Visualising What is Heard: On Nyima D. Bhotia’s Research Practice

Researcher and anthropologist Nyima Dorjee Bhotia’s long-term, personal archival work explores the Walungnga community of the Upper Tamor Valley in Nepal, where he hails from. Looking particularly at how marginal communities situated at frontiers have to negotiate changing dynamics within nation-states as well as the global sphere at large, Bhotia foregrounds the cosmopolitan ideas and devices located in borderlands, where dense exchanges and movements have taken place through trade. His work and propositions highlight how image-making from the region is purposely “made remote” and runs “counter to how we actually live our lives.”

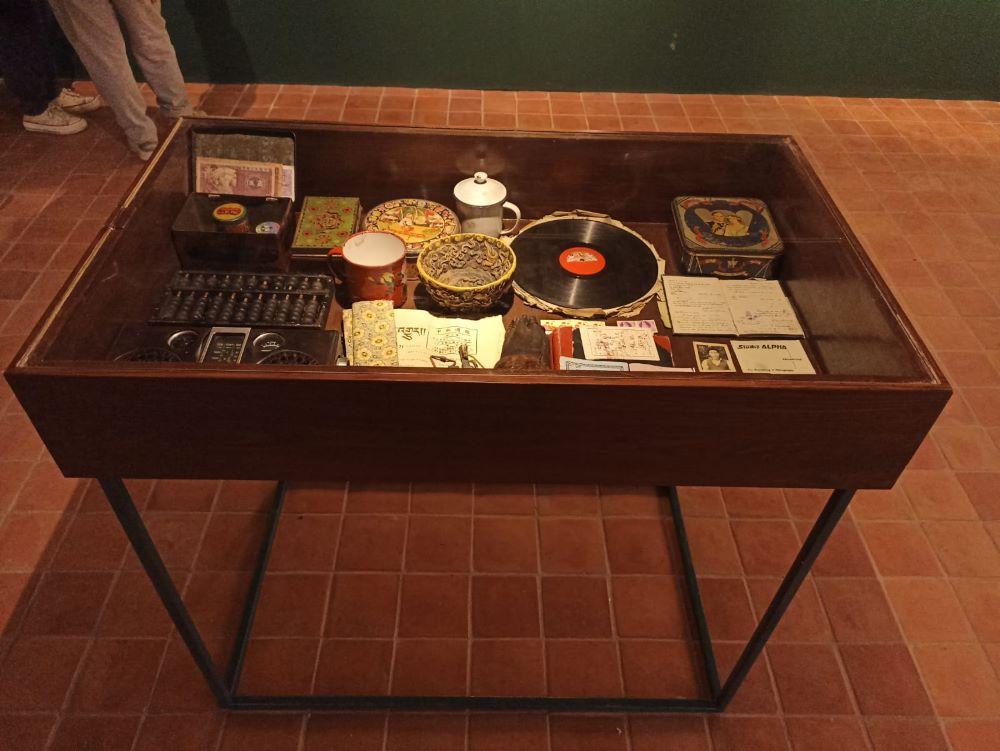

Objects and photographs from Bhotia’s archive were exhibited at Kathmandu Triennale 2077, held from 1 March to 31 March 2022. In conversation with Samira Bose, Bhotia shares some methods and stories from his research and travels.

Samira Bose (SB): The materials and methods of your research include objects, travel documents, mass media technologies and photographs. Your sources for images include family albums from the Walungnga community as well as collections such as the Nepal Peace Corps’ photo archives, with which you establish connections through your own photographs in the present. You have referred to these as “cues to see how people move.” Could you share a little bit about how you work with these?

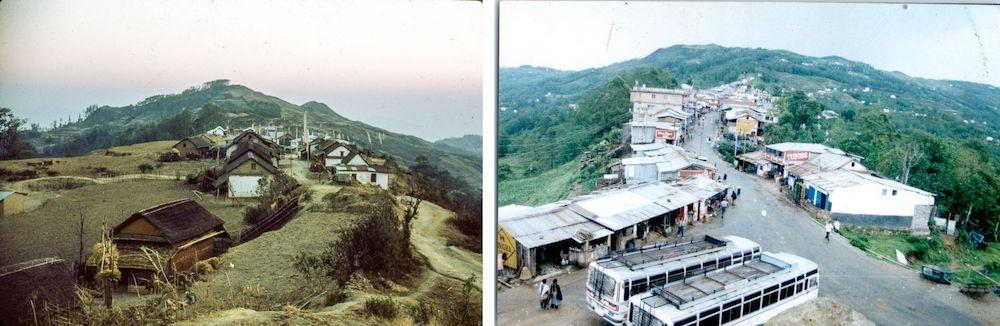

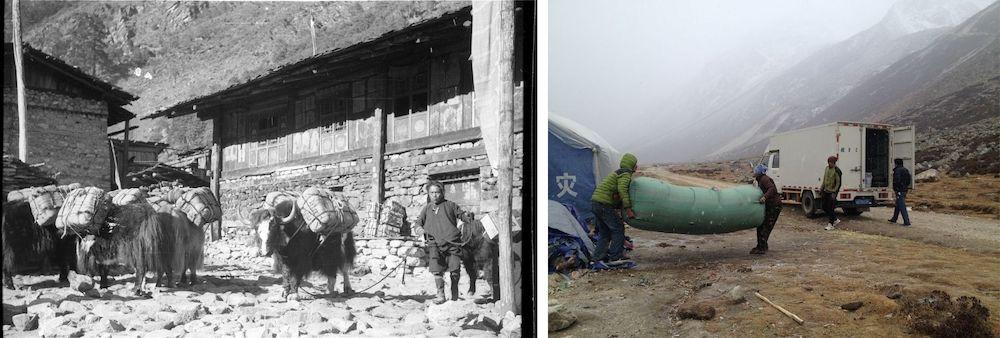

Nyima Bhotia (NB): My research primarily comprises interviews, which I conduct in person. They are centered on the lives and histories of the people in the Walungnga community. I map their childhoods and discuss details up to the present, finding out more about how they’ve moved [across places]. While listening to them, I map migration destinies, where they settled, what their winter migration looks like (a practice in the region where people move to lower altitudes due to frigid temperatures). Given the scarce literature available on the community, these conversations are crucial. The members of the community are the ones who led me to explore the archives of foreign travellers, such as the Nepal Peace Corps, as they remember who took their pictures and in what context. For instance, I was interviewing a monk who was one of the first people to have been born in Hile—a town in eastern Nepal—and whose father built a monastery. He kept referring to “Bob,” so I took hints such as these to research online, and that’s how I found images of the community in archival collections. This cue then led me to several contributors’ photos, including photographer Bob Nichols’ archive, who was traveling to north-east Nepal in the early 1960s and documenting trade or the packs of animals moving through these villages. The 1960s were a crucial period not only because border regimes had changed but also because around then, a flood in my village led to a change in the routes too. I keep sharing the images I access with others or else they wouldn't circulate.

Left: The town of Hile, Dhankuta, photographed by Bob Nichols, 1969-71, Nepal Peace Corps.

Right: A photograph of Hile, Dhankuta from Nyima Dorje Bhotia’s family album.

Left: A photograph by Christopher von Fürer-Haimendorf, 1957.

Right: A photograph by Nyima Dorje Bhotia, 2015.

Though I must say, the Peace Corps have made several errors while captioning these images. For example, they make sweeping statements by referring to the people that inhabited Hile in the 1960s as “Tibetan refugees,” when, in fact, they were Nepalis who migrated from the village of Olangchung Gola. They write patronising things like “they had never interacted with foreigners,” and how small their lives were. In fact, they had had myriad interactions before settling in the village since they were traders who moved between Nepal, Tibet and India. I often intervene on their Instagram posts by correcting them in the comments. They didn’t know much about these people; however, there is no doubt that they really managed to document a key moment in the region’s history. Family archives don’t always go back a long way. The first visual of this region is, in fact, in the sketches and descriptions made by an English botanist named Joseph Dalton Hooker, from 1845. I would like to find visual sources [documented] by the communities in the region, but it might be hard, not only in terms of access to cameras but also that our painting traditions (such as thangka) are not documentary in nature.

I travelled to the region several times with my friend Martin Saxer, a visual anthropologist, and his work also inspired me to consider the role of images in my own research. I took pictures wherever I went, detecting where the community is living today and the smaller details of their lives, thus building on the archive. Admittedly my process is a little bit “western” in the way archives are gathered and constructed, but the visuals are interesting because you can see how communities had settled there, what has changed, what occupations characterise the people—someone’s running a restaurant, someone’s managing wholesale stores. I was looking into community portraits, which depict events and gatherings, rather than individuals. My intention was to look at the community itself and what was important to them. Their family albums were an extremely rich source. It was particularly interesting to see what continues despite considerable shifts, such as the use of prayer flags and [the practice of] worshipping mountains. Additionally, the community is spread across the globe across different places. Social media has made it easy to access and share these images, unlike literature and texts.

Image Courtesy of Walung Kyiduk America.

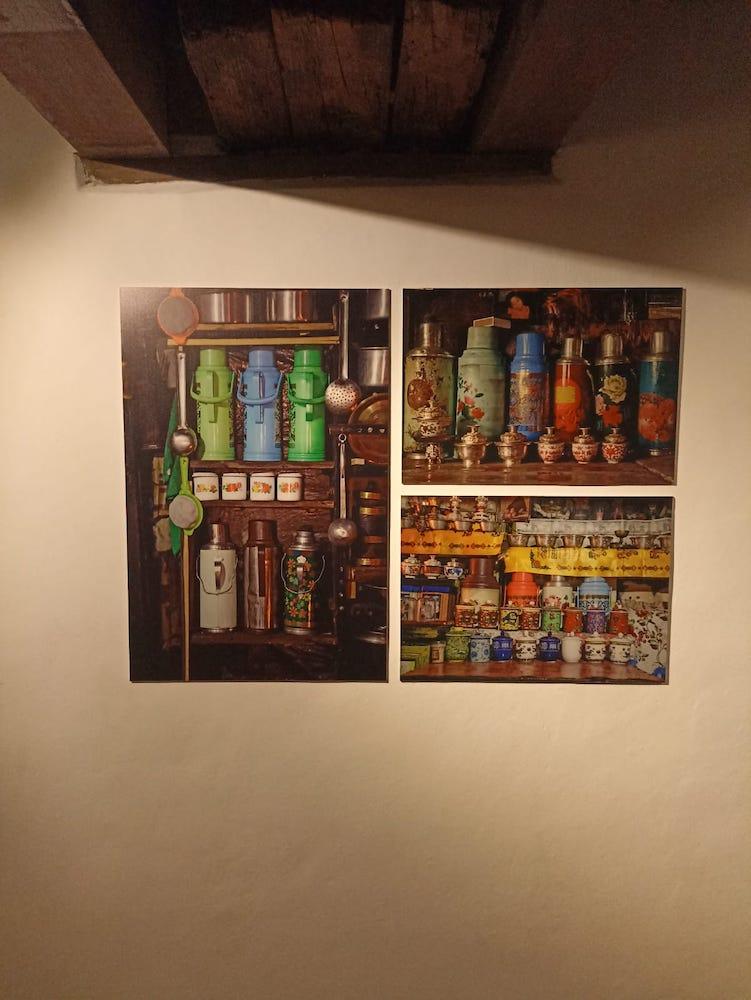

SB: Your practice also involves taking carefully staged photographs of objects—everyday materials such as soda cans and tea mugs—which you claim aid you to visualise the stories you hear. What stories are your images attempting to tell?

SB: Your practice also involves taking carefully staged photographs of objects—everyday materials such as soda cans and tea mugs—which you claim aid you to visualise the stories you hear. What stories are your images attempting to tell?

NB: I have wondered whether my fervent photographing and documenting of objects is perhaps fetishistic. But what I’m trying to do is document and learn from goods that have everyday uses in the villages I visit and research in. I’m trying to document goods that have quotidian use in these areas such as thermos, enamel objects, or common consumer goods that tell a story of today. I'm interested in all the cosmopolitan paraphernalia (the soda cans and the chips packets) alongside more traditional technologies that are built to suit the climate and environment. I make connections between the objects, which I photograph, and their presence in family photographs. I can see how they were used or what has changed in terms of consumption. At a borderland which is a dense node as far as trade is concerned, all kinds of objects pass through. I can illustrate my method with an example: China ceramic cups are like mobile accessories and key aspects of everyday culture for people in the region, often used as gifts in ceremonies, owing to their patterns, or given during marriage functions. I study the material of the cups, have conversations around them and then detect them in photographs. I’m not interested in puritan segregations of the past or the present but in tracing how things change and move.

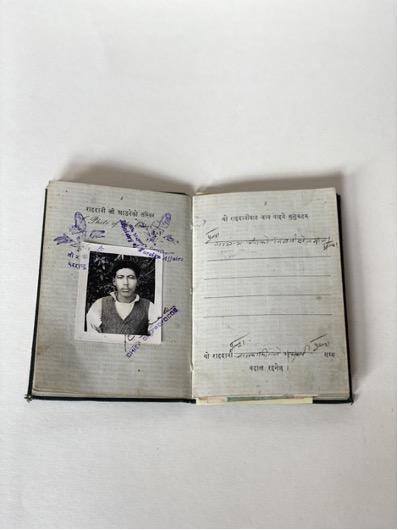

I think my interest in objects and documentation comes from my late father, Nyima Tseten, who was born in Walung (Olangchung Gola) in the 1930s and traded from the mid-1960s onwards between India, Nepal and Tibet. His constant travels lent him a cosmopolitan worldview, and was meticulous in maintaining trading records. While he was not from a trading family, he worked for one as a salaried employee, and, over time, he learnt on the job and began to work independently. One of the last few traders of his kind from the region, he was very entrepreneurial and loved his work. He was still trading until 2006 when he passed away! Some materials from his archive—such as his notebooks and border passes—formed a part of my display at Kathmandu Triennale 2077.

All images courtesy of Nyima Dorjee Bhotia and Kathmandu Triennale 2077.

To read more about artists from Nepal exploring their heritage through their practice, please click here and here.