Bani Singh’s Taangh: Triumph, Loss and Longing on a Hockey Pitch

The Summer Olympic Games were set to resume in 1948 in London after two consecutive cancellations in 1940 and 1944 on account of the Second World War. The juggernaut of the Indian men's field hockey team would continue its march to win its fourth successive gold. They beat Austria 8-0, Argentina 9-1, Spain 2-0, and the Netherlands 2-1, to meet England in the final at Wembley Stadium on 12 August. The scoreboard read 4-0 at the final whistle. On the face of it, a story of triumph, not entirely unexpected. But while Bani Singh was making Taangh/Longing—trying to piece it together from the memories of her father, Grahnandan Singh (or Nandy Singh), and his old teammates—she realised there was much more to it than what met the eye.

The Indian Olympic hockey team, 1948.

Grahnandan Singh (1926-2014) was born in Lyallpur (present-day Faisalabad in Pakistan). His love affair with hockey began during his student days on the iconic Oval Ground of the Government College in Lahore. He was one of five “Ravians” who would represent their nations in hockey at the 1948 Olympics. Following the Partition of British India, Singh found himself in Calcutta with a job at the Port Trust, where he was reunited with his old friend and team-mate, Keshav Dutt (1925-2021). The two shared an apartment, as Dutt recalls in an interview, “eating daal-roti and occasionally vegetables.” The piggy bank that collected small change would be sacrificed on special occasions for a bottle of beer, split two-ways. They continued to represent India in hockey; only now, instead of Lahore, they played for Bengal at the national level.

At the time Bani Singh started recording the interviews, her father had lost the ability to speak, having suffered a stroke a few years earlier. Yet, he communicated either by scribbling a few key words with an unsteady hand, or by answering “yes” or “no” to questions posed by her interviewers, often in the form of old photographs. (Thus, along with their use as archival footage in the film, photographs also serve as memory prompts for the Olympian, often opening alleyways into the past he may have forgotten.) Of course, Bani Singh’s own sedimented memories of her parents are a lifetime in the making. She recalls, for instance, how Grahnandan Singh had once asked her mother to “put on her best saree and took her off to the stadium where he had won many of his trophies. It was his way,” she observes, “of bringing together the two loves of his life.”

Grahnandan Singh writing on a whiteboard assisted by Bani Singh.

Keshav Dutt and Balbir Singh fill in the gaps in the narrative of India’s triumph at the 1948 Olympics, with Gurbux Singh making a cameo appearance to offer a panoramic view of Indian hockey. The Indian and Pakistani players had been warned by their respective managements to maintain distance from each other in London—their camaraderie apparently too much of a threat to the fragility of the emerging national identities. “Both sides, Pakistan and India, were very clear in their minds that they are going to meet in the finals,” says Dutt. “They never in their wildest dream thought that Pakistan is going to lose to England [in the semi-finals].”

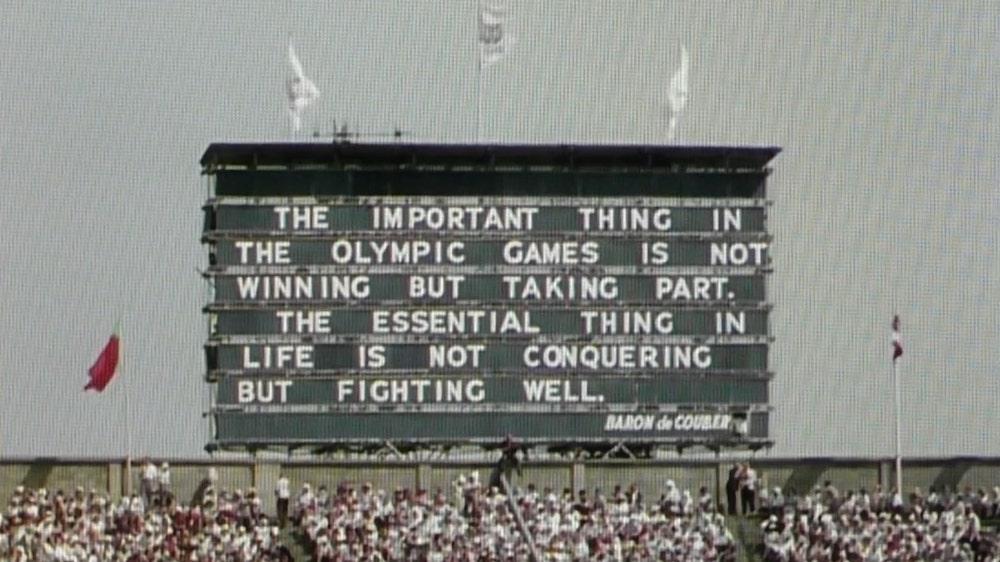

Pierre de Coubertin’s message on a scoreboard at the London Olympics.

While the former president of the International Olympic Committee Pierre de Coubertin’s famous words, “The important thing in the Olympic games is not winning but taking part,” were displayed on the scoreboard, the conditions that were engineered to favour the European style told a less savoury story. The pitch was wet with longer, untrimmed grass. “It was not hockey being played, more like rugby. I mean, Indians and Pakistanis were artists,” says Dutt. Pakistan lost to England, unable to adapt. “But Babu [K.D. Singh] was a genius.” There is a glint in Dutt’s eyes. On his advice, the Indian team changed its style, keeping the ball in the air as much as possible. They won emphatically and the Indian flag was raised to celebrate the victory of the newly independent nation. “It is not a moment to be explained, but to be experienced,” says Balbir Singh.

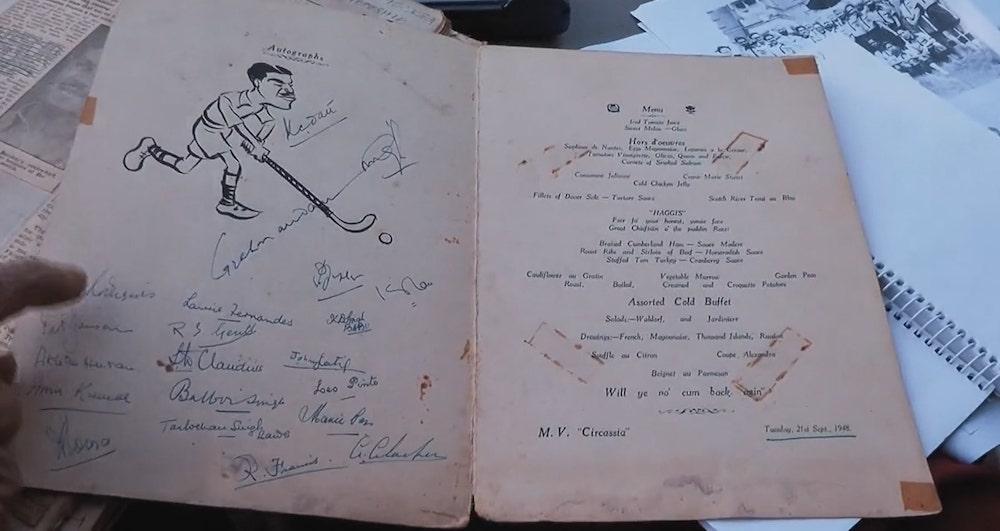

Caricatures of the team drawn by The Times of India cartoonist, Ahmed, and signed by the players.

The viewer may be forgiven for expecting the documentary to end here. But, as Bani Singh asks, “How do you enjoy the Gold and keep the trauma of what happened just before it down?” In the second half, she embarks on a journey to find a phantom figure who kept popping up throughout the story: Shahzada Shahrukh (1926-2015). Shahrukh was an old Government College boy who had been particularly close to Singh and Dutt, even helping the latter escape from Lahore in disguise as communal riots ripped through the city. After losing in the semi-final, he was a spent force, according to Dutt, but would later represent Pakistan in the Olympics in cycling.

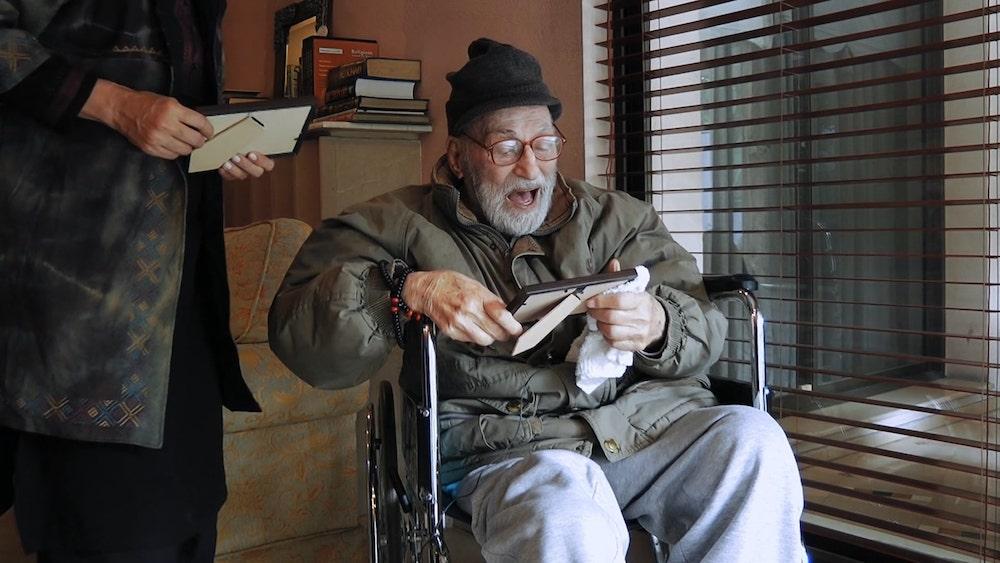

Bani Singh's search takes her across the border, back to the Oval where it had all started for the three friends. After several failed attempts, she finally tracks Shahrukh down. He takes a moment to recognise the photographs that Singh hands him. Clutching the photos tightly, he starts kissing his old friends, tears streaming down his eyes. “I used to love Keshav a lot,” he says. “Keshav also loved me a lot. Who knows what went where. [The] Partition ruined a lot of families.” Curiously, the three friends did not wish to reconnect over a video call (although Singh and Dutt were in touch), as Bani Singh explained after a screening at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival in April this year. There was a silence around the trauma of Partition. “I had not understood this before or the impact of their loss as they never spoke about it,” says Singh.

Shahzada Shahrukh receives photographs of his friends in his Lahore home.

Given the wider appeal that an overt Partition narrative could have, the director deserves credit for resisting the temptation to recast the story in light of her meeting with Shahrukh and their non-reunion. Bani Singh and editor Abhro Banerjee invite the viewer to re-enact their journey through triumph, loss and rediscovery, without making it episodic. Despite the narrative following the historian/story-teller’s route, the film's unity is never compromised as the ending offers a new vantage point from which to view the Olympic story of Grahnandan Singh and his friends. Besides archival videos, photographs and scrapbook material that enrich the research, Singh also incorporates footage of herself revisiting old interviews and connecting with friends, inscribing into the documentary the long and arduous process of its making—the difficult months following her father’s passing and subsequently, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bani Singh listens to a recorded interview with her father.

Taangh has already won the Best Documentary (Feature) at the New York Indian Film Festival besides other recognitions at DokuBaku (Azerbaijan), the International Documentary and Short Film Festival (Kerala), and Kolkata People’s Film Festival (Kolkata), where the audience broke into spontaneous applause at several points during the screening, as if it were a performance unfolding in front of us. It deserves a place among the finest non-fiction works (film and other media) on sports (comparable with C.L.R. James’s Beyond a Boundary or Stevan Riley’s Fire in Babylon), on the Partition and indeed on friendship.

All images from Taangh by Bani Singh. India, 2021. 98 minutes. Images courtesy of the director and Kolkata People's Film Festival.

To read more about the films screened at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival 2022, please click here and here.