Performing the Archive: A Talk by Surajit Sarkar

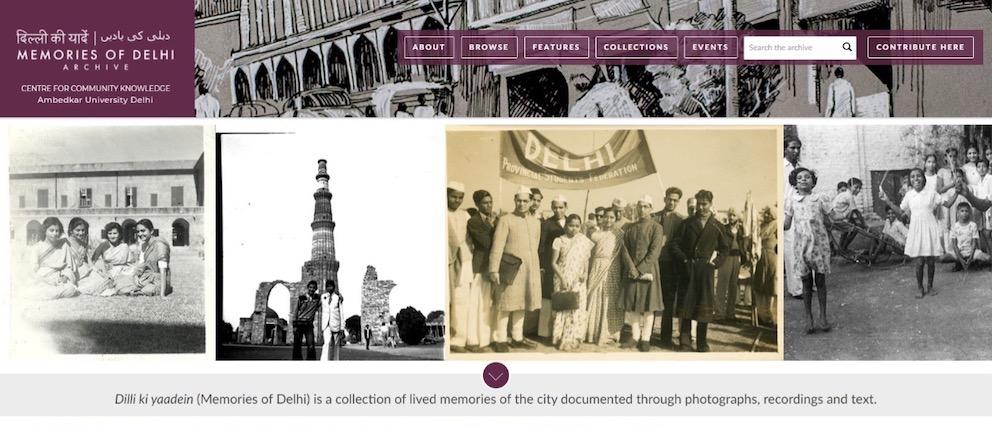

Set up by Ambedkar University’s Centre for Community Knowledge, the website acts as a neighbourhood people’s archive that is also an informal guide to the history of localities in Delhi, filled with personal photographs and documents charting their growth and change over the years.

The Asia Art Archive’s Inter-Archives Conversations series, in collaboration with Nepal Picture Library and Mobile Library: Nepal, hosted a session titled Narrativising the Archive on 7 October 2021, with Surajit Sarkar. Sarkar is an Associate Professor and Coordinator of the Centre for Community Knowledge (CCK) at Ambedkar University, Delhi. Following their fruitful discussions on the multiple sites and meanings generated by archival practices in South Asia, Sarkar’s session “Dialogues with Memory” provided another way of approaching the relationship between public memory and archival practice. Highlighting the work done by his unique department, it was clear that their projects were undertaken with a firm basis in public intervention—by activating archival habits among fragmented communities, promoting dialogue, and creating richer experiences of inhabiting urban and rural spaces in India.

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of Sarkar’s eccentric archive is the method or praxis he hopes to develop with multiple sources, objects and memories, that ask for different codes of analysis and use. Considering the wide disparity between public understandings of (and access to) institutional archives in India, Sarkar’s community-based practice is a useful reminder of how archives can become a means towards achieving social justice and political understanding. Institutional (especially state) archives in India are under increasing threat of being elided with public archives, blurring the state’s control of memory and the public’s employment of it. In other words, do state archives belong to the public, and should public archives be managed or withheld by the state? Are these archives really separate to begin with, or are these categories losing their exclusive meaning?

The Central Vista Project’s proposed demolition of the National Archive of India (NAI) has provoked justifiable outrage among scholars who consider the New Delhi-based archive to be an invaluable repository. The questions of access to this archive have been highlighted on behalf of “accredited scholars” and the public at large, as their petitions also argue. “The public at large” here remains a chimeric entity, however, rarely drawn into this dispute between academic elites and uncooperative state representatives.

Sarkar’s attempt to shift the conversation towards a more active political mode of recovering everyday archives desacralises the hallowed nature of the (“National”) archive. It refuses to prioritise the state’s administrative interest over the public’s reconciliatory practice of dialogue, making access the primary tool of activism. By centring access, the public is drawn more effectively into dialogue, forcing archival curators to think outside their habit of producing meaning from objects that may claim different forms of value. Perhaps this makes the session sound like a theoretical discourse or a quibble over categories, but it was far from that given the stories that animate these neighbourhood archives. These stories have the democratic ingredient of communal participation in them, much like an exquisite corpse—the narrative game invented by surrealists where each participant adds to an ever-extending story of chance and recovery.

Used freely by community members as heuristic tools for engaging with their histories, this practice helps form a more substantial understanding of their past, their present needs and the possibility of resolution, however tentative. Instead of becoming a mythic object of nostalgia, these archival practices are oriented towards a mode of historical recovery that engages the community in acts of remembering, conversing communally and enriching the sense of their own location in the world.

For its “Memories of Delhi” project, therefore, it sought to build up layers of participatory narratives for the fragmentary neighbourhoods that have been carved out of the villages surrounding New Delhi’s central, Lutyens-built enclaves. Even as state histories get written or rewritten, local stories of evolving neighbourhoods tend to elude historians and remain unavailable for the public. Working towards creating access to the memories that create such links of continuity, the “Neighbourhood Museum” programme has seen five iterations between 2013 and 2018. Looking to activate local patterns of knowledge-making or recovering artefacts that aid the memories of neighbourhood-dwellers, the programme helps to create an archive that locals can be taught to use, for their own benefit. It could enhance their engagement with the space of the colony—reviving their memory, for instance, of using different forms of transportation in the past—or it could be about drawing a link between older practices—for example, that of measurement for agricultural labourers and the parallels with changing regulations in the various mandis around the city. Such affective reactions that can weld their connection to the neighbourhood are sought. The meaning of the archive is constantly revised through such practical approaches—flitting between a resource for living, a means of survival and fodder for nostalgia.

Archival practice is not an enclosed space for Sarkar, but an open stage for neighbourhood performances of recovery. The ideal intermixing of forms and media allows digital technology to respond more accurately to demands of access. For the Catapult Arts Caravan, held at Madhya Pradesh’s Hoshangabad District, folk and electronic arts were combined in public performances to articulate common issues and ideas for the locality. Drawing on the melodramatic form of the jatra, stories of the neighbourhood were narrated to an audience of its own: a form of self-revelatory practice through precise activations of memory. Thus, a lot of Sarkar’s work includes making videos and multimedia installations in neighbourhood spaces to create the initial spark for a participatory narrative to begin.

In other projects, Sarkar points to their work as a form of contestation over natural resources like land, water or forests. He spoke about the Ising-i-Waapham (A Question of Water) project at Manipur’s Imphal Valley, aimed at intervening among a host of neighbourhoods that were erupting in conflict over rerouted rainwater flooding and water-sharing arrangements—caused largely by environmental changes, unplanned urbanisation and unregulated flooding. The objective was to create a space where dialogue could be fostered among the conflicted community members. Aided by video works and public performances of storytelling, it created an objective image for their own localities, thereby facilitating rational solutions. Most astonishingly, the programme also recovered an early modern handwritten text (about 400 years old) from Manipur that was lost to modern memory. Containing extensive details about water flows, flood patterns and conservation techniques in the valley, parts of this text were videographed and read out during the public performances to readmit these lost practices into contemporary habits. This led to a moment of municipal education too—as the local administration could take lessons from these older practices of conflict-resolution.

While access remains central to Sarkar’s intervention-led archival practice, the question of what method to consistently apply over accessing such archives remains somewhat opaque. If one was organising such a space, it is meant to be both open-ended and learned at the same time. While conventional archival work still remains a part of his practice, the multimedia form helps to make it accessible to the public in the easiest manner possible. Sarkar’s approach does not claim to solve the problem of such precarious archives that are built and sustained almost entirely by locally-engaged stakeholders, amateur enthusiasts and conscious municipal bodies; but it marks a method by which one may begin such a ground-up enterprise for refitting public memory as an active, playful, and many-voiced agent in constructing state and national histories.

All images from “Dialogues with Memory” by Surajit Sarkar. October 2021. Images courtesy of Sarkar and the Asia Art Archive.