The Death of a Leader: Funeral Processions as Spectacle in the Early Twentieth-Century

Following the death of the Bengali novelist, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay on 8 April 1894, Rabindranath Tagore decided, rather controversially, to speak at the public condolence meeting. In his essay, “Two Poets and Death,” Partha Chatterjee recalled how one of the most prominent poets and an older contemporary of Tagore, Nabinchandra Sen, famously dismissed this: “As a Hindu, I do not understand how one can call a public meeting to express one's grief.” For him, it was sacred and private act—not something meant for public exhibition. Chatterjee shows that Tagore's counter-argument pointed to the emergence of a new “public sphere” in India, one that was still in its youth and, as such, needed to be shaped through controlled cultures of affective expression. Given the development of this public sphere, Sen may not have been able to stomach the scenes that unfolded after the death of “Deshbandhu” Chittaranjan Das, a Swarajist leader and the mayor of erstwhile Calcutta, in the summer of 1925.

Portrait of Chittaranjan Das. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

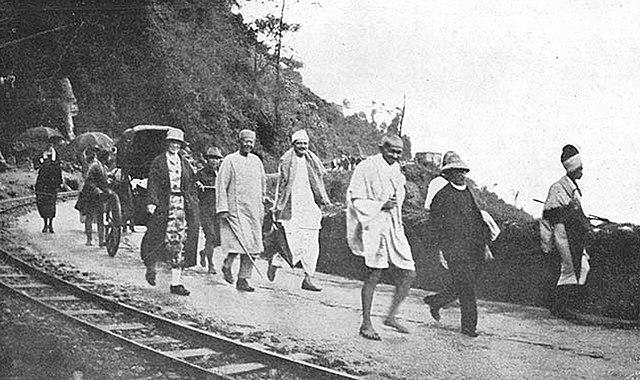

Das had spent the last few weeks of his life in Darjeeling in a house called “Step Aside,” which belonged to a friend. After he breathed his last, on the evening of 16 June 1925, news spread rapidly. According to Prithwish Chandra Ray’s first-person account, his bier was taken from the house to the railway station the following morning, accompanied by a large crowd. It was greeted at the Sealdah Station (erstwhile Calcutta) by a sea of human heads that formed a procession three miles long. Gandhi had anticipated the frenzy and set out a six-point code of conduct that included instructions like “There must be no shouting,” and “No rush towards the carriage.” Only an “authorised band of Kirtankars” would be allowed at the front. The journalist J.L. Garvin reported—rather patronisingly—that, “Calcutta last Thursday was the greatest and strangest scene witnessed anywhere in the British Empire for many a day… No hero-worship in the West compares with the vehement though often fugitive idolatry devoted in India to any conspicuous man who can magnetise the religious or racial sentiment of the people.”

Chittaranjan Das with Mahatma Gandhi and Annie Beasant at the Hill Cart Road near Kakjhora. (Darjeeling, 1925. Image courtesy of Gandhi Heritage Portal. Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

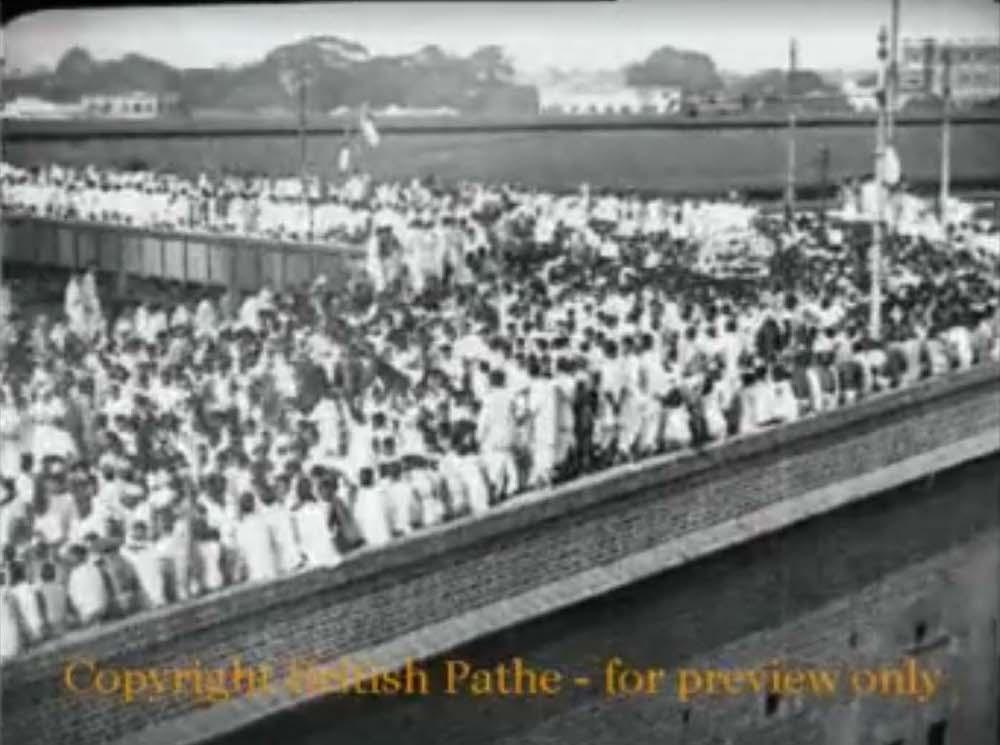

Were Gandhi or Garvin aware that the procession was being filmed by twelve cameramen who shot “…every incident of note, from the Sealdah Station to the Cremation Ground at Keoratala, Kali Ghat”? A thirty-two second clip of the procession is available in the British Pathé’s Reuters Historical Collection, which suggests that the numbers estimated by witnesses were not major exaggerations. The enormous crowds are punctuated only by the occasional platform—from which people are trying to manage the procession—and banners with indecipherable condolence messages. A curious feature is the sight of thousands of hand-fans waving frantically—some regular-sized, some gigantic. Perhaps it was just the June heat. The film opens with the flash of a title card by Gaumont Graphic, which describes Das as “…the first native Mayor of Calcutta and India’s great political leader.”

Still from Funeral Procession of C.R. Das showing a large crowd with a banner on the right. (Calcutta, 1925. Image courtesy of British Pathé.)

Still from Funeral Procession of C.R. Das showing a large crowd, the gigantic hand-fans and the hearse. (Calcutta, 1925. Image courtesy of British Pathé.)

In 1908, Charles Pathé had created the newsreel—as a form that would usually be shown before a feature film. So, it is possible that Das’s funeral was shot with a similar purpose, but the footage also had a spectacular attraction in itself. That same month, an insert appeared in the Statesman, advertising a public screening of the film “…depicting in full detail the Memorable Funeral Procession of the Late Mr. C.R. Das” — “See a whole City in Mourning… a throng the likes of which no city in India has ever seen before.” Among the bonus highlights of the reel was footage of “Mahatma Gandhi and other distinguished men taking part in a public function some time ago.” It was being shown across several major theatres in the city, including the Madan Theatre and the Palace of Varieties, which imported Hollywood films to India, and had a tie-up with Pathé. Although there is a possibility that the reel being shown was a different one, the odds are that either the archived footage in the Pathé archives or a longer version of that were being shown on the big screen.

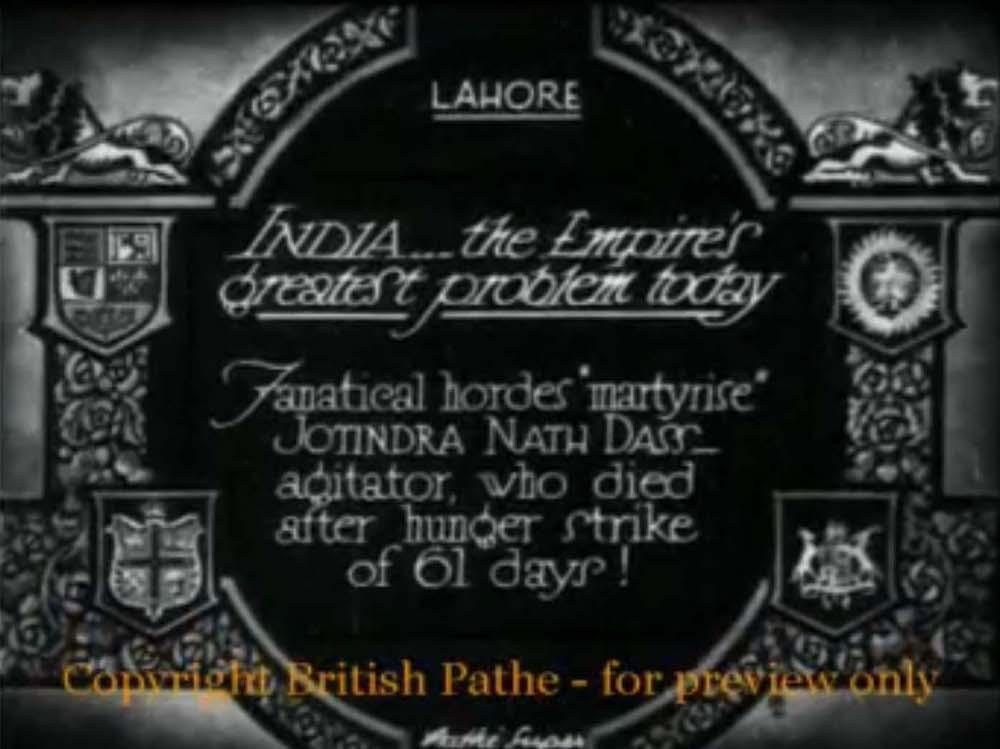

Title card from India: The Empire's Greatest Problem Today. (1929. Image courtesy of British Pathé.)

A few years later, Pathé would also document the funeral procession, in Lahore, of nationalist Jatindra Nath Das (1904–1929). In his case, the more elaborate title card took an overtly political stance: “Fanatical hordes ‘martyrise’ Jotindra Nath Dass—agitator, who died after hunger strike of 61 days!” The film is titled “India—The Empire’s Greatest Problem Today!” And perhaps, the most significant documentation in its archives is of Gandhi’s funeral, which includes images of the burning pyre as well. Funerals had been public events even before the advent of photography or videography, both among the European / Christian population and among wealthy Hindus (particularly Brahmins) in Bengal. The status of the funeral footage as a stand-alone spectacle, however, opens up questions about the relationship between the public, technology and affect. It marks, on the one hand, an extension of the participatory nature of public mourning beyond the physical enactment of the funeral procession through images; and on the other, it projects public grief itself as an object of spectacular interest for those who were absent. Thus, it acts as a curious bridge that connects two divergent public spheres—the mourners on the ground, and the cinema-going public in the early decades of the twentieth-century.

Still showing a crowd on the streets of Lahore from India: The Empire's Greatest Problem Today. (Lahore, 1929. Image courtesy of British Pathé.)