Analogies of Belonging: An Interview with Jasmine Nilani Joseph

In her intricate practice of observation, Asia Art Future Awardee (International) Jasmine Nilani Joseph draws landscapes of separation that evolve from her personal histories and memories of living in Sri Lanka. Having witnessed the Sri Lankan Civil War while growing up, Joseph’s practice incorporates a reiterative sensitivity in the narratives she sketches, animating her associations with the sites she encounters. As a child, Joseph was displaced from Jaffna to Vavuniya but eventually returned to the former to pursue her art. Navigating the shifting familiarities that unearth themselves in the present day, she manoeuvres the nature of relationships that form over time, the immediacy of residues and her intentionalities as an artist. In conversation with Joseph, Annalisa Mansukhani asks after her recent experiments, her readings of the textures of abandonment and desolation and her studies of the idea of home and its fragmentations.

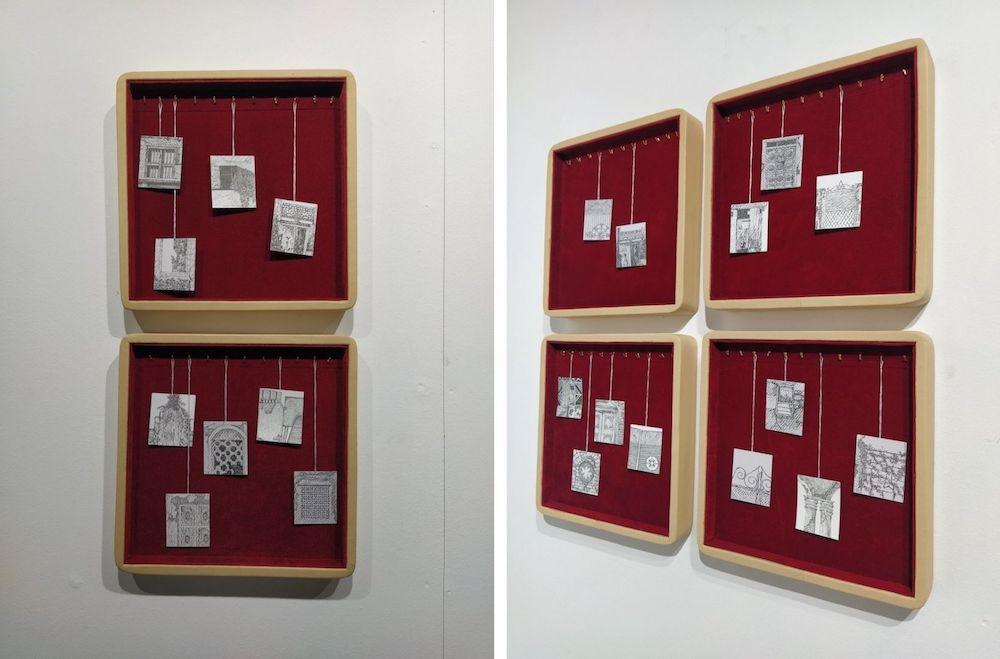

Untitled. (Jasmine Nilani Joseph. Pepper House Residency, Kochi, 2020. Display images of the open studio, 15 works: 8 square frames and 7 wooden boxes covered with velvet cloth, ink drawings on paper. Image courtesy of Kochi Biennale Foundation.)

Annalisa Mansukhani (AM): Your practice accommodates the medium of drawing as a primordial response to what you encounter around you. Are there other mediums you are experimenting with currently?

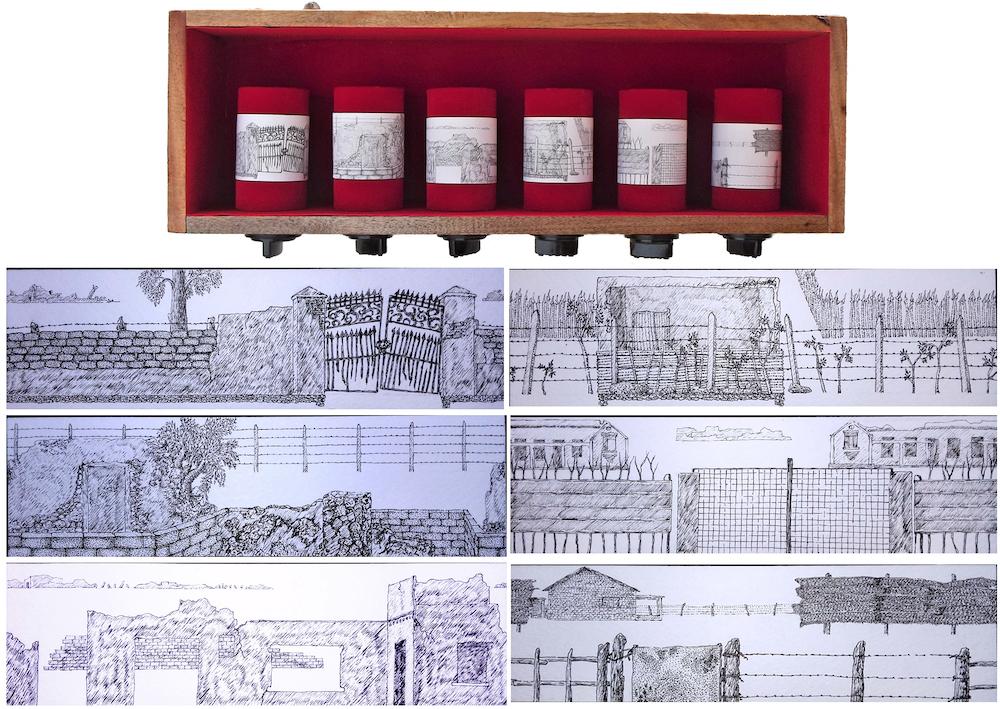

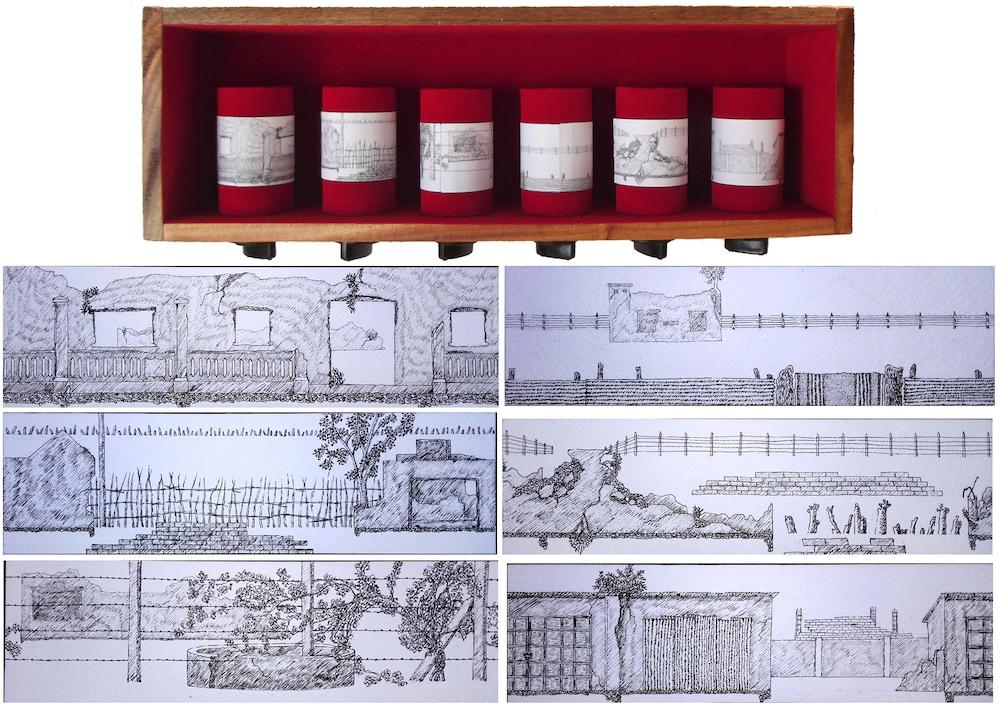

Jasmine Nilani Joseph (JNJ): Most of the works in my practice comprise drawings, created in different compositions by adding various layers. In 2019, I had a solo show at the Art Circle, University of Jaffna where I displayed a series of installations called Yall Jewellery Boxes. These included drawings inside wooden boxes, with velvet cloth, paper rolls and knobs. I wanted to mark a shift in the way I usually display flat drawings, and the structure of the installation encouraged the audience to engage with the work more closely, and I continued to work in a similar manner. As part of the Pepper House Residency in Kochi, I was able to create a large body of work incorporating different methods of display. Upon returning to Sri Lanka in March 2020, the pressure of the pandemic-induced isolation and the many lockdowns urged me to work with new material that could attempt to heal and abate underlying tensions. I used digital technology as a medium to express my thoughts and this became a powerful addition to my practice. With social media, I could display these works on virtual platforms, and was introduced to a larger audience across the globe.

These days I have been busy creating new works that are three-dimensional, in different colours. They aren’t paintings as such but I try to add colours using various papers, textures and backgrounds. I have also used photographs to make video animations. These works break the norms of space, visuality as well as medium, thereby instigating novel interactions with movement, sound and photographs.

Lockdown series #3 and #4. (Jasmine Nilani Joseph. 2020. Stills from video animation.)

AM: The personal emerges as a powerful evocation across your practice. It is something you reiterate in the way you speak of histories, memory and the tensions between home and the self. How do you find yourself weaving the personal into your readings of site? What are the ways in which you seek to activate both?

JNJ: The personal grows alongside the history of the site in my practice. This awareness of site and history is limited not only to me but includes generations of people in the northern province in Sri Lanka, all of whom have grown up with a deep knowledge of what came before us. While our experiences may differ, our personal associations to the ideas of site and context are dependent on our shared histories. If we peel our “self” away from the site, we would be left with an empty body without histories or memory.

When I travel or walk around in Jaffna, the landscape takes me back to my childhood, making me find stories that stem from the place. I currently live on rent in Jaffna; my parents and siblings do not live with me. They live far away but I move through my daily life here with the memories we’ve accumulated over the years. I talk about my ancestors through the landscape and its possibilities. This opens up a way for me to read histories to my viewers, allowing them to imagine and narrate their own histories through my works. As an artist, I think this is my role—to artistically document the histories as well as the contemporary moment that befalls my community, using the personal as a tool. The only thing I am aware of are the limitations that dictate what I say and how I express myself, while also maintaining a realistic perspective of all that I wish to document.

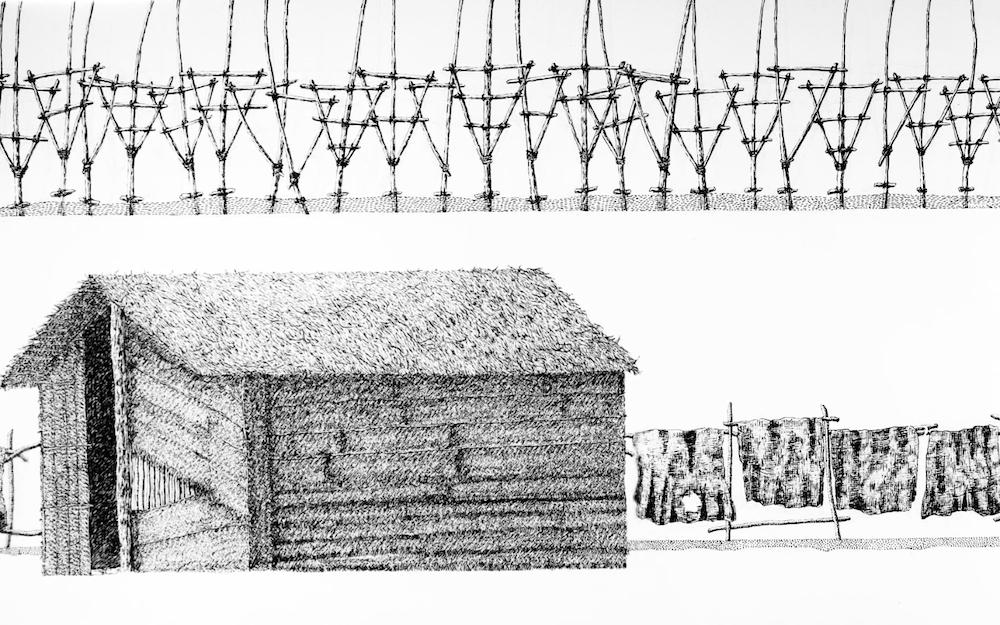

Most of the places and landscapes in my sketches are real places that take shape as line drawings. I insert my perspective, my gaze to depict the growth of the aerial and the vertical in my two-dimensional expressions of the site’s beauty.

Yall Jewellery Boxes, 2019. Combining her signature line drawings with jewellery boxes used by women into an interactive installation, Jasmine Nilani Joseph references the shared memories and histories that define lived experiences in Sri Lanka. These boxes stored inheritances, passed down by women through generations. During the Civil War, many lost their most precious belongings. Replacing the gold with line drawings, Joseph dwells upon the tropes of displacement and destroyed homes.

AM: Your work rests beautifully with the details and immersions that landscapes offer, carefully highlighting textures and their movements. What is the nature of the archive that takes shape in what you wish to document, particularly with regard to communal memory and the geographies of desolation/abandonment in Sri Lanka? How does the idea of home fit in here?

JNJ: I believe communal memory is a collection of personal memories. It is a multiplicity that is of the people and by the people, in turn affecting them both positively and negatively. Communal memory is also an important space in itself, allowing people to belong to sites and their histories. It becomes important to listen to such narratives.

In my drawings, I choose to depict landscapes and architectural sites that relate to my narratives. At times I have had to do away with some spaces to deliver a particular sensibility to my works. Sometimes I add forms from my imagination, emerging from what I encounter. I wish to document the essence of the story, of the relationship that emerges from within the space in an artistic way, differentiating my explorations from the photographs, drone shots and even the maps of the Survey Department in Sri Lanka. This is what grounds my practice.

When we look our history, most of the written texts and photographs are about public buildings and landmarks. There are no stories about people or communities. As a woman artist searching for a permanent house/studio in Jaffna, I was drawn to abandoned spaces and their sense of emptiness. I decided to talk about these houses and document them, questioning the people who owned them in the past. I was then able to draw around 30 houses, spanning Jaffna, and some during my travels to Kochi. Through these drawings, I wanted the audience to think about their home or property which they might have lost in the past. When I exhibited the works in Jaffna, I heard many stories from the viewers about homes lost and found. Here, the idea of home comes through as an understanding, a negotiation permitted by the dynamics of the display and its interactivity.

All images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about how artists have contextualised the Sri Lankan Civil War through their works, please click here and here.