Desert of the Real: Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar

Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Safar-e Ghandehar (Kandahar, 2001) was shot in the borderlands of Iran and Afghanistan, using a semi-fictitious trope to represent the reality of the landscape. It was motivated by the need to visualise Afghan reality in a new, radical manner of empathy. However, the film was quickly absorbed by the force of events produced by the American reaction to the 11 September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, New York, which took place only a few months after the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Layers of American and global interests obscured the reality of Afghanistan, whose true image as a land devastated by the brutal takeover of the Taliban was quickly concealed under a veil of war propaganda.

Makhmalbaf’s films on Afghanistan— including The Cyclist (1987), Kandahar (2001) and Afghan Alphabet (2002)—are best seen as multimedia projects working towards achieving multiple ends, affects and effects. The intention is not to confound the image of the aforementioned reality, but to give it more depth and singularity of appearance. Film, photographs (the premiere of the film at Cannes was accompanied by an exhibition of photographs taken by his daughter Samira Makhmalbaf during the shooting of the film), documents and statistics compiled by the filmmaker and his production house, along with articles on political advocacy and activism—all exist within the same spectrum of sensibility, even if they take away from familiar standards of aesthetic form. His projects therefore roll organically along with everyone around him: friends, family and acquaintances. A minor episode from reality or a small fictional conceit creates the scenario for a work that can facilitate access to the country beyond the everyday images of poverty, deprivation and brutal warfare in Afghanistan during the Taliban regime and the subsequent war with the United States of America and its allies.

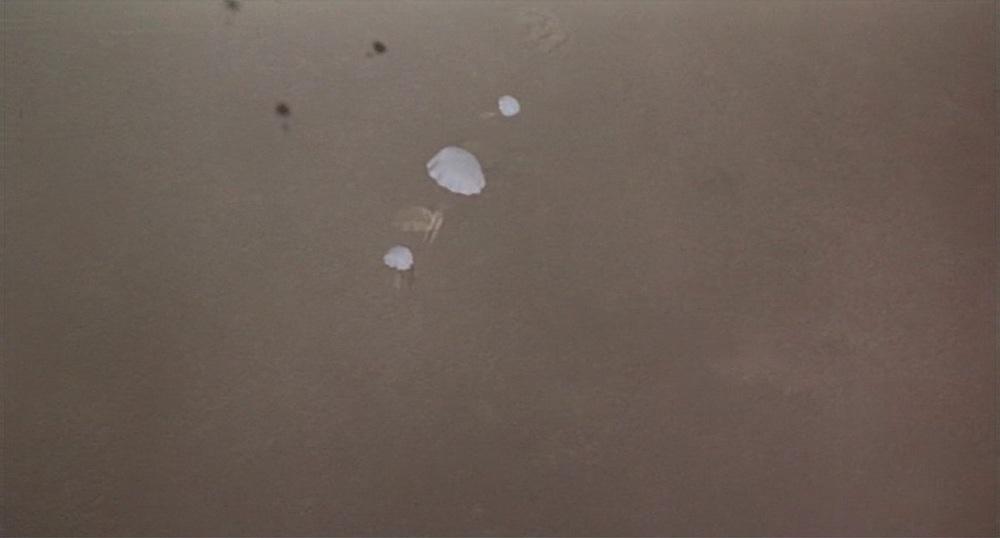

Much like other Iranian films of the period (and earlier), the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction are deliberately blurred—each serving as a repository of questions to interrogate the other, within the same work. In Kandahar, the provocation for the story is Canadian-Afghan Nafas’ attempt to retrieve her sister from Afghanistan. The road-movie structure of the film allows it to show a wide landscape that is fraught with dangers that are both visible and concealed, in the form of landmines that are set off regularly as well as the wide availability of guns and training in violence instead of food or education.

Kandahar also offers a rich ethnographic portrait of the habits and cultural lives of the people of the borderlands. Their social imaginations are truncated by the traumas of war, rendering their bodies equally cut-off at the limbs. It eats away at their personalities which have become importunate, desperate and greedy for a promised new world that never seems to arrive, which makes them increasingly inhumane in the domain of ordinary life.

We meet a range of people from local students to stragglers attempting to bargain for food or limbs, and even an African American Muslim struggling to find God in the bleak landscape. Surrealism becomes the only anchor to communicate the desperate pressure upon the claims of normalcy or reality for the viewer. As Nafas completes her journey towards Kandahar, unlike a typical road-movie there is no great epiphany about the self’s realisation of the world; just an obscure vision of the city rising in the distance, promising nothing.

To read more about Afghanistan, please click here, here, here, here and here.

To read more about Mohsen Makhmalbaf, please click here.

All images from Kandahar by Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Iran, 2001. Images courtesy of Mohsen Makhmalbaf and the Makhmalbaf Film House.