3D Celluloid: Experiments in Indian Cinema of the 1980s

Through the 1980s, the Hindi film industry in Bombay was known to be controlled by the mafia, with the gangster’s moll as the centrepiece in almost every film event. Critics and taste pundits discarded these films as a sorry lot of dirty deadbeats generated for the pleasure of the non-urban philistine. A few industrious filmmakers then took advantage of the surplus money circulating in the industry and introduced the Indian cinema-goer to the concept of three-dimensional (3D) films.

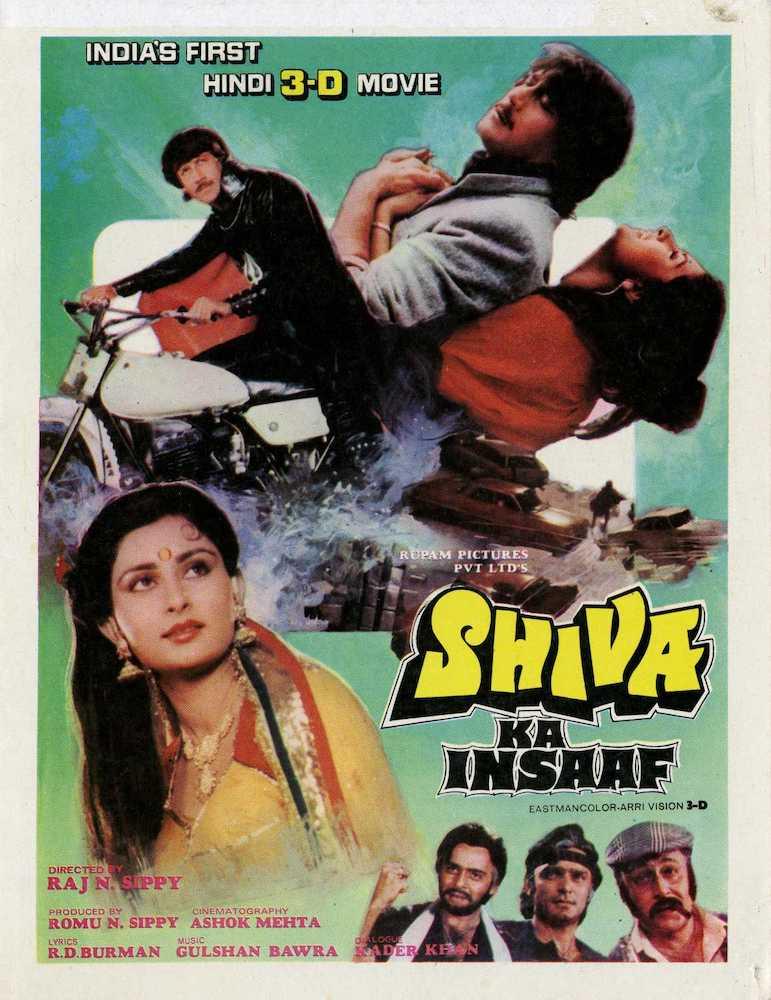

A poster of Shiva ka Insaaf (1985), India’s first Hindi-language 3D film. (Image courtesy of IMDb.)

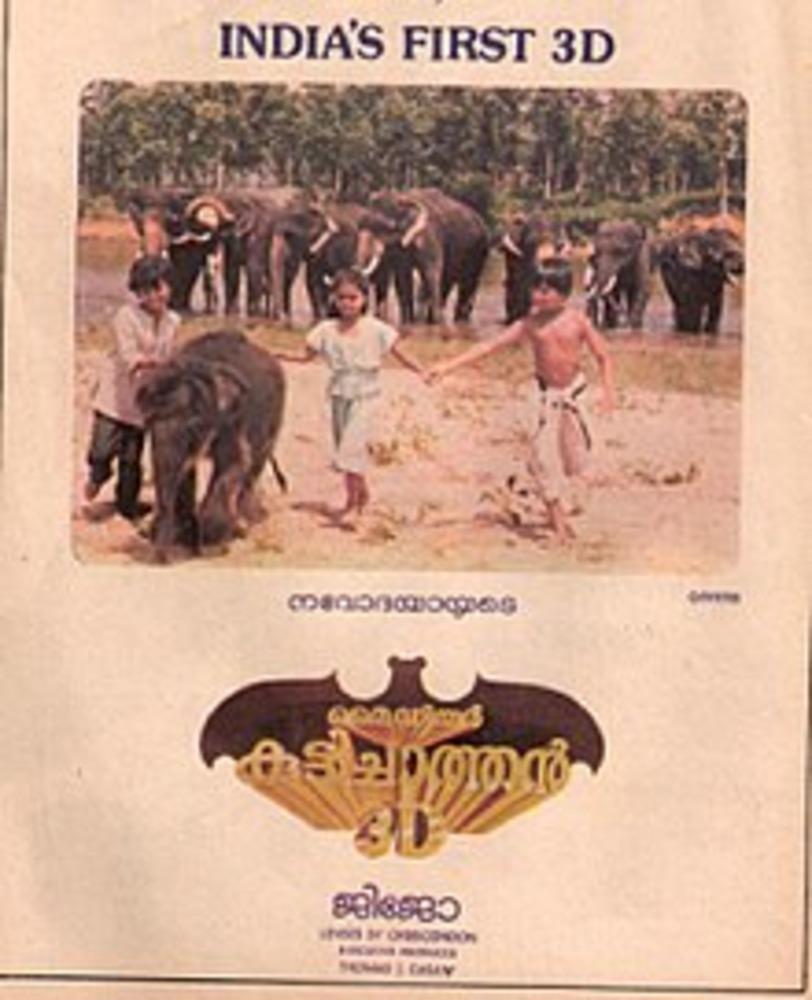

In 1985, Navodaya Appachan—officially known as M.C. Punnoose—produced My Dear Kuttichathan in Malayalam for rupees 35 lakhs. It was the first three-dimensional film to be released in India and one of the biggest money-spinners in the history of Indian cinema. It was later dubbed in Hindi as Chota Chetan (1998). Upon travelling to Los Angeles, Appachan and his son Jijo were mesmerised by the 3D films in Hollywood. They brought back three Arrivision cameras, three technicians, and shot the movie in one year. This was a remarkably long gestation period for an Indian film for the 1980s, particularly when Hyderabad-based Padmalaya Studios would dole out Jeetendra-Sridevi hits on a weekly basis.

A poster of My Dear Kuttichathan (produced by Navodaya Appachan in Malayalam, 1985), India’s first 3D film. It was dubbed into Hindi in 1998 and released as Chhota Chetan. (Image courtesy of Wikipedia.)

Three-dimensional celluloid was not just a novel production technique. The exhibition of the completed films in Indian theatres that were caught off guard with their 2D projectors, primitive screens and busted air-conditioning, contributed significantly to the experience. An article published in an edition of Filmfare from 1985 stated that the major question for critics revolved around theatre owners: would they have enough pairs of spectacles ready before each show, when these theatres, bursting at their seams, often had over 700 viewers? At the cinema halls, Chhota Chetan was preceded by an introductory film on the usage of 3D spectacles demonstrating the sterilisation process and the packing in separate covers. However, a rather carping letter to Filmfare from Bhopal mentioned that having seen Chhota Chetan the writer thereby had abjured 3D films for the rest of his life. “…Seeing the film on a screen which seemed to be made up of distinct rectangles. The projection was just not bright enough…the blame rests squarely on those who take their audience for granted—the producers,” he wrote. A second letter from Bangalore reported that film-goers had complained of eye irritation after wearing 3D glasses, pointing to the questionable quality of sterilisation of the glasses before the shows. Another ingenious problem that irked 3D exhibitors was that the patrons often took the glasses home.

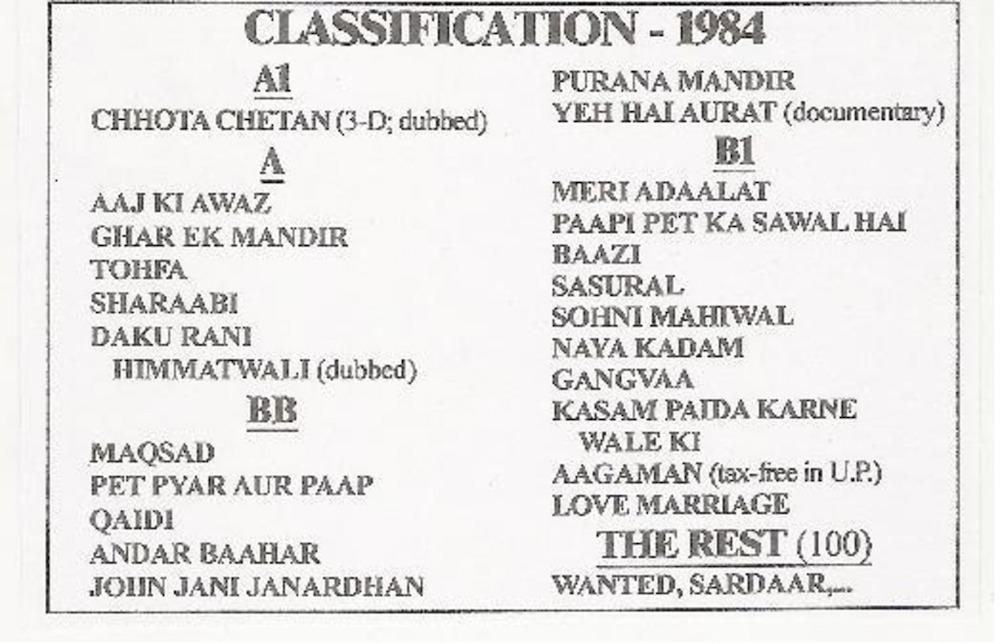

Details showing box-office records from 1984, as published in the journal Film Information. (Image courtesy of forums.itsboxoffice.com)

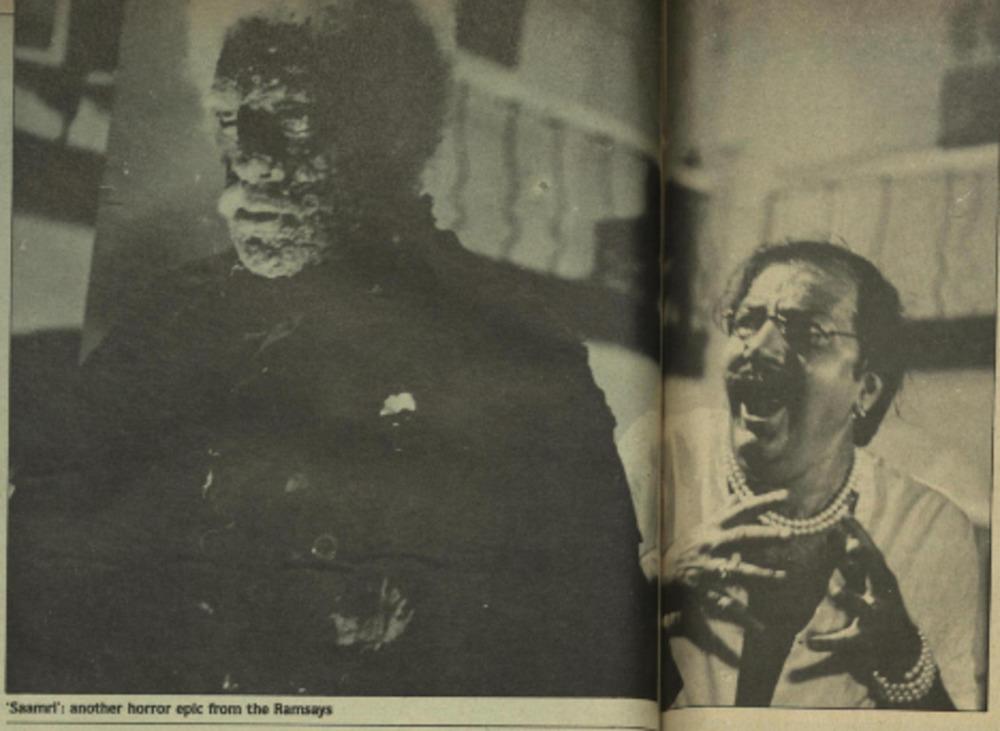

In an interview, the Ramsay Brothers, who had released their gothic monster movie, Saamri—the titular monster from their previous film Purana Mandir (1984)—in 3D, at the end of 1985, say: “The people really enjoyed it, but the difficulty with the Bombay audiences was that they would take the 3D glasses home. We also had to change the lens and put in place a ‘silver screen,’ which made it difficult to exhibit in small centers.”

An image of a still from the monster-horror film Saamri, directed by the Ramsay Brothers. (Image courtesy of Filmfare, August 1-15, 1985. National Film Archive of India, Pune.)

A screen grab featuring an "A" certificate issued by the Central Board of Film Certification for the film Saamri. (Image courtesy of YouTube.)

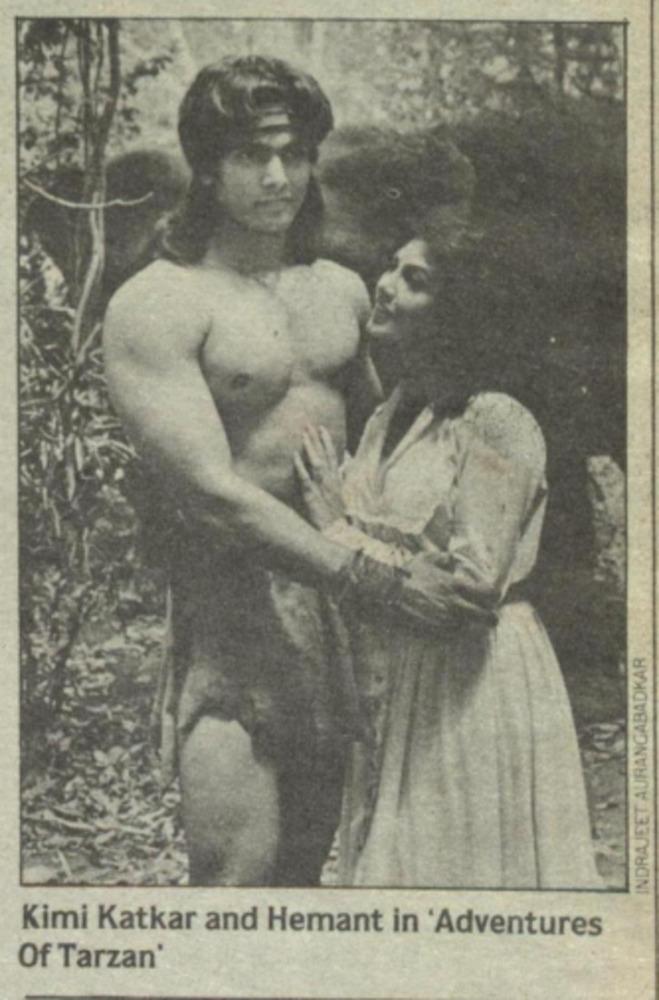

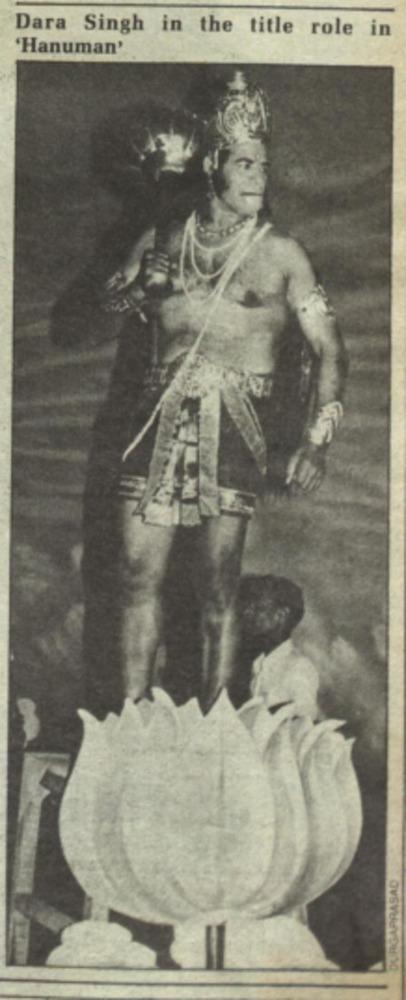

In early film historiography, Tom Gunning has traced the lineage of early cinema to theatre, magic tricks and the circus, and calls it “cinema of attractions” to highlight the fact that narrative played only second fiddle to the thrill of watching images on screen. Gunning concludes his essay by suggesting that the motif of attractions does not expire with the progression of cinema into narrative cohesion but continues to exist in avant garde filmmaking. The industrial decisions around the use of 3D for certain kinds of genres or film cycles in 1980s Bombay resonates with the logic of attractions. In India, film genres that typically relied on special effects like horror, Oriental adventure and mythological, or film cycles such as Tarzan or Hanuman were the first to adopt 3D technology to shock its audiences. Adventures of Tarzan (1985) had later attained cult status in the transcontinental fraternity of B-movie fanatics. Featuring steamy sex scenes between the rather awkward actors—the beefcake Hemant Birje, a wrestler from a mohalla ring as Tarzan, and Kimi Katkar in her debut as the big-breasted nymphet, Jane—it was originally targeted for children. The director, Babbar Subhash, told Filmfare’s Khalid Mohammad in 1985: “I will use 3D for making a pleasant family entertainer which the parents will love as much as their kids…And there’ll be lots of tricks with animals…trained circus animals.” Similarly, at the ostentatious mahurat party of Ramanand Sagar’s 3D film Hanuman (shelved), critics disparaged the lowbrow sensation of seeing Dara Singh, who played the titular character, in “fake jaw and faker tail…the dialogue boomed through the speaker, somehow managed[ing] to combine the 3-D and godly effect.”

A still featuring actors Hemant Birje and Kimi Katkar on the sets of Adventures of Tarzan. (Image courtesy of Filmfare, June 16-30, 1985. National Film Archive of India, Pune.)

Dara Singh played the titular character in Ramanand Sagar’s 3D film Hanuman. (Image courtesy of Filmfare, June 1-15, 1985. National Film Archive of India, Pune.)

The 1980s was a decade derided as an artistic wasteland and a period of recession in studios. The fleeting technology and its attractions emerged and fizzled out quicker than theatres could effectively sanitise their 3D spectacles.

To read about the Bombay film poster as an art form, click here.