Home in the City: On Sooni Taraporevala’s Intimate Portraiture

Home in the City (Bombay 1977–Mumbai 2017) follows Mumbai through its change of nomenclature, imbued with an affection for its populating faces that reveals the photographer’s position as an insider to its multifaceted history. Sooni Taraporevala (who belongs to—and has documented—the dwindling Parsi community in Mumbai extensively in a separate body of work) captures the city through intimate and quotidian images that reveal her disposition as both “…anthropologist and storyteller” (Pico Iyer in his introduction to the photobook).

The Gateway of India from the Taj Mahal Hotel. (Bombay, 1977.)

One of the most arresting images in the book—which also adorns the cover—is one that Taraporevala took in 1977. It is an open window, from the interiors of her room in the Taj Mahal Hotel that overlooks the Gateway of India. The photographic frame encapsulates within itself a diegetic frame offering a liberating view of the sea, the architectural landmark it upholds and allied narratives of secular solidarities. Thirty-two years later, as Taraporevala explains, terrorists held the hotel hostage through a tumultuous and bloody four days, resulting in a tightening of security and surveillance measures. The “open window” then belongs to this specific moment in the past, when the binary of the public and the private was still a diffused concern.

Security guard at the Juhu airport. (Bombay, 1982.)

Koli fisherwoman. (Bombay, 1977.)

Taraporevala’s subjects include actors caught in unguarded moments on the sets of films she worked in in the capacity of a screenwriter (most famously Salaam Bombay!, 1988), daily figures on the move such as Koli fisherwomen (the original inhabitants of the city when it was still a formative archipelago and who have persisted as agents of nourishment), and the city’s peoples in seemingly ordinary vignettes. A self-organising complexity of a metropolis, Mumbai bespeaks an excess—an inexhaustible pool of impulses, faces and currencies tethered to the contingencies of its inhabiting lives. The subjects demand attention as carriers of narratives, as the frame pulls into focus the individual within the collective against a landscape of mutating urbanity. The photographs, while taken in the same city, evoke a sense of asynchronous contemporaneity—the tug of more than one time and place—the accumulation of bodies suggesting a distinct geological oddity across temporal registers.

Nurse and poster of Indira Gandhi at the Congress Centenary Session. (Bombay, 1985.)

Sarfu and Irrfan Khan at a Salaam Bombay! Workshop. (Bombay, 1987.)

The book issued from an archive of photographs that first came together in the form of an exhibition at the behest of Siddharth Dhanvant Sanghvi (on behalf of Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts) and Devika Daulet-Singh (Founder-Director, PhotoInk Gallery, New Delhi), who had encouraged the photographer to take her work out of her file cabinets. Taken over four decades in moments of intense and casual attention, the photographs were framed in a specific temporal bracket in hindsight, and cumulatively reveal a city that has metamorphosed not only in terms of architectural scale but also in the ways spaces are occupied by its civic lifeblood. In a later photograph, a statue of Queen Victoria has eroded off from its assumed grandeur—a colonial vestige drowned out in the bigger, more intense noise of a bustling metropolis. Indelible yet dislocated from the city’s modern history of rising fundamentalism, the image reveals a flux of histories through a rearview mirror, inscribing Taraporevala’s presence in its syntax as both voyeur and participant.

Raj Kapoor and a fan at the Janbaaz premiere at Metro Cinema. (Bombay, 1986.)

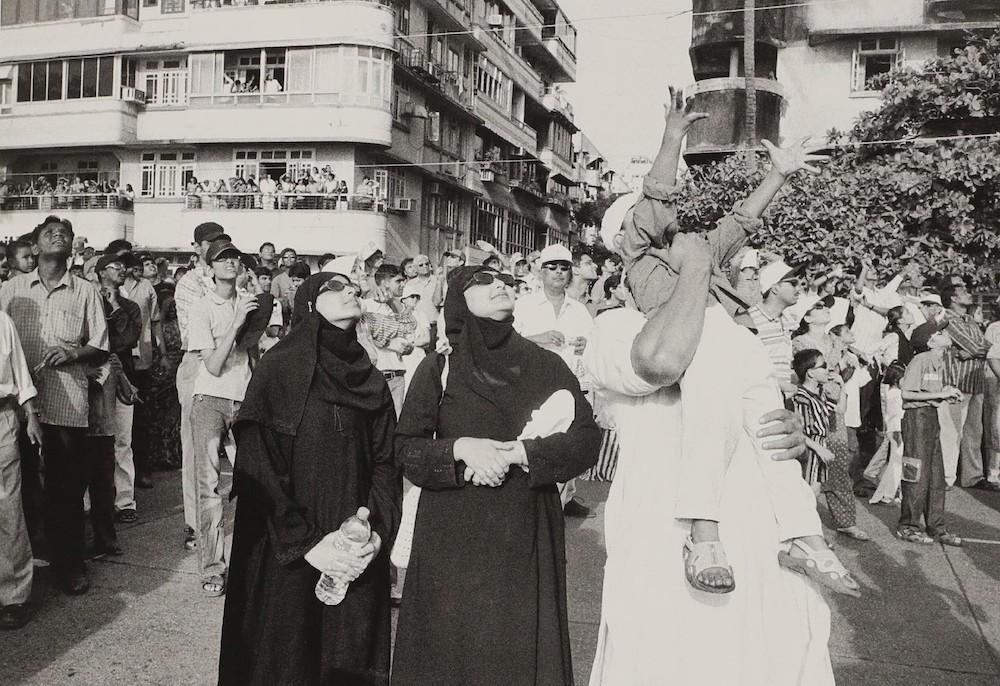

Spectators at airshow, Marine Drive (Mumbai, 2005).

All images from Home in the City (Bombay 1977–Mumbai 2017) by Sooni Taraporevala. HarperCollins, 2017. Images courtesy of the artist and the publisher.