Relating to the World: Payal Kapadia’s The Last Mango Before the Monsoon

Payal Kapadia’s experimental narrative short The Last Mango Before the Monsoon (2014) describes a rich, textural experience of the losses entailed in our constant departures from the natural life of the world. With cinematography by Ranabir Das, the film renders a movement that is inescapable and tragic, even as it defines our identity as modern citizens. The nineteen-minute film premiered at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival in 2015, where it won the FIPRESCI prize and the Special Jury Prize.

The Last Mango Before the Monsoon follows the elliptical narratives of two sets of characters. One set consists of a team of cameramen who set up heat-imaging cameras in a forest in order to capture animal movements. The other is an older woman, recalling the past in fragments while consuming a mango. This act seems to signal her reduced, consumable relationship with the natural world in a crowded city.

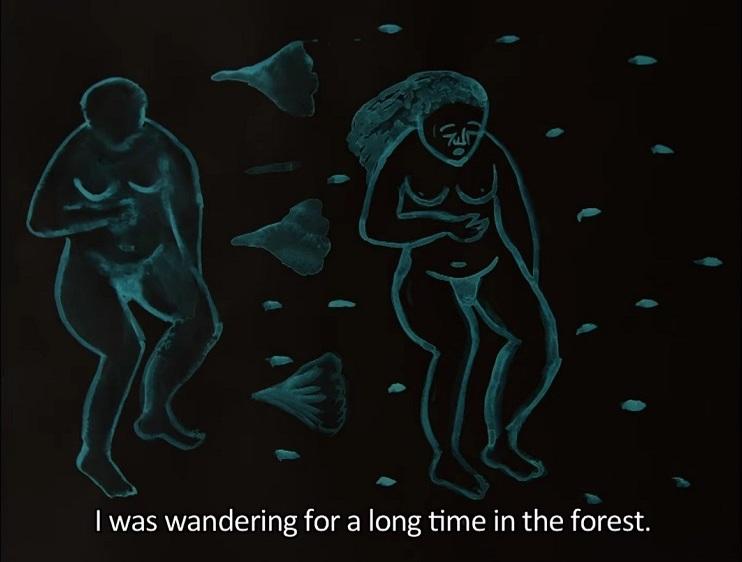

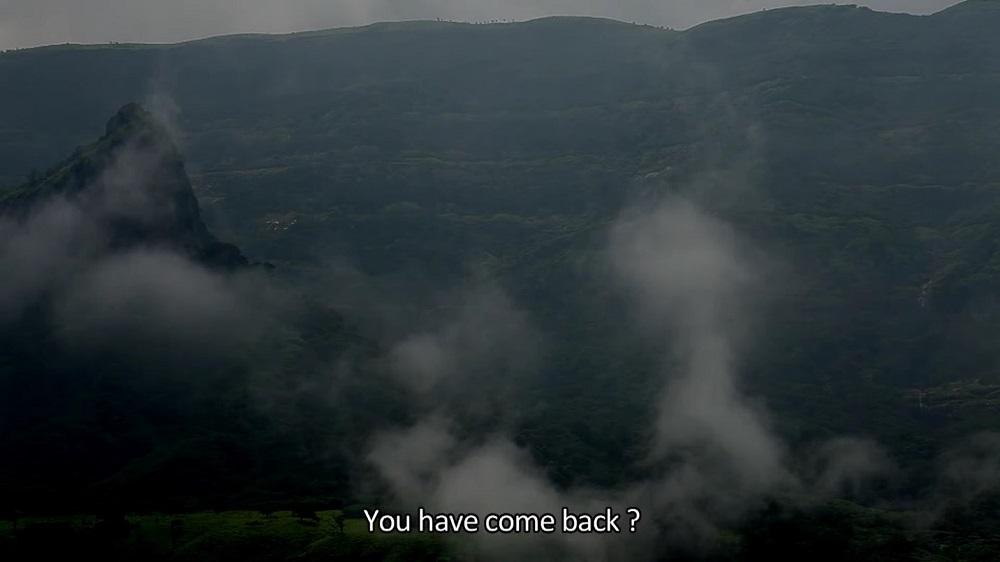

The images are complemented with detailed sound-work and graphic interpolations. Together, these imply a wider canvas of operations than the visible frame, which is frequently shrouded in soft, twilight tones of darkness. It is the kind of darkness that anticipates movement and generation, instead of imposing obscurity and opacity upon the viewer. We see a hint of this in the calm and stately movement of the elephant passing through the fixed frame of the heat-imaging camera, or the soft, masticating sounds made by the unnamed woman as she fixedly eats her mangoes. The film’s distended temporal flow acts as a warm bath, in place of an anxious narrative hook; the audience is offered a chance to ignore the strict elements of plot-formation and consider the radical break between the scenes as its chosen method of storytelling.

Our radical relationality with the organic world is put under stress by the predations of urban life. The sonic and visual landscapes of the latter—borrowing seamlessly from the language of the forest itself—turn around the primal associations that the city inhabitants rely on for marking their own territory with tools like language, memory and built environments. To this ordinary insight about an essential, inseparable human relationality with nature, Kapadia’s film adds a further poetic and evocative argument (and fantasy): that of the need to practise a form of ritual separation (or, viraha) in order to, paradoxically, arrive at a pre-anthropocene eden. This allows for a realisation of a former relationship of intimacy and proximity outside the modern structure of a purely materialistic, extractive relationship that is also suggested by the surveillance cameras’ exploitative relationship between the observer and the subject being observed.

Kapadia suggests the state of viraha with her frequent use of cloud imagery—drifting with elephant-like grace from mountains to the plains. It invokes the poet Kalidasa’s Meghaduta, one of the most poignant lyric poems that explores the quality of viraha as an aesthetic form (rasa). Kapadia’s use of the idea of separation and longing (for a new form), along with her expansion of the filmic canvas beyond its anthropocentric frames of sensory perception, gives it a political edge for our time. Existing at the intersection of the nature documentary, the anthropological essay film and a poetic observation of motion in filmed narratives, the experimental film marks the romantic story of loss as a possible point from where a new narrative of the modern may begin.

All images from The Last Mango Before the Monsoon by Payal Kapadia. Mumbai, 2014. Images courtesy of the artist.