In Guftgu with Absent Bodies: Nida Mehboob on the Persistent Anguish of Pakistani Ahmadis

The Ahmadiyya community in Pakistan exists in scattered geographical pockets as a persecuted minority. The contention between the mainstream Muslim community and the Ahmadis concerns the finality of Prophethood; while Prophet Muhammad is considered to be the last prophet by the former, the Ahmadi sect places its belief in the revivalist preachings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (c. 1835-1908), who proclaimed himself as promised messiah. As a result of this incongruity in theological belief, the Ahmadis were considered heretics—a position further concretised by militant outfits who alleged disrespect to the Prophet and endorsed their boycott. This was achieved through the apparatus of inflammatory oration, rallies and the distribution of flyers and brochures that justified the murder of Ahmadis as a religiously sanctioned act. This has progressively influenced the masses and resulted in the destruction of Ahmadi homes, lives and property. This condition was further exacerbated by their formal criminalisation in 1974, when the government aligned with the position of right-wing hardliners—the second constitutional amendment declared Ahmadis “non-Muslims,” writing them out of the faith. Ahmadis now could not proselytise, pray, greet others in the traditional Islamic parlance, or label their places of worship “mosques.” Their voting rights were also effectively curbed with the introduction of discriminatory mandates, and any “poser” was consequently jailed on the ground of perjury. All of these constraints, cumulatively, have rendered the community vulnerable to sectarian angst—further sanctioned by Pakistani law. Ahmadis mostly live marginal, discretionary lives, hiding their surnames and any material paraphernalia in the house that could betray their identities to neighbours or visitors. This has resulted in the limitation in professional circles of opportunity as well as prospects of marital alliance for women; they are disenfranchised, and any protest or revelation could result in a critical threat to life.

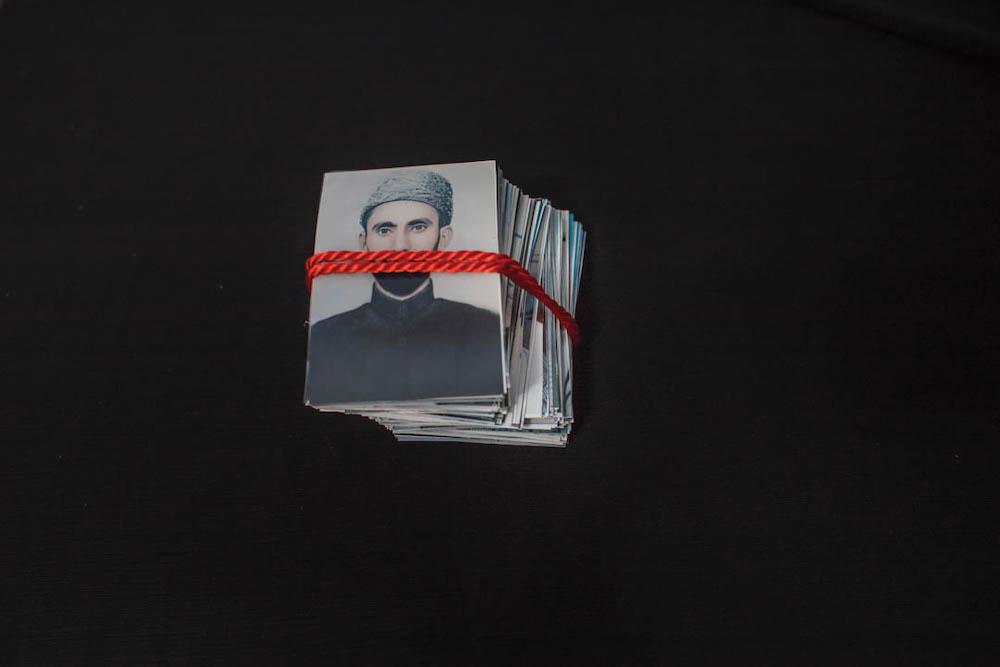

Photographer and filmmaker Nida Mehboob from Lahore foregrounds the plight of this community through a series of staged photographs that reveal multifarious aspects of Ahmadi life through a vocabulary of subtlety. One of the images has a veiled woman facing the camera with shards of broken glass on the ground. On perusal, Mehboob explains, one can discern the headscarf wrapped in distinctive Ahmadiyya style—one that renders them vulnerable to abuse in public spaces upon identification. The grim juxtaposition of a loudspeaker, rose petals (a ubiquitous motif in Muslim shrines) and blood in another image points to the active delegitimisation of the faith through hate speech, which is further bolstered by a pervasive culture of impunity. Mehboob hired actors and volunteers to pose for the photographs, as any model from the Ahmadiyya community could be at potential risk of identity-disclosure and consequent ostracisation. The syntax of her photographic work evokes the perilous imbalance in provisions of security to a part of the Pakistani population that suffers an apartheid-like system premised on claims of blasphemy. This is a community of peoples that undergoes quotidian assault, which thus shapes the ways in which they navigate their histories on paper, as document and as image.

The work forms part of the GUFTGU Zine Box—a compendium of nine zines by nine different artists brought together under the curatorial purview of Offset Projects. A tangible extension of the conversations (or guftgu) conducted by Offset, the collection intends to assemble contemporary sensibilities and responses to the changing social and geographical climates through voices working with the personal, the collective and the mythical. All the authors refute assumed or consolidated identities through their respective bodies of practice, probing instead into political asymmetries of power, fantastical propositions and the links between trauma and text. In tandem, Mehboob inquires into the inequalities she has grown up observing in her immediate environment. The artist mobilises the medium of photography to foreground a diminished community through orchestrated visions that closely speak to their precarity. Her work—published under the experimental pseudonym, “Noon Meem” (Mehboob’s initials in Urdu)—exists in context and reaction to the other voices that populate the series. Each individual zine is physically designed to respond to its content; Mehboob’s is accompanied by scaled reproductions of hate pamphlets and newspaper reports that were mobilised against the Ahmadiyya community in Pakistan. This points to how archival material from the artist’s research process also became an integral part of the final work. The guftgu initiated by Mehboob now enables dissemination of the material within a revised purview, and in deliberate focus away from normative narratives of aggression. Her subjects populate simulated settings that evoke an active reality of state-sanctioned violence, dread and risk, punctuated by real testimonies that affirm a discreet defiance to persevere.

To read more about the GUFTGU Zine Box, please click here.

All images by Nida Mehboob. From GUFTGU Zine Box. New Delhi: Offset Projects, 2020. Images courtesy of the artist and Offset Projects.