Aspiring to a Nation-State from the Borderlands: Traces of the Personal in the Lhamo Tsering Archive

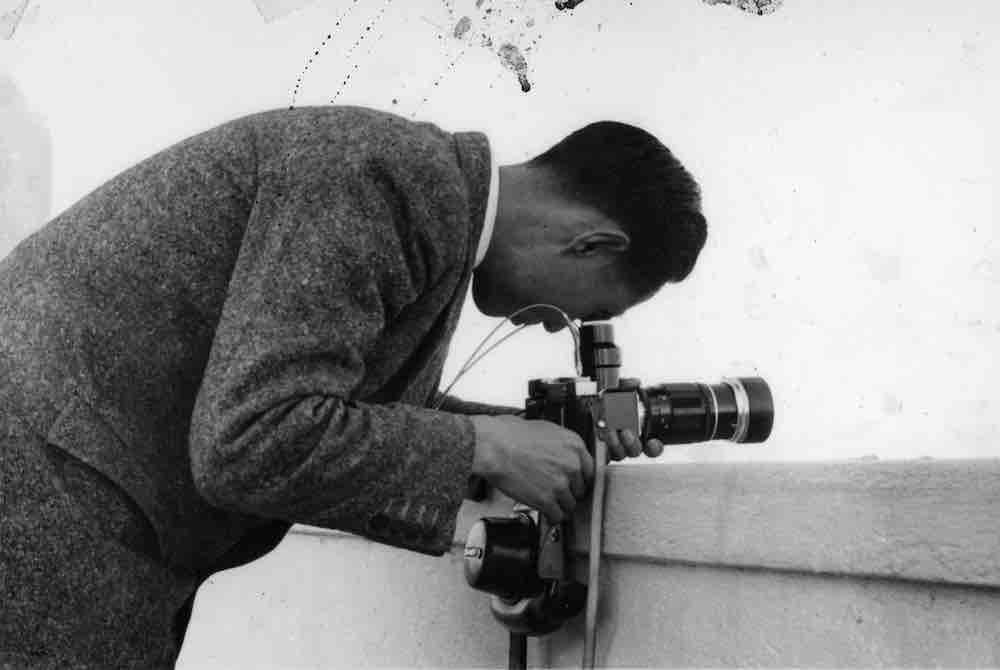

Lhamo Tsering with a camera. (Darjeeling, circa 1960.)

In a black-and-white photograph, a man peers into a camera. Equipped with a zoom lens and a remote trigger release, the camera rests on a ledge pointing off-frame into an overexposed white background. The man’s hair is meticulously combed and he wears a woollen blazer. This is Lhamo Tsering. While the previous piece looked at the Lhamo Tsering archive to narrate a lesser-known history of the Tibetan struggle and of anti-colonial movements in the Cold War world, this post focuses on Lhamo Tsering’s personal history as it is reflected in his archive. It represents a peculiar itinerary that led from the borderlands of north-eastern Tibet to Nanjing, Kalimpong, Colorado, Mustang and finally Dharamshala. This is a personally important history for me, as Lhamo Tsering was my grandfather, and the custodians of his archive, Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, are my parents. In addition to the archive’s existence as a record of the Tibetan struggle, it is also a record of how larger historical processes are produced by—and in turn produce—new trajectories for people’s lives as well as how the histories of nation-states intersect with personal histories.

Lhamo Tsering was born in the borderlands of north-eastern Tibet near Kumbum monastery, close to the Dalai Lama’s homeland. This was an ethnically diverse region that for centuries had been beyond the reach of the Lhasa state as well as Chinese authorities. In 1997, Sarin and Sonam documented their travels to Kumbum in their film A Stranger in My Native Land, where they found a homeland that was deeply colonised by China. But in Lhamo Tsering’s youth, this area was controlled by regional Hui (Chinese Muslim) warlords and its inhabitants spoke—and continue to speak—Siling key, a tongue that is unintelligible to speakers of Central Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese (though it is customarily classified as a dialect of the latter). The Tibetan nationalism that Lhamo Tsering committed himself to as an adult would have scarcely been conceivable here in his childhood in the 1930s and 1940s.

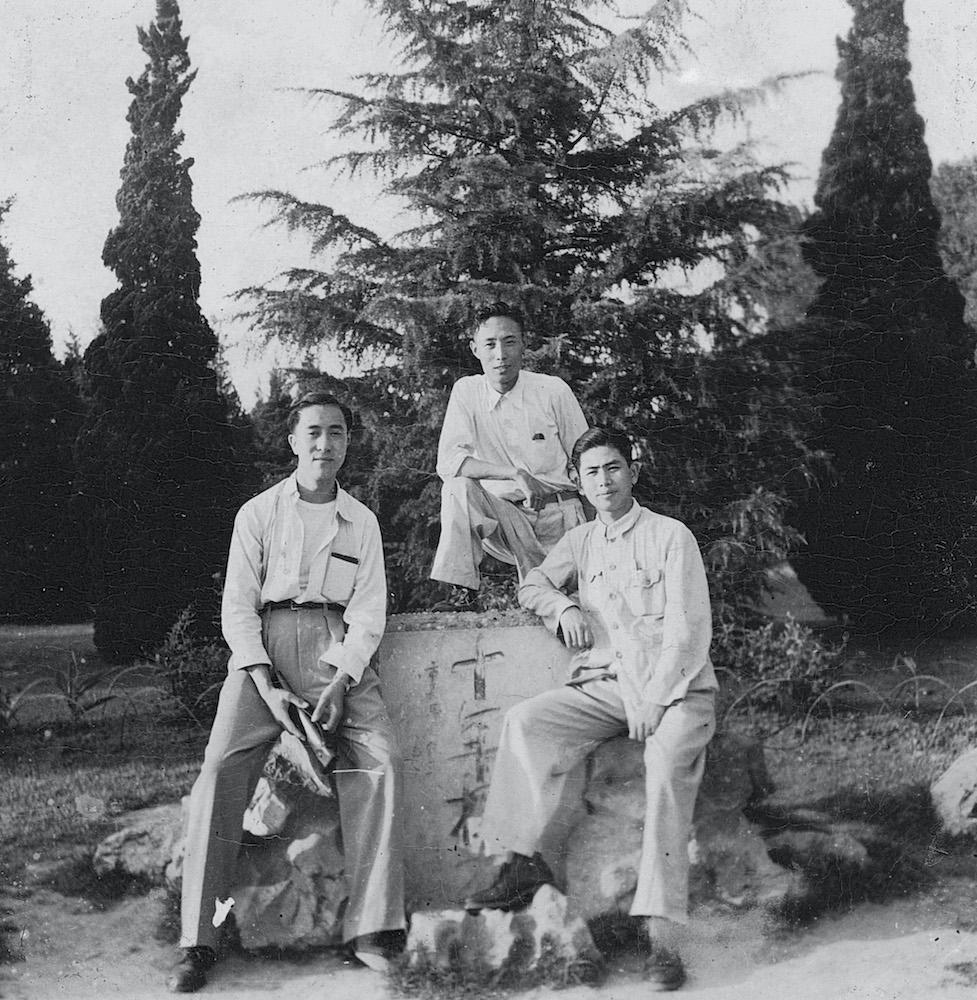

Lhamo Tsering (middle) with Gyalo Thondup and a fellow student. (Nanjing, circa 1947.)

It was in China—where he spent time as a student at the Institute for Frontier Minorities in Nanjing, surrounded by other ethnic Tibetans from the border regions of Kham and Amdo—that Lhamo Tsering began to see himself as part of a nascent national project. This was spearheaded in part by his fellow student and lifelong associate Gyalo Thondup, the young Dalai Lama’s older brother. A group portrait from this period shows three young Tibetan students at Nanjing: Lhamo Tsering and one unknown other positioned respectfully apart from Gyalo Thondup. During the Chinese Civil War, Lhamo Tsering escaped with Gyalo Thondup to Kalimpong in India. A town where Tibetan traders had long maintained a significant presence, it was one of the major sites from which a Tibetan national collectivity was being imagined. In the subsequent years, as Tibet fell to an invading communist party, the Lhasa state gradually collapsed. In 1959, when the Dalai Lama escaped to India, Lhamo Tsering committed his life to a new, independent Tibetan nation-state.

Classroom at Camp Hale, with CIA trainer Ken Knaus and interpreter Thinley Paljor. (Colorado, 1959–64.)

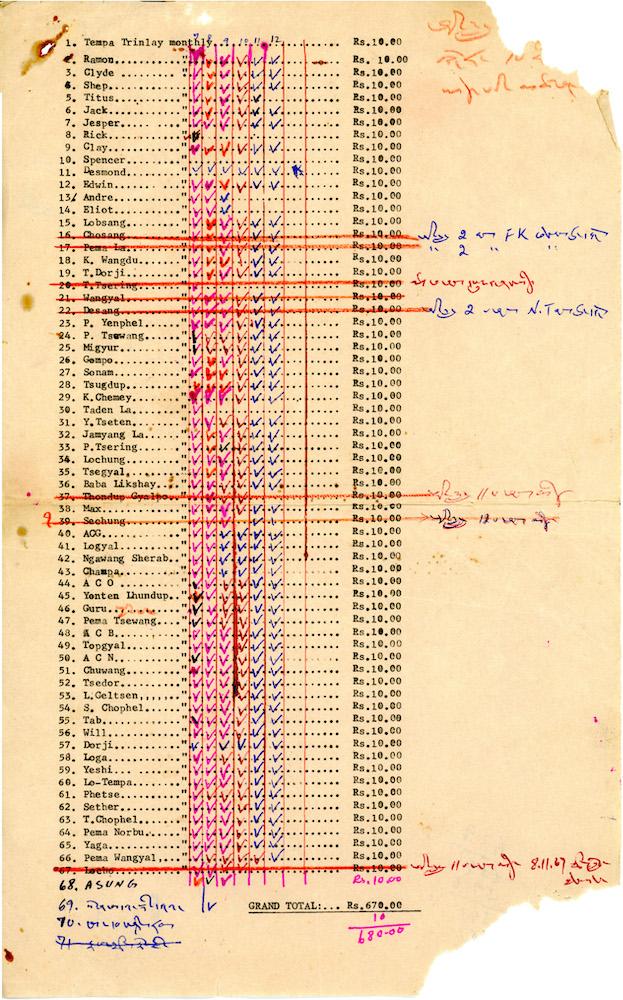

Monthly salary records. (Mid to Late 1960s.)

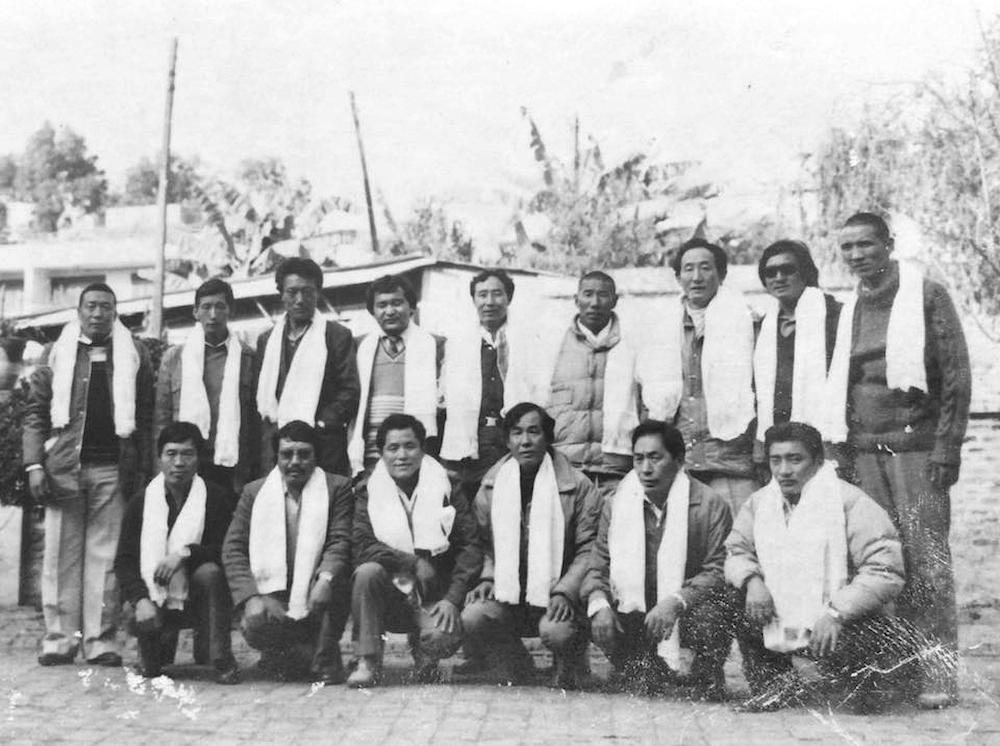

The Tibetan exile movement’s association with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) would take Lhamo Tsering to Colorado and Washington DC, where he was known as “Larry” by his CIA contacts. As a liaison between the CIA, the Indian Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) and the Tibetan exile establishment, he oversaw the gathering of intelligence from occupied Tibet and was also responsible for the management of the Mustang Resistance Force. In 1974, during the dramatic collapse of the resistance, he was arrested by the Nepali state and incarcerated in Kathmandu for seven years. After his release, he served as a Minister in the exile government, while continuing to oversee clandestine activities in Tibet. During this trajectory, Lhamo Tsering kept detailed records and amassed the archive that today bears his name. Together, these personal records index the extraordinary historical convergences that enabled the aspirations and struggle for a modern Tibetan nation-state.

Lhamo Tsering (top middle) after release from prison. (1980.)

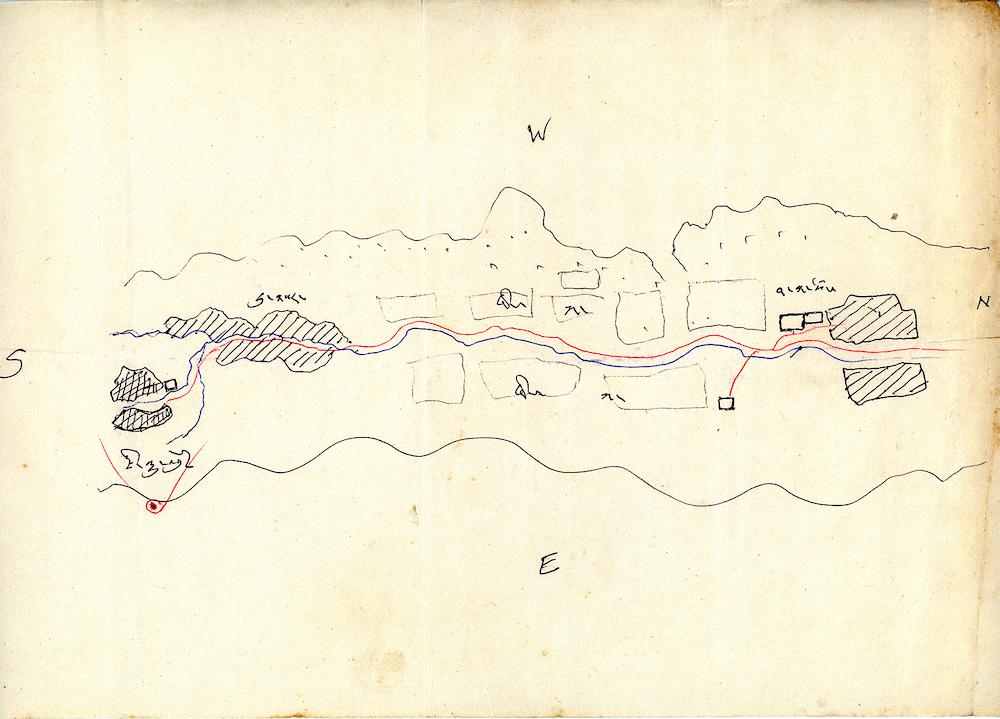

The importance of actors from the contested borderlands of Kumbum—Lhamo Tsering but, more centrally, Gyalo Thondup and the Dalai Lama himself—to the movement for a modern Tibetan statehood from exile is particularly intriguing and worth remarking upon. The exhibition Shadow Circus ends with a map of Lhamo Tsering’s home village, Nagatsang, which was drawn from memory in his last years. This object—accompanied by a video in which he describes the drawing—forms a curious appendix to the archive, pulling together his cartographic training from the CIA with aspirations for a homeland that has always been a borderland. Looking through these personal traces within this archive helps us centre the often hidden, usually deeply personal work of translation and brokerage—the cultural competencies of the borderlands that undergird more visible aspirations towards statehood.

Map of Nagatsang, drawn from memory by Lhamo Tsering. (1995.)

More details of Lhamo Tsering’s life can be found in the book Shadow Circus, by Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam and in Jamyang Norbu’s entry on him in the biographical encyclopaedia The Treasury of Lives.

All images from the Lhamo Tsering Archive. Images courtesy of Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam.