Radio Colomboscope: Connecting the Aural Histories of the South

Colomboscope’s A Thousand Channels radio programme offers a critical smorgasbord of South Asian connections that lie buried under conventional narratives of modernity.

Colomboscope 2022 organised an online radio programme titled A Thousand Channels, for which Syma Tariq curated a selection of audio texts, sound works, music, poetry and conversations. The platform sets up a dense network of connections and conceptual departures with the global south as a critical site on which newer futures may be imagined. One of the ways in which this new channel in contemporary thought could be approached is through the medium of sound. As speakers like Samia Khatun point out in the programme’s first episode, sound bears a complex, perhaps radically disruptive, relationship with modernity. If sight is a central function around which the knowledge-systems of modernity are built, Khatun argues that sound must be treated as a potential bridge towards reclaiming pre-modern systems of being and performing. One is reminded of the arguments frequently made about the nature of poetry changing fundamentally under the impact of colonial printing technology in locations like Bengal—as it became possible for poets to rely on a poem’s visual arrangement in space to create new relationships between the written words, compared to the past when musicality was the only aid to fixing them in popular memory. As if in illustration of this very principle, Khatun invokes a text she found in an obscure Australian mining town, that was titled Qasas ul Anbia (Tales of the Prophets) and included Bengali Sufi lyrics from the early modern period, such as the Yusuf-Zuleikha romance. Sufi romances of such kind are obsolescent not only as literary forms but also as intricately detailed aural worlds that bear only dream-like resemblances even with modern vernaculars. Hearing a reading from this poem is like picking through an old trunkful of words and sounds that have been locked away for several generations.

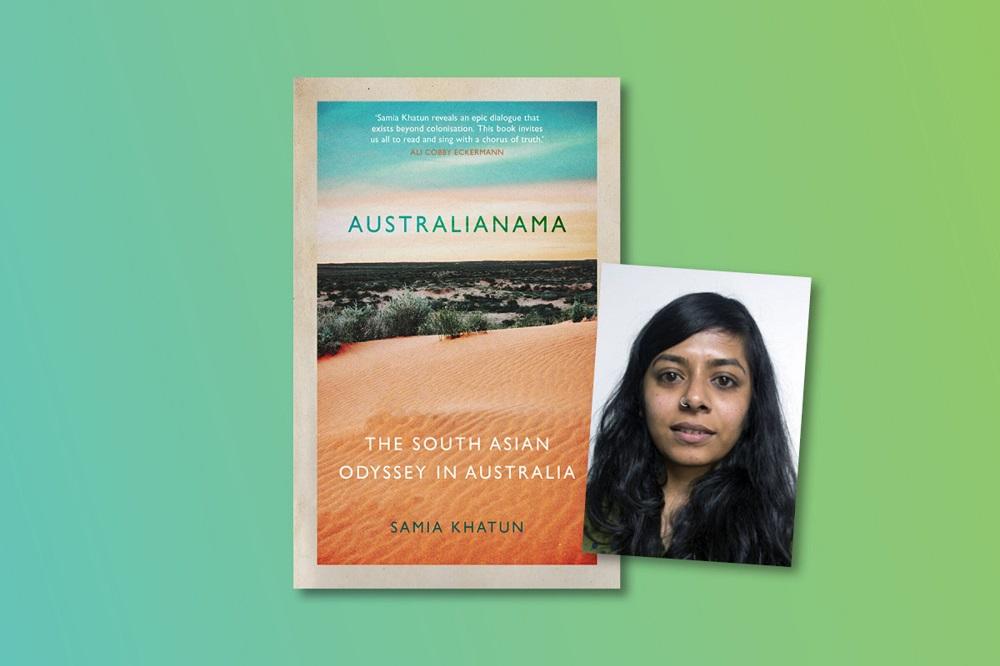

Samia Khatun’s Australianama seeks to disrupt the knowledge structures that co-opt Australia into a purely colonial narrative of progress; instead, she finds common causes between the aboriginal philosophical imaginations and South Asian Muslim practices of dreaming. She introduces Australian landscapes dotted with the ruins of old mosques, that tend to revise our own understanding of the country’s history and landscape.

Tenuous connections of objects, artefacts and sonic structures are linked by Khatun to the more abstract formative influence of dreaming (and its interpretation) as a cultural activity—as endemic to certain Muslim South Asian communities (including her own family) and resonating with the Australian aboriginal concept of dreamtime. As Khatun explains in the wake of her book Australianama, these connections help to reach towards newer models of knowledge with which to understand the subjectivity of South Asian immigrant populations adapting to new lives in countries such as Australia or the United Kingdom. She identifies herself as a dreamer too, meaning it partially to act as a method that allows her to evade the trap of mimicry that colonialism has imposed on its former subjects. Khatun expects it to be a way in which plural visions for a commonly shareable future can be accessed.

Qasas ul Anbiya (Tales of the Prophets). The book narrates qissas (stories) about Koranic prophets, and was reproduced across the (predominantly Sunni) Islamicate world in beautifully illuminated copies.

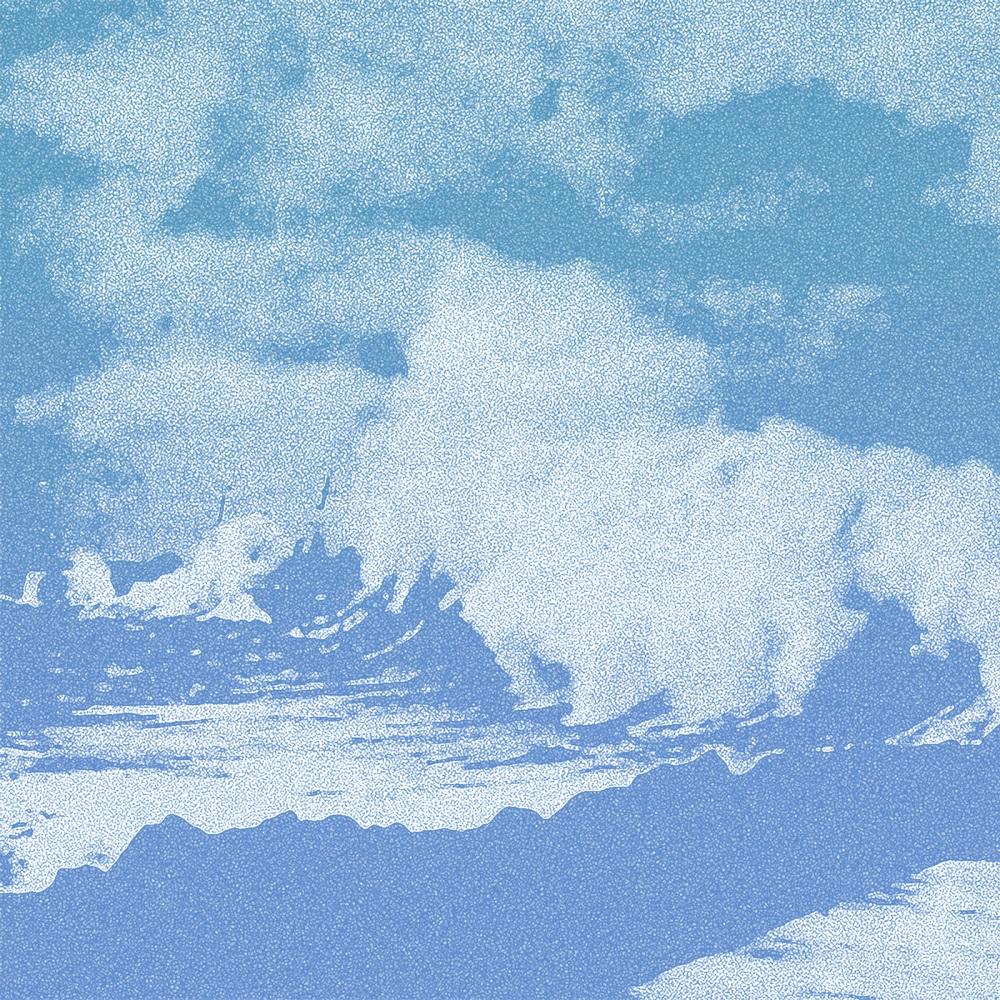

Responding to the acts of racist, anti-immigration policies such as the Australian government’s use of horoscopes to mislead Sri Lankan and Asian immigrants, Lee Ingleton’s sound work “You Will Never Travel” explores new sonic textures that can be enabled by crossing over traditions of listening and sound-making between cultures (such as Sri Lanka and Australia) and technologies. Her use of the audio synthesis platform SuperCollider allows her to create these resonant textures that thrum with resilience and cosmic presence.

Lee Ingleton’s You Will Never Travel.

The remaining segments of the first episode explore the emergent tradition of Miyah poetry from Assam, written primarily by Assamese and immigrant Bangladeshi Muslims. The use of language by the poets reveals the stark nature of their radical practice as they shape familiar contours of Bengali and Assamese into their own politically-charged language of consciousness. The migrancy of language—the festival’s primary thematic proposal—is given a living, breathing body of dissonance and memory, illustrating the force of this every day event.

Khalid Hussain presents another difficult facet of such frequent crossings—the possibility of being stranded out of one’s imaginary homeland. He speaks for the unique experience of Urdu-speaking Muslims in Bangladesh (often labelled as “Biharis”), whose political elites had participated in Pakistan’s project of dominating the Bengali populations of East Pakistan. Since the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, most of this community has been shored up in camps around the country, often stripped of state citizenship and treated as traitors for their betrayal of the Bengali population. Hussain’s call for integrating these communities into Bangladesh’s national life is built on the hope that their language, Urdu, might also survive this assimilation.

Among the blindspots of modern South Asian nationalism are the zones of exclusion created in the national imagination against threatening minorities. Fear of their small numbers drives subcontinental policy-making, such as those that deprive Urdu-speaking, "Bihari" communities of citizenship rights in Bangladesh.

Arfun Ahmed introduced listeners to his radio project Baba Betar, which he had set up in the early days of the Covid-19-induced lockdown in 2020. The radio sought to do cultural work in the form of stories, poems and songs that were sung on air, while it also focused on battling the rash of misinformation that was gripping the world about the new pandemic. Even though Ahmed remained pessimistic about the possibility of free speech in his country, the use of the airwaves revealed a whole new world that could be built up again, critically, from scratch.

Baba Betar was started during the first Covid-19 pandemic-induced lockdown in Dhaka. It sought to dispel misinformation about the pandemic and grew to become a hub of cultural events on air.

The variety of programmes on a single Colomboscope episode come together as a set of alternative readings of spaces that are familiar for their colonial heritage. What enriches the tradition of imperial exchange is the wealth of stories and buried sounds that can be recovered through the work of oral histories and curious objects in alliance with an imagination that can render such familiar histories strange or out of place.

Syma Tariq, curator of A Thousand Channels. (Photograph by Christa-Holka.)

To read more about this year's edition of Colomboscope, please click here, here and here.

All images courtesy of Colomboscope.