Making New Images: On the Exhibition Making a Photograph by Sunil Janah

An installation view Making a Photograph, a solo exhibition featuring the work of Sunil Janah, at Experimenter Gallery, Ballygunge Place, Kolkata.

Experimenter Gallery’s recently concluded solo exhibition Making a Photograph featuring Sunil Janah’s post-independent industrial photographs carries forward the appropriation of Janah’s diverse contexts of photographic practice into the contemporary frameworks of art objectification in India. It is a movement started in the 1990s, with an exhibition curated by Ram Rahman at Gallery 678 in New York City, when Janah was consciously moulded into the cultural role of an artist. Marking this moment of transition, historian Ranu Roychaudhuri writes, “Although the category of “art” had never been invoked while Janah made the photographs, in this late 1990s moment of revival Janah’s photographs came to be seen as political art objects, possessed of formal autonomy, and using specific situations to address universal messages about human conditions.” The title of the exhibition—borrowed from Ansel Adams’ eponymous book—also places Janah among a global, modernist canon of photographer artists who were conscious makers of their images and, by extension, of the significant artistic forms they generated.

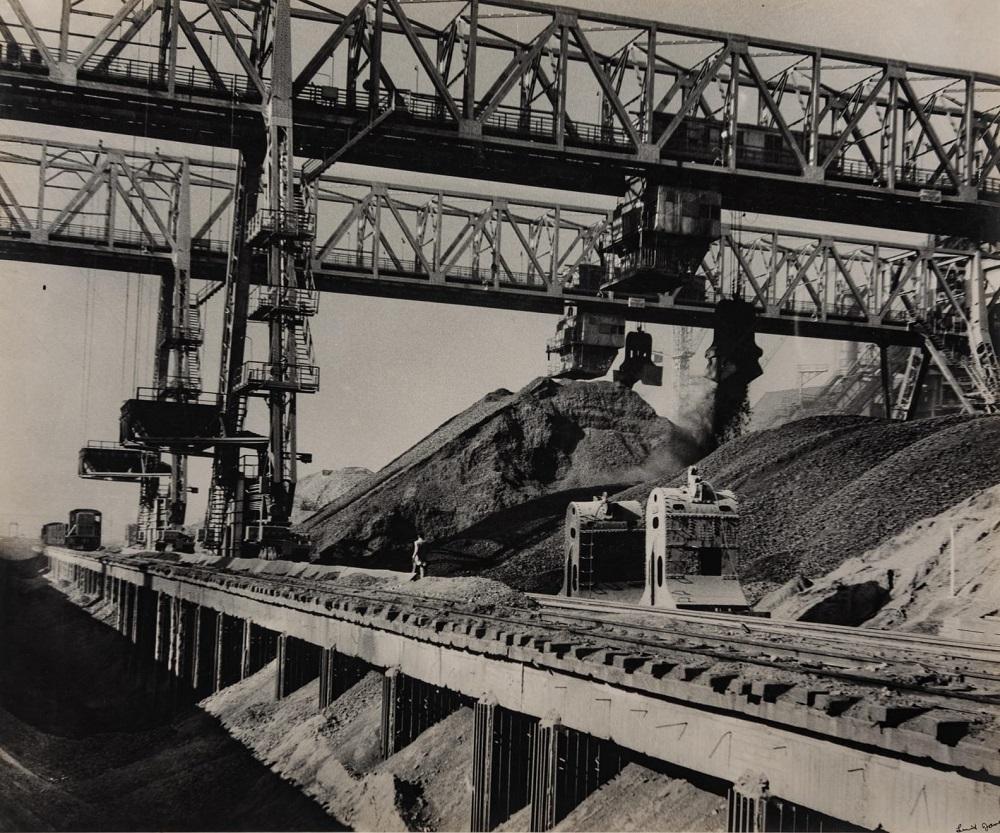

Bhilai Steel Plant. (Sunil Janah. Early 1960s.)

This movement explains the placing of the photographs in a gallery space, largely stripped of their original contexts in newspapers or weeklies like The Illustrated Weekly of India. This does not, however, necessarily impoverish the work of Janah. In fact, it opens up a space for ambiguity and ambivalence, delineating a curiosity-driven search for formal innovations by Janah that has previously escaped more doctrinaire readings of his images. Nor does the absence of a thickly textured recreation of the “original” contexts of appearance for the images signal a clear rejection of the political imagination of Janah. This imagination was undergoing transformation and transition at the time as well, after the independence of India in 1947 and his expulsion from the Communist Party of India in 1949. As the events of the early Nehruvian years of industrial growth recede from our memories, Janah’s photographs still bear powerful traces of witnessing the human labour that went into shaping the physical landscape of industrial India.

An installation view of the exhibition.

The suggestively autonomous placement of the photographs allows us to see clearly into the methods by which Janah rendered such “secular icons” as significant, monumental projects of their time. Factories and iron and steel plants appear to be hewn out of the country’s landscape and its smaller hillsides, resembling the rock-cut and humanly manipulated spaces of the Ajanta and the Ellora Caves. Drawing a pre-modern spatial imagination into these photographs allowed Janah to infuse them with mystery and wonder, rather than with dumbstruck awe or singular, ideological critique. In our retrospective gaze, the “majestic structures” he photographed also reveal contrarian narratives of industrial modernity concealed within the plain view of the photographs themselves. What were symbols of utopic futures to come, to our contemporary eyes, they now reveal an early index of modernity’s tendency towards obsolescence as a temporal condition of innovation. The factories also appear to our eyes today as sites of excess: of wastage and spillage, leading to various forms of environmental hazard. This is indicated by the billowing, thick plumes of smoke wrapping the natural landscapes in a foreboding chokehold. Janah’s photographs still manage to pick gaps between these imposing structures and their human builders. They point out the essential presence of men and women labourers who interacted with these machines regularly to produce their own modes of rest and engagement.

Coils of Wire. Unique Silver Gelatin Print. Early 1950s.

New modernist contexts for Janah also help us appreciate the striking resonance of images like Coils of Wire, photographed in the early 1950s, showing a close-up of a stack of coiled, steel wires. It helps secure the autonomous power of the photographs in the exhibition by focusing our attention on the abstract processes at work within the frame, such as the repetition of patterns and its movement towards non-referentiality. The industrial material of steel imbues it with the power of innovation, of manufacturing or “making”—as the title of the exhibition reminds us—as a powerful impulse that lies within the viewer of these images as well. Its resemblance to a stack of toy slinkies marks it even more as an invitation to play with industrial material. It perhaps signals an optimism (including a political optimism) that Janah would have felt at the time, even if he thought poorly about these images later on. These shifts suggesting a map of sensations in his images— rather than pure intellection—reflect something crucial about Janah’s practice during those early years after independence. They reveal the tactile world of freedom, of new possibilities, emerging out of older ideological scars and struggles and the power of the photographic image to reveal the ambivalent promise of the future.

Construction at Calcutta Port (Kidderpore Docks, Calcutta.) (Sunil Janah. 1947.)

All images courtesy of the Experimenter Gallery and the artist.

To read more about the work of Sunil Janah, please click here and here.