING,” while the rest of the name has been stripped of recognition. The context of the film allows us to imagine the aircraft as a symbol of a defunct safe haven against the throes of rapid industrialisation and disillusionment.

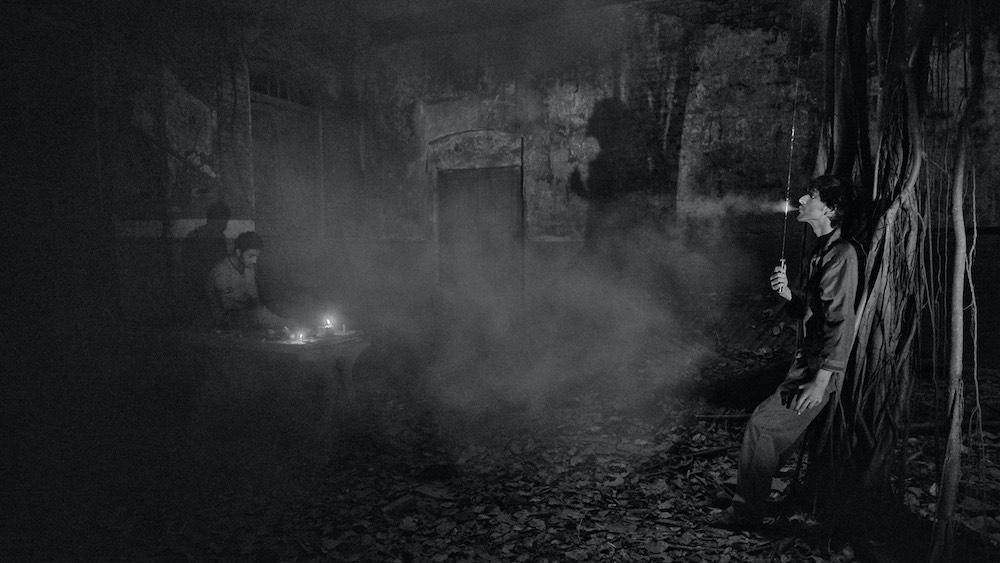

Still from Cat Sticks.

Inspired by the filmmaker's childhood in the cosmopolitan Salt Lake or Bidhannagar in Kolkata, the landscape of the film echoes this sense of an unresolved past. Developed between the 1960s and 1980s, the salt lakes in the area were pumped dry and refilled with sand from the riverbed of Hooghly, in a land reclamation project. It was built to create residential areas for migrating peoples from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) after the partition of Bengal in 1947, as the city could only expand in the north-to-south direction, with Hooghly on the west and marshes on the east. The urban middle-class dream of seamless settlement and expansion was embodied in this new project.

In the following interview, Sen speaks to Sukanya Deb about his film, its context and raising awareness about addiction.

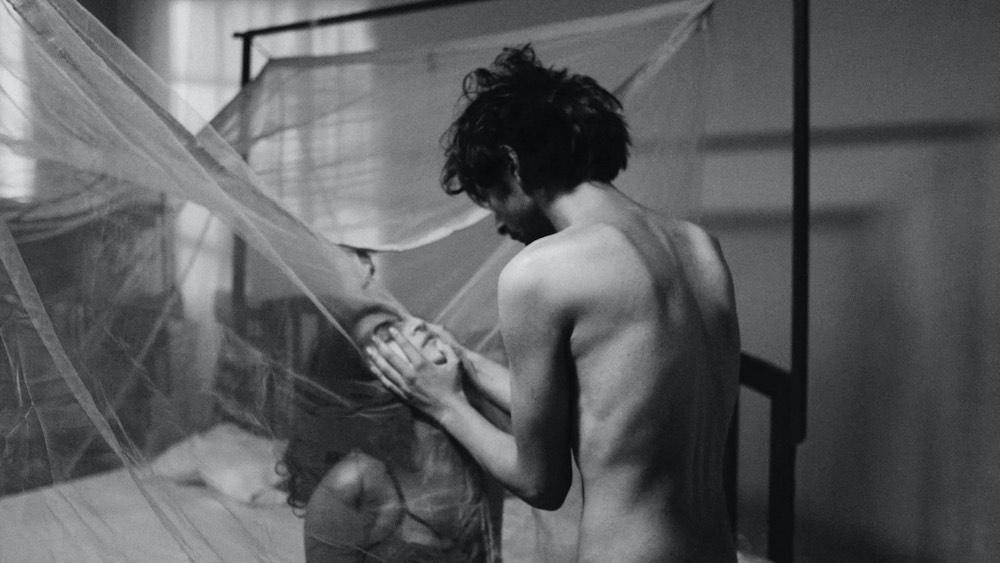

Still from Cat Sticks.

Sukanya Deb (SD): You mention growing up in Salt Lake, with its history of land reclamation and development in the 1960s initiated by the chief minister at the time, Bidhan Chandra Roy. How do you see Cat Sticks within the framework of the industrialisation of Kolkata?

Ronny Sen (RS): We grew up in the shadows of romantic ideas about the industrial town. Growing up in Kolkata, we witnessed factories being shut down one after another. We were aware of these issues of land, labour and growing up in the backdrop of a failed Nehruvian dream.

If you notice, in the film you will never find a Howrah Bridge or a College Street, Maidan or Victoria Memorial. The architecture of the city is shown in a way that reflects other small towns with a factory in the neighbourhood that has been shut for many years, parallel to other places across the world like Ukraine, Belarus or Detroit. This gave me the freedom to leave Kolkata and read about similar places that share a kind of post-industrial wrath and loneliness. Through the film, I try to suggest where it is that addiction thrives. An addict is a person who is an addict all the time. It is an incurable disease that they have to live with their entire lives. I was interested in the everyday nature of an addict’s life.

Still from Cat Sticks.

SD: Since the release of Cat Sticks in 2019, you have been involved in raising awareness around addiction, through social media and interviews. In past interviews you have also mentioned a personal connection with the story. Could you speak to that?

RS: This is a story I had always wanted to tell. I had spoken to my friends about the atmosphere when we grew up in Salt Lake of the 1990s through the lens of addiction. Since I knew this world well, I was confident in telling this story.

In India, we do not have the institutional mechanisms to address addiction, so we try to do some basic course correction. In 2019, some of my friends founded an organisation called Alliance to Protect Drug Users to inform people about the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, 1985 and its repercussions, and why it remains ineffective against the misuse or abuse of drugs in society.

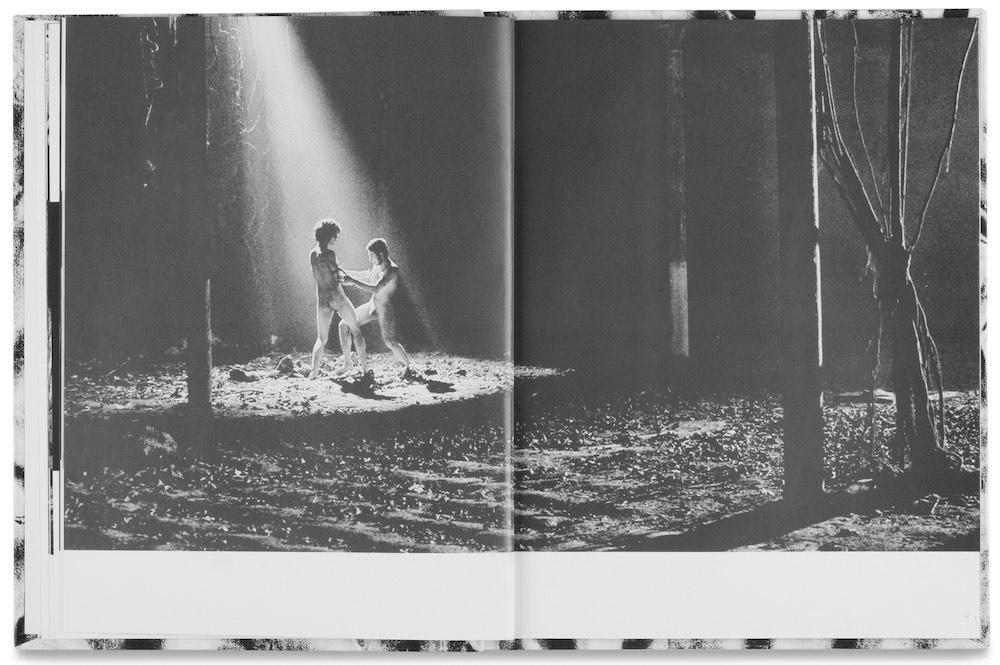

Spread from a photobook accompanying the film showing a still from Cat Sticks.

The people of this region have been doing various substances for centuries before alcohol was brought in by the British as a commercial product. The Bombay Presidency introduced the Abkari Act in 1878, which was designed to discourage home-brewing, fermenting or transportation of alcohol without a license. Industrial scale alcohol production was brought into the country through Indian-made-foreign-liquor. The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission of 1895 was created under the East India Company because the British saw people in India smoking ganja or weed. Home brewing of country liquor continued as a way of life in areas where industrial alcohol could not reach because of the lack of infrastructure. Slowly, our morality and desire were manufactured so that drinking alcohol was socially accepted, but smoking ganja was not.

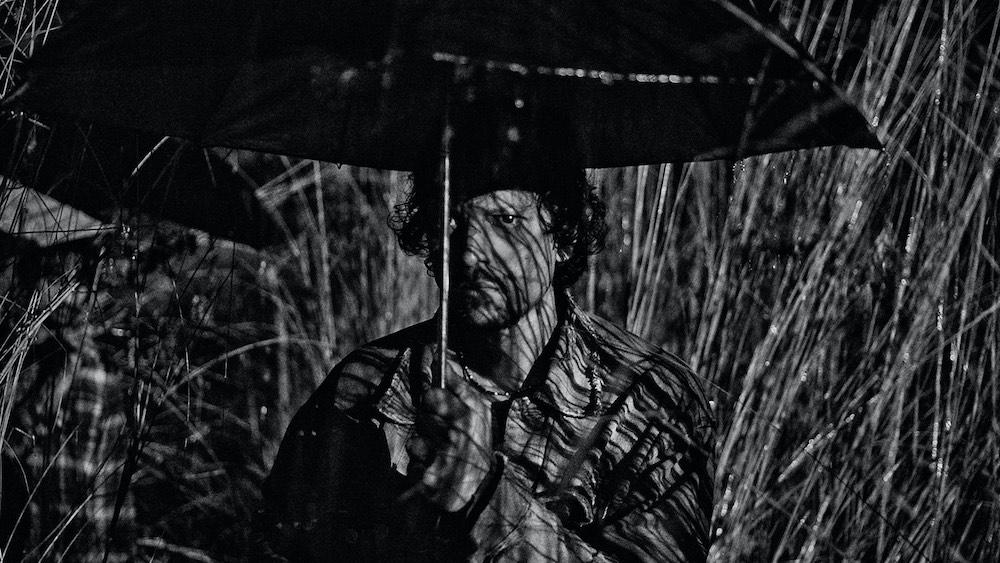

Still from Cat Sticks.

SD: As you say, there were no chemical drugs in India fifty years ago. This also makes the discourse around it very new.

RS: In India, if you look at it from the point of view of the law, drug addiction has not been defined. Incarceration, rather than treatment and care, has been our answer so far. Addiction treatment is looked at by the Ministry of Social Welfare not the Ministry of Health. The desire in people to alter their consciousness is as fundamental as their desire to eat, sleep or have sex. Here, the substance is not of importance. That is why in certain support groups it is said that “We are powerless over addiction” instead of naming the specific substance.

All images by Ronny Sen. 2019. Images courtesy and copyright Craigmore Films.