Documenting Dalit Resistance: The Trajectory of Dalit Camera

Dalit Camera was one of the early online platforms in India that contextualised the killings of rationalist activists and scholars such as Narendra Dabholkar, and continues to reflect on the legacy of those murders.

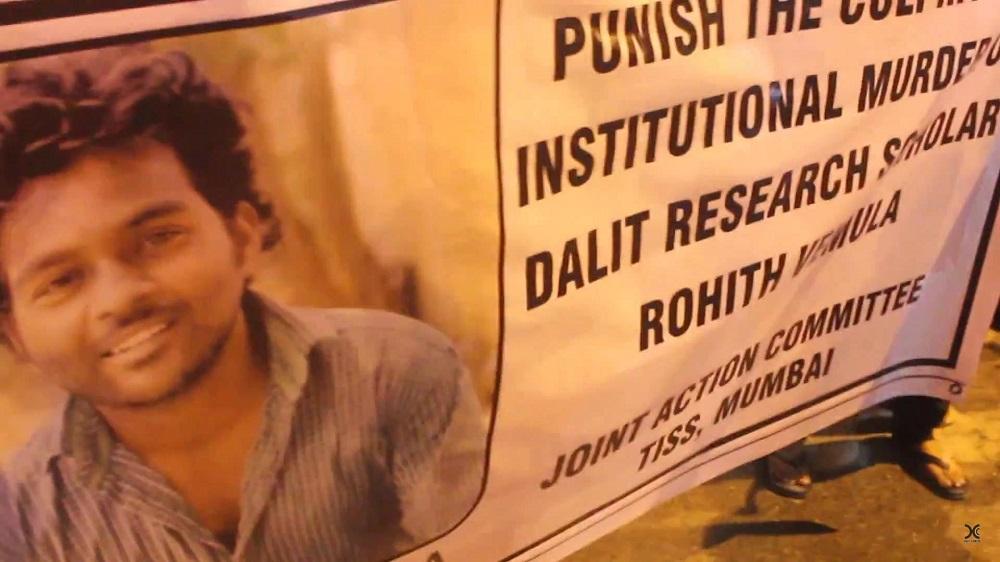

In 2016, the death by suicide of anti-caste activist Rohith Vemula, a student at Hyderabad Central University and an active member of the Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA), prompted a new political wave in India. Videos were made by Dalit Camera (DC), documenting protest meetings, vigils, appeals made by Vemula’s mother Radhika, and popular songs in Telugu celebrating his life. These songs also castigated his tormentors—including the University authorities who had discontinued his scholarship money, and the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student body of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was actively involved in calling Vemula out for “casteist” and “anti-national” activities. These videos worked to mobilise Dalit activists across the country, even as they served to visualise Dalit unity in protest against the atrocity of institutional murder.

Over the last decade, Dalit Camera has become a video-making institution and community media practice that foregrounds the problem of caste as it intersects with various other social barriers in India. Perhaps “institution” is too compact a word, considering that DC has a largely decentralised structure, relying on the volunteered services of undergraduate students and anti-caste activists from across the country. Their YouTube channel works as a first draft of Dalit representation in the media, as they intervene in creating autonomous videos of crucial events in the life-worlds of the various Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi and Other Backward Caste (OBC) communities. DC’s intervention is built on a critical paranoia of mainstream media landscapes that tend to ignore the questions that frame Dalit lives in India. These mainstream platforms, instead, choose to focus on brutal or exotic events that attract the attention of national political players, often with the intention of distancing the community and their interests from normative expectations of equality, justice and the right to live with dignity.

The death of Rohith Vemula provided another catalytic incident for the anti-caste videos of Dalit Camera to become popular documents of a revolution.

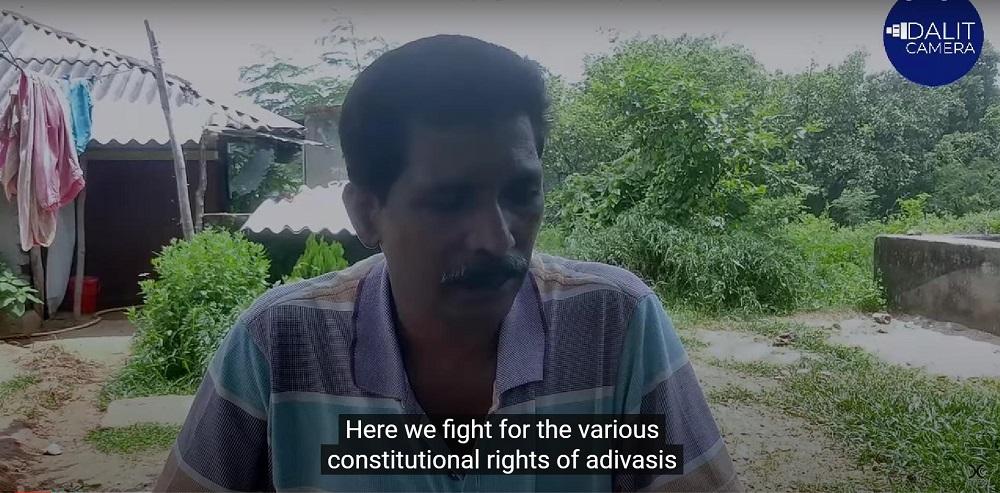

Dalit Camera also interviews Scheduled Tribe activists who are resisting the takeover of their land by both state- and corporate-backed interests.

The inception of Dalit Camera goes back to 2011. It was started by Ravichandran Bathran, a Tamil Dalit student who converted to Islam and took the name Raees Mohammed. His own harassment at the hands of ABVP students at Hyderabad’s English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) and the stabbing of P. Krishnaveni, a Dalit panchayat president in Tamil Nadu, prompted Mohammed to set up DC. He documented the aftermath of the latter tragedy, as protests erupted across the state. The documentary was supplemented by video lectures and critiques by women about the silence that attends the issue of regular violence against Dalit women by both casteist Hindu as well as lower-caste forms of patriarchy. Even at the beginning, then, DC sought to build the idea of Dalit dignity as an object of struggle and solidarity. This would be envisioned through the recovery of community and individual voices instead of assuming a singular identity that spoke on behalf of an imaginary community. In their approach to restoring dignity, DC resembles the radical video art collective Abounaddara, who anonymously chronicled several fragments of the Syrian Revolution, starting around the same time in the last decade. Borrowing from the lyrics of Bob Dylan, they wrote a manifesto titled Dignity has never been photographed, emphasising their awareness of global market forces that attempt to construct the dignity of the other’s image as an exchange-value, or a means to an obscure end. In contrast, their work takes up the “challenge of dignity—even if it can’t be photographed,” looking to represent the other as an end in itself, instead of trying to fit these voices into pre-arranged forms that can evoke compassion or global sympathy. Their questions assume a potency that describes the predicaments of photographing atrocity that was DC’s admitted motivation for starting the collective in the first place: “But how to meet the challenge when the screens that divide and format the world follow a logic of representation that marches in step with the market? How to produce a dignified image faced with the market-produced spectacle of indignity that exhibits the debased corpses of Syrians in the name of an obligation for compassion?”

By centering caste in their discussions of electoral politics, Dalit Camera highlights the ways in which most mainstream political parties in India—working across the ideological spectrum—tend to marginalise Dalit voices.

Aside from Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, DC video-makers have produced the presence of Dalit lives in the public spheres of states such as Maharashtra, Kerala and West Bengal. Most of their videos tend not to be subtitled, making them harder to access for language speakers outside those states and communities. However, their politics of language remains a critical force against regional chauvinism as well. In an interview conducted with Raavi Kumar, the West Bengal State President of the Bhim Army, during the contentious period of state elections in 2021, Kumar spoke about the rejection of false binaries as the object of their political movement in the state. Opposing the Hindi-speaking outsider to the Bengali-speaking insider creates a chimeric, imaginary enemy out of the “non-Bengali” Other, which includes immigrant Dalit or lower-caste families from other states and Hindi-speaking natives who have lived in Bengal for “two hundred years”. It also bypasses the vast population of Dalit Bengalis who are still persecuted for their “outsider-ness” due to their origins in East Bengal- as much by the institutions of mainstream school education and public offices, as organised political resistance by political parties like the CPI(M), during the notorious Marichjhapi massacre in the late 1970s, or the newer depredations unleashed by the BJP government’s promise of creating a National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Dalit Camera hosts speakers and panel discussions that attempt to historicise the recognition of Dalits in politics and the public sphere.

As speakers on the channel, such as Paromita Chakraborty, who works with the non-profit organisation Durbar Mahila Samanway Committee, assert, Bengali academics and researchers are not trained to see caste as a chief operating factor that determines the different material conditions of their lives in the state. DC’s video-work in West Bengal focuses on teaching viewers about the nuances of Dalit assertion and the need for community solidarities across religion and caste, in order to resist the bugbear of Hindutva nationalism. Even as activists like Kumar recognise the Brahminical core of the BJP-movement in India, the offer of their solidarity is conditional on the recognition that Dalit lives—whether belonging to Hindu, Muslim or Christian communities—matter, and that they have always become the first set of corpses in any instance of communal violence. It also depends on recognising the economic depredations visited on the community by stigmatising leatherwork and cow slaughter, jobs performed by both poor Dalits and Muslims in India.

The videos created by Dalit Camera highlight the impact of political discourse on the economic and social lives of Dalit communities. In this video, Motilal Ram speaks about the adverse impact the ban on cow slaughter has had on leatherworkers in West Bengal. Most of the workers belong to either Dalit or Muslim communities.

While the story of DC represents a semi-organised set of resistance tactics to the overwhelmingly sanitised world of Dalit representation in Indian news media, their struggles are far from being recognised in the ways hoped for by founders like Mohammed. There is more pessimism about the technological revolution of the internet that supposedly promises greater egalitarian access to common online resources, than hope for it as a space that can allow the assertion of their presence and bypass mediators in savarna-led news editorial offices in Indian cities.

Even though it produces the complex identity of Dalit resistance over the last decade and more —including frank portraits of internal debates, dissensions and mobilisations— Mohammed forecasts a gloomier picture of the future as online media platforms become equally susceptible to worldly patterns of access, distribution and production, especially in a post-Covid-19 world. Echoing the views of journalist Tejas Harad, who critically rejects the distinction attached to online and offline spaces, arguing instead for a crucial continuity between the two, Mohammed says, “The mainstream media popularises online spaces of only those who maintain the status quo of Indian society. If one discusses Ambedkar leaving Hinduism, no one shares our videos. This is the reason our channel never gets attention. Sadly, until this date, Dalit Camera has not got any mainstream coverage.”

Some videos by Dalit Camera feature academics who speak about the intersections of caste in professional spaces, including sex work, often suggesting ways to think about how their social identities impact their economic prospects.

To read more about the documentation of communities living with marginalised histories, please click here and here.

To read more about a photographic project revolving around the Marichjhapi Massacre, please click here.

All images from Dalit Camera's YouTube channel. Images courtesy of Dalit Camera.