As Light as a Husk: Pallavi Paul’s Walking as Alibi: The Dreams of Cynthia

About ten minutes into Pallavi Paul’s online performance Walking as Alibi: The Dreams of Cynthia, a string of voices begin humming tunes that are delicate and haunting as the screen flashes a dictum repeatedly: “Think of a lullaby, Now hum it to yourself.” It is a rare moment in online performances when the skin is pierced by something—in this instance, a sound—that refuses to settle within. As the performance unfolds, excerpts from an earlier work, The Dreams of Cynthia (2016-17), are woven with Paul’s reflections on the communicative failure of language. She considers her preference for the written medium over the spoken, an anxiety about utterance that is a reversal of the very nature that makes Socrates proclaim writing as a “dead” form, as opposed to the liveness of speech in Phaedrus. Socrates felt writing created unpleasant conditions for the supreme authority of the writer, a propensity for forgetting in the reader through the externalisation of knowledge—when memory rests on a page and not in the mind, and the absence of contra or a voice that opposes or tempers discourse. However, Paul is troubled by the notion of authorship as a stable self altogether, the erosion of coherence and addressal in speaking to another as a mode of erasing the other, as well as the speedy discharge that makes voice a phantom medium, quick to evaporate.

And when language ceases to make whole, when it gives in to the “…ravenous hunger of speech”—to what end can it be wielded? Paul turns to narration, translation and bricolage as ways of transforming the material constitution of language. The title of the previous three-channel video work The Dreams of Cynthia is borrowed from a poem by Anish Ahluwalia, translated from Hindi by Paul. In the poem, Ahluwalia conjures the figure of Cynthia, for Paul she becomes a “translated heroine” and a “provocation to analysis.” Cynthia is described in one dialogue by Ahluwalia as “insane,” and within the text of the poem as “mute” and sexually abused. In reading and rereading the poem I have wondered—and I feel Paul shares this query—Is Cynthia a real person? This is immediately followed with—Does it matter? The question is one of remembering—of the elasticity of private memory, its mutability and endurance.

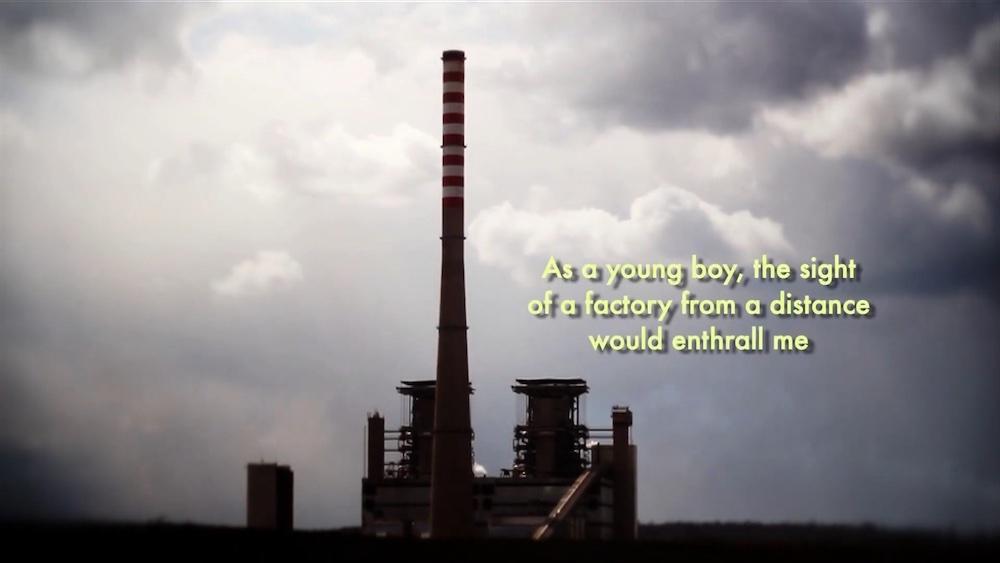

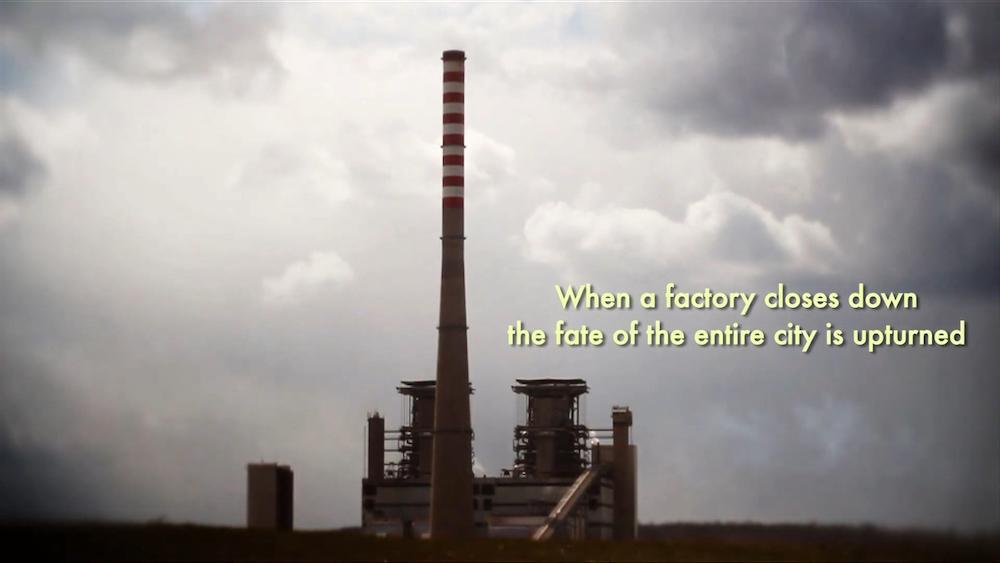

The lullaby refrain in Walking as Alibi is followed by a voiceover of an executioner, which informs us of the closure of a factory. It could be just any waste plant, manufacturing unit or a mill pushing industrial labour back into intergenerational, caste-segregated work. The dignity and perils of waged work can manifest as simultaneous truths in a first-person account of a worker, with the scenes of an abandoned workplace gesturing to a flight of distress. These images are juxtaposed with the fragility of public memory, when clips of news from March 2020 reporting the exodus of urban migrants—who were stranded overnight in the aftermath of the first Covid-19 lockdown in India, and further imperilled by being sprayed with sanitiser—appear as distant events, the bodies on the move framed and presented in a unidimensional way by the reportage. And along comes Cynthia, a trans-artist sporting a yellow salwar kameez. She passes through a crowded, bustling lane, where the velocity of motor vehicles is countered by the pace of her strolling. Trailed by children who are driven possibly by curiosity or the spectacle—drawn as much to the strangeness of Cynthia’s persona as to the camera that walks ahead of her—they match her pace and halt when she pauses. Time is distended by Cynthia’s walk, and when she stops it accelerates again to the rapidity of news dispatches from the field.

The motorway, the street and the highway recur through the video—symbols of modernity that have long been sites of violence: the affective razor of gawking eyes on Cynthia; the anguish of bare feet on gravel treading an impossible walk to the village from the city; the terror of a mob that lynches with impunity; a fascist state’s power to debilitate and maim protesting bodies. Paul is concerned with what can be done when the normative violence of language abets socio-political brutality. In Walking as Alibi, the answer appears to dwell on the possibilities of seeking meaning beyond apparent truths, of “…telling it slant” in the tradition of poetry, introducing tremors to the foundation of the real by using tactics of narrative subterfuge. Paul’s work conjures a cartography where justice and history can walk together, uncertain of the other yet proximate in their influence—much like Cynthia and her young neighbours.

All images from Walking as Alibi: The Dreams of Cynthia by Pallavi Paul. 2022. Images courtesy of the artist and Colomboscope.

To read more about this year’s edition of Colomboscope, please click here, here, here, here and here.