Bridging the Distance: Priya Sen and Nicolás Grandi’s Faasla

Faasla (Distance, 2020) emerges as a result of ten years of friendship and collaboration between Priya Sen, a Delhi-based filmmaker, and Nicolás Grandi, an Argentinian transmedia practitioner. They met in 2011 while teaching at the Srishti School of Design in Bengaluru and their friendship developed as they began working together as part of the Video Poetry Collective. Years later, residing in different countries at the onset of the pandemic, they began a video letter exchange to be featured as part of the Biennial of the Moving Image in Argentina. Originally imagined as a virtual experience consisting of five separate episodes, it is now available to view online as a fifty-minute piece as part of the tenth edition of the Dharamshala International Film Festival.

The resulting film is an evocative, intimate time capsule of sorts. Structured into five parts—each of which can be seen as separate units, but which also come together to build a cohesive narrative—the film captures the months between April 2020 and October 2020. This moment in time was perhaps when the uncertainty of the pandemic—and what its consequences would be—was at its height. Through the film, we see the two moving-image practitioners respond to this event, as well as one another, as they arrive at a vocabulary that can express the bizarreness of the world that they found themselves living in. The film that emerges is a document of ordinary life in extraordinary times, as it attempts to highlight the subtle and fragile intensities of the everyday. The two filmmakers exhibit an instinctiveness in creating their images—reflecting and meditating on what it means to make images in times of crises.

There is a tenderness and gentleness that infuses their work. This is perhaps because the exchange of video letters also allows for the film to exist in the liminal space between the personal and the public. The address is familial and creates a space of trust that is simultaneously freeing. Originally conceptualised for a virtual exhibition, the filmmakers were aware of the way in which the film may be altered in the act of watching, mediated through disparate screens, systems and machines. In a telephonic conversation with me, Sen spoke about the way in which the experience of watching films online has changed in the years following the pandemic—allowing for viewers to stop and take breaks or watch and rewatch a film over forty-eight hours, if they so choose. The epistolary form as fragmentary and episodic thus also lends itself to narrativising this new experience of living in the pandemic—where time is no longer structured in the same way. The film plays with these inconsistencies—with stops and starts and moods that vary—even accepting the impossibility of a resolution in some situations. The banal nature of some of the images often leads the spectator to enter a space of reflection that takes us away from the film, but it also allows us to return to it and become immersed again. There are correspondences, residues and parallels that build a sense of affect over the course of the film as the filmmakers respond to visual, theoretical and sonic cues from each other.

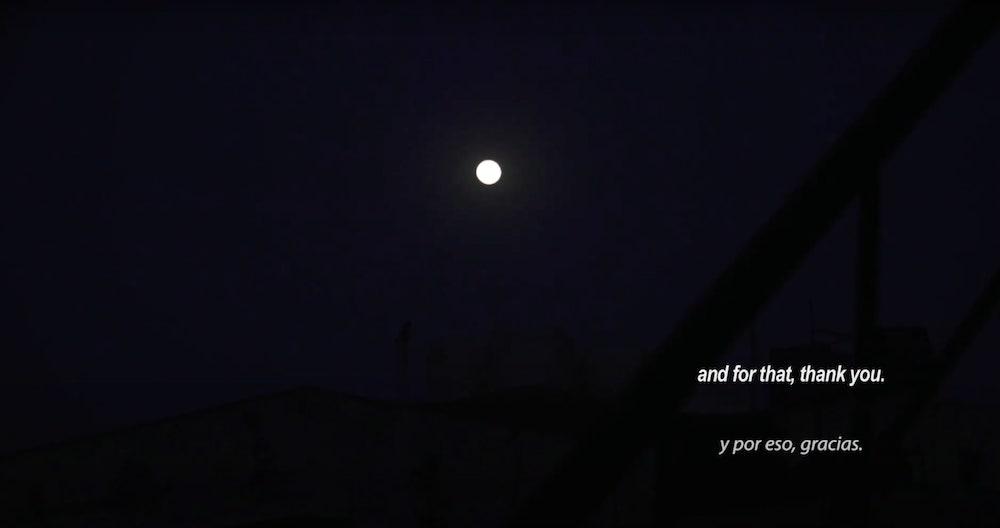

Sen and Grandi have distinct perspectives and come from different contexts, which allows for their personalities to come to the fore. The bilingual text of the film informs our experiences of their interiority. The choice to make the film bilingual is also driven by a political impetus, as Grandi—who often collaborates with other artists (including Lata Mani) from the Global South—is keen to stress the ways in which this opens a space for dialogue and allows for bridges to be built. For instance, the full moon is addressed in multiple ways in the text of the film as “Chandra” and “Mama Moon/Luna” as well as “Jasy ova guasu” which comes from Guaraní. Apart from this political underpinning, Grandi’s engagement seems to be oriented around sensory experiences and the haptic. His initial provocations emerge from exploring the idea of touch (and the lack of it), resulting in images that are textural and often abstract. Sen’s segments are often rooted in the political context of India in the present moment. In one particular sequence, she weaves together footage from the Sunderbans and her travels as she imagines the state of the migrant workers who have been forced to leave the city at the time of the lockdown, only to return to find their homes devasted by the cyclone Amphan.

For Sen, her practice is grounded in a film language that is not interested in looking at the world and translating it as it is, rather it aims to transform the image itself in the act of viewing. She said: “I try to enhance the experience of looking at something—so that it starts to take on a different version of itself when you look at it. This act of transformation allows for meaning to get displaced, and it becomes illuminated from within.” For Grandi, the idea of illumination is driven by the firefly-image, borrowing from Pier Paolo Pasolini and Georges Didi-Huberman. Didi-Huberman writes in Survival of the Fireflies of Pasolini’s encounter with fireflies on a night in 1941 that becomes a metaphor for “…that innocent and powerful joy that appears as an alternative in these times of triumphant fascism… Pasolini even indicates, very specifically, that art and poetry also offer such flashes, at once erotic, joyous and inventive.” Thus, the firefly-image offers light and all its beauty for a fraction of a second in the darkness, before it is extinguished.

This potential of the image to transform and resist appears in Faasla as reassuring. The process of making this film seems therapeutic in the way in which there is an understanding of the context and an acceptance of one another. We see both filmmakers move towards shared memories, poetry, philosophy, music and art for solace—whether offering it to each other or to the viewer—through the course of the film, collapsing distances and distinctions.

The film is screening online till the 14th of November 2021 as part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival.

All images from the film Faasla by Priya Sen and Nicolás Grandi. New Delhi/ Buenos Aires, 2020. Images courtesy of the artists.