Encountering Violence: An Array of Loose Documents in 1528

In July 2016, marking a milestone judgement for the case of Extra-Judicial Execution Victim Families Association Manipur (EEVFAM) vs. Union of India—popularly known as the Manipur Encounters Case—the Indian Supreme Court stated that armed forces cannot claim blanket immunity from prosecution. As an extension of this, criminal proceedings can be made against armed forces personnel in instances of excessive force resulting in the death of any person. This judgement came in light of the case by EEVFAM highlighting 1528 cases of extra-judicial killings that have been falsely characterised as “encounter” killings, committed by armed security forces in Manipur between 1979 and 2012. The judgment was received with much controversy from army personnel, 355 of whom petitioned against the alleged “dilution” of powers.

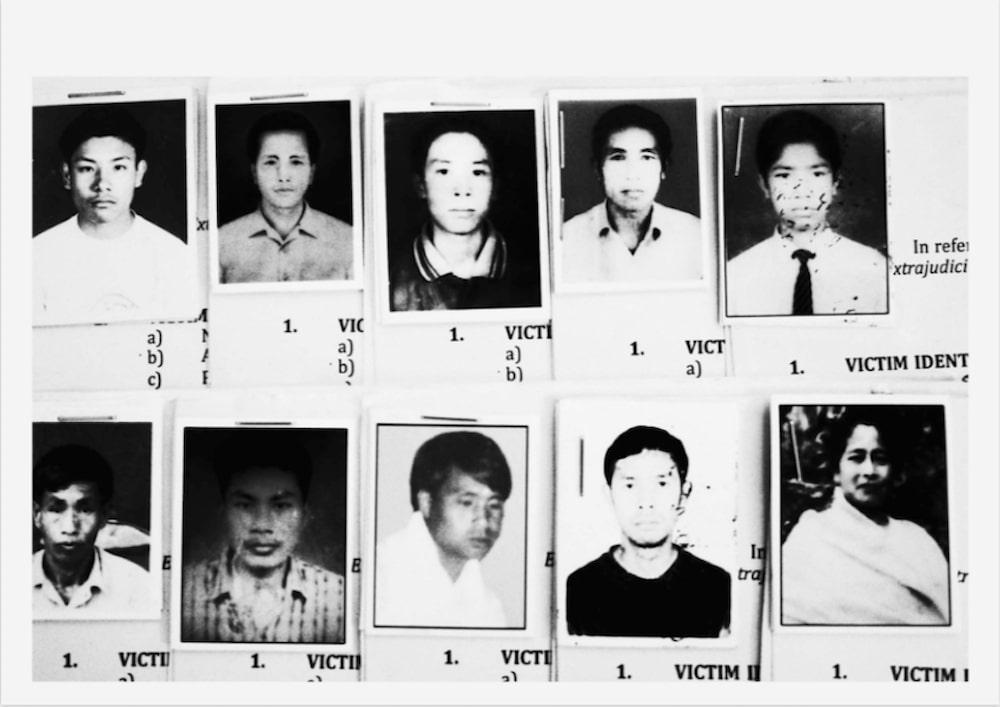

Malom Massacre Victims, EEVFAM Archives.

In October 2016, photographer Rohit Saha journeyed to Imphal, Manipur, embarking on a project that would result in the photobook 1528. Initiated as part of his graduation project under the aegis of the National Institute of Design (NID), the photobook was published by the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts under the Alkazi Foundation Photobook Grant in 2017. The premise for Saha’s project was to follow Irom Sharmila, the “Iron Lady” of Manipur, on her election campaign trail for the first hundred days, with the then newly formed People's Resurgence and Justice Alliance (PRJA). Sharmila had been on a sixteen-year-long hunger strike against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act after the Malom Massacre in 2000—which involved the killing of ten civilians standing at a bus stop—perpetrated by the Assam Rifles, an Indian paramilitary force in the state. Saha happened to reach Imphal, the state capital, the day before Sharmila was to publicly announce her party and candidacy. During this period, the photographer also volunteered with EEVFAM to help digitise their records, much of which consisted of disordered loose sheets and photocopies in folders.

Imphal East. (Rohit Saha. Manipur, 2017.)

The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) 1958 allocates “special powers” to the Indian armed forces, military or paramilitary, granting them the authority to arrest without warrant, to enter and search any premises, and, in “special circumstances,” to use lethal force, under the claim of maintaining public order in claimed "disturbed areas.” The “disturbed area” status has been applied to the state of Manipur since 1980, periodically extended. In conversation with friends and locals, Saha realised that the Malom Massacre—while it occupied a certain visibility in mainland India—was simply one day in the larger history of violence in the region. It was a daily threat, with mostly young men being picked up and/or brutalised in Manipur, a state caught in the crossfire between insurgency and extra-judicial brutality. In a conversation with me, Saha described the crossfire between the Armed Forces and insurgents as being an “infected cycle.”

Victim’s Sister. (Rohit Saha. India–Myanmar Border, 2016.)

Carrying a small-format camera that allowed him to blend into his surroundings, Saha pieced the project together through volunteering for EEVFAM and conversations with people in the city. 1528 is one of the products of this journey, in which he collated two parts of the three-part project into the photobook, drawing from evidentiary files with the organisation and his own revisitation of sites and people who had been affected by the Malom Massacre, as well as in the thirty-three years of violence. Saha told me that once a man is deemed to be a “terrorist,” the family loses all infrastructural amenities and public safety nets that are in place, pushing them towards ostracisation by the state. While carefully going through the files, a question occurred to him—had he been in the same situation, who would be writing about him? Saha also spoke about particular incidents: of a woman who filed a report when her husband went missing after going to get paan in the night, only to find out via television news that he had been killed in a supposed encounter.

Left: Imphal West. (Rohit Saha. Manipur, 2016.)

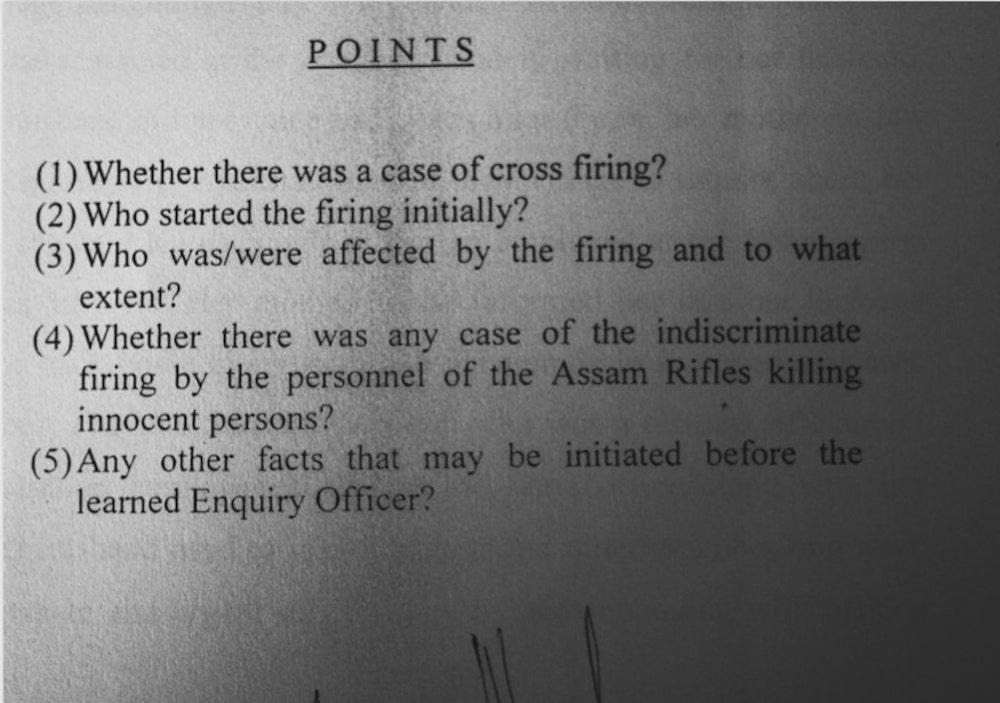

Right: Evidence, Data Collection Form, EEVFAM Archives.

1528 is presented in high-contrast pages that seek to replicate the photocopied visual of the files that Saha handled as part of EEVFAM’s archive—which included testimonials, FIRs, official documents, news reports and photographs—typically black-and-white. Following the same aesthetic, Saha recreated photographs of places where incidents occurred in the past and documented the surviving family members of victims of police and (para)military encounters. The title of the photobook is paradoxical, as it produces a “record of no record”—as Saha said to me in a telephonic conversation—or a partial record of extrajudicial killings. This includes all the evidence that the organisation EEVFAM had been able to document and find testimonials for, as presented to the Supreme Court, while they remain beyond the scope of institutional recognition. The convoluted nature of witnessing, testimony, documentation and records is apparent in a state where the police paired with armed forces are a threat to the general populace. The high contrast photographs appear as images of the night, electric with tension and fear.

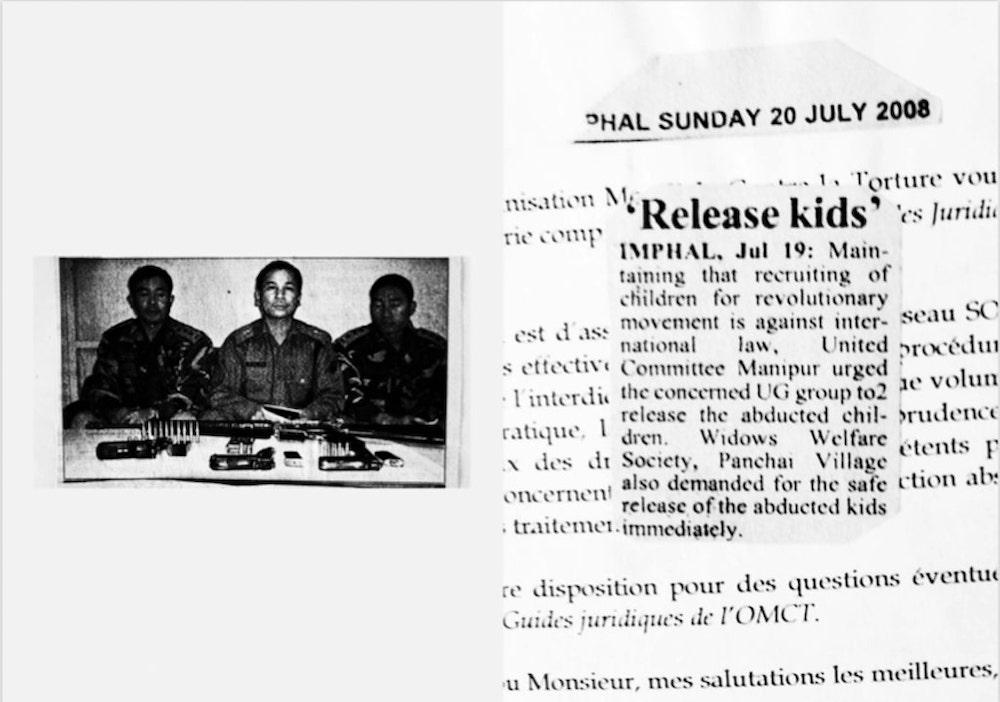

Left: Evidence, Unknown Newspaper, EEVFAM Archives.

Right: Imphal Sunday, 20 July 2008, EEVFAM Archives.

The photobook was produced to be the same size as a newspaper, placed in a cover that resembles a brown investigation folder and held together by an elastic band. The pages are left as loose spreads without page numbers such that they can be taken out, displayed, rearranged, and kept back in—recreating the lack of linearity that Saha witnessed as he scoured through the folders for sequences of events. In a way, what occurs in Imphal is circular. There is an act of searching that Saha tries to replicate through the back and forth between the printed non-sequential photographs and the list of references.

Evidence, Data Collection Form, EEVFAM Archives.

When it rains in Imphal, the city floods, as it is a valley compared to the other districts in the state that are atop hills. While Saha was there, the rain led to families taking out their photo albums from underneath their beds and showing them to him. The family albums bring together the other, happier memories associated with the times of unrest—of celebration, joy, playfulness and more. This part of Manipur is not witnessed by the outsider. Saha took photographs of the albums in the hope of returning to the state once again, and continuing his investigations as part of the project in the future.

All images from 1528 by Rohit Saha. 2017. Images courtesy of the artist and EEVFAM archives.