Disco Music and the Diaspora: A New Islamicate in Bombay Cinema

In a feature published in the November 1982 edition of Filmfare, the Bangladeshi Muslim playback star Runa Laila was derided for crossing over from the respectability of her hit ghazals “Ranjish Hi Sahi” and “Dumadam Mast Kalandar”—and the “enthralling number” “Tumhe Ho Na Ho” from the film Gharonda (Bhim Sain, 1977)—to the disreputable quarters of disco, as the release of Superuna, a collection of ten songs was announced. The feature mockingly says that Superuna could have been called Discoruna.

Runa Laila featured in the November 1982 edition of Filmfare magazine. Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

In a pre-music video, pre-MTV age, reports of music release parties play a fascinating role in reconstructing the lost visual object. As mentioned in the same Filmfare feature: “…seeing a film of the song picturisations—Runa swingin’ in a disco (“Haiya Hoo”), Runa going bonkers over a guy who phones her daily (“Suno Suno”), Runa plaintively wailing (“Pukaro”) and Runa playing guard for ‘Disco Express.’” Superuna was presented by Bappi Lahiri with a host of lyricists and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) that intended to bring “good international music to India.”

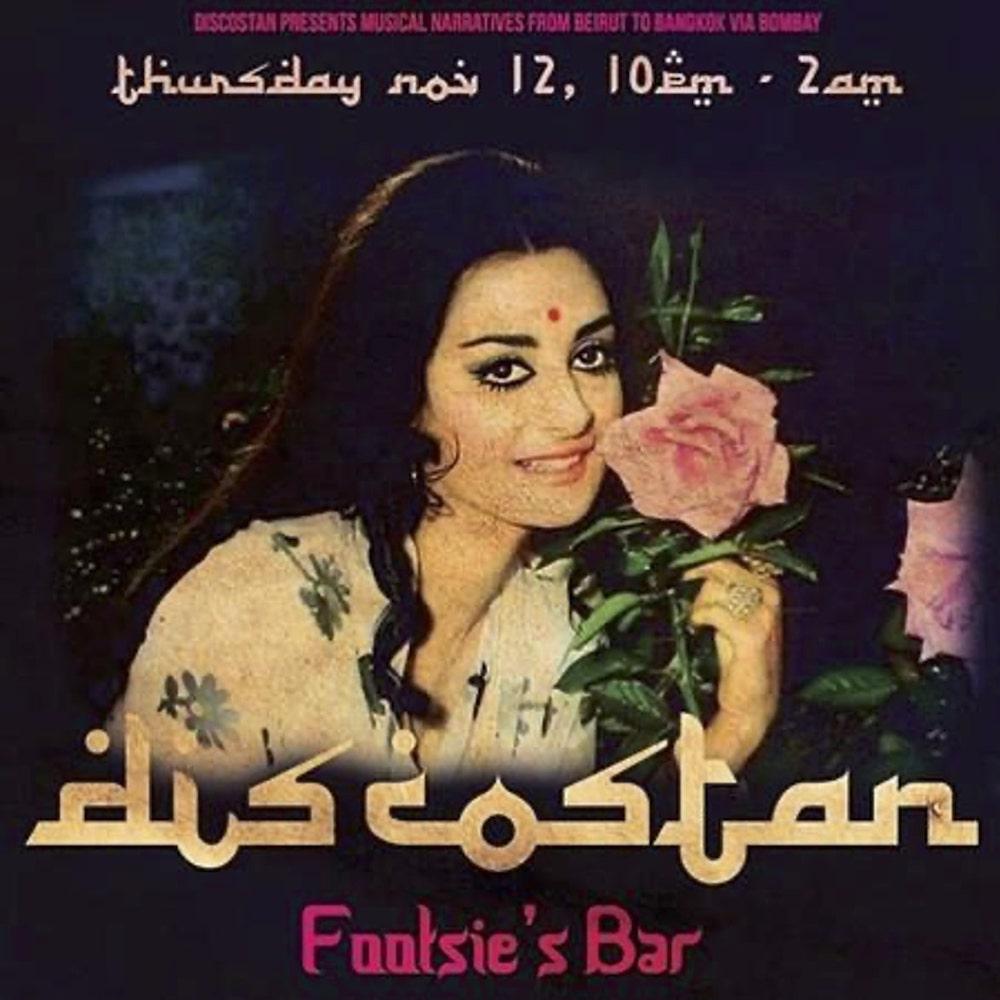

A flyer for Discostan, a record label and collective of diasporic artists and activists based in Los Angeles. Image courtesy of theculturetrip.com.

Arshia Fatima Haq, founder of Discostan, recounts the Superuna cassette beginning with an international invitation: “We welcome all disco lovers on board our flight around the world,” says an air hostess, as the sound of a plane’s engine whirls in the background.” Discostan is a record label and a collective of diasporic Muslim artists and activists based in Los Angeles, connected by their collective affinity for disco sounds from the Global South. Haq also recalls how the album cover features Laila looking like a microphone-wielding superhero in a gold cape. The announcement—along with the album cover and CBS’s Suresh Damle’s intention of internationalising Hindi film music—heralds what I call “a new Islamicate of Bombay cinema in the 1980s,” constituted by diasporic Muslim identities, global travel and exotic locations, and bound together by the rhythms of disco.

In her recent revision of the term “Islamicate,” earlier meant to be the influence of the imagined history, social life and expressive idioms associated with Islamic culture, historian Salma Siddique points out the indeterminacy of the term and redefines it as “the cultural confluence and association of the non-Muslim with the Muslim across time and space.” In 2009, scholars Ira Bhaskar and Richard Allen stated that Islamicate sensibility in India “cannot be reduced simply to the influence of Islam defined in purely religious terms, nor [an] influence reducible to purely Islamic contexts.” Reworking this definition, film historian Anupama Kapse, in 2020, offered the term “Arabesque” to articulate how it feels to “be brown and recognize being brown” within the sensory regime of South Asia and the Middle East. Arabesque thus suggests that the Islamicate is not just a sensibility but a lived experience.

To use the term “Islamicate” to denote an imagined form is no longer tenable in the post-Shaheen Bagh moment. Having witnessed the resilience shown by Muslim protesters, especially women, since December 2019 in the face of state-sponsored and everyday brutalities against Muslims in India, one needs to rethink Islamicate as not merely an aesthetic or imagined form but an ethical project of recognising Muslim presence and solidarities in cinema.

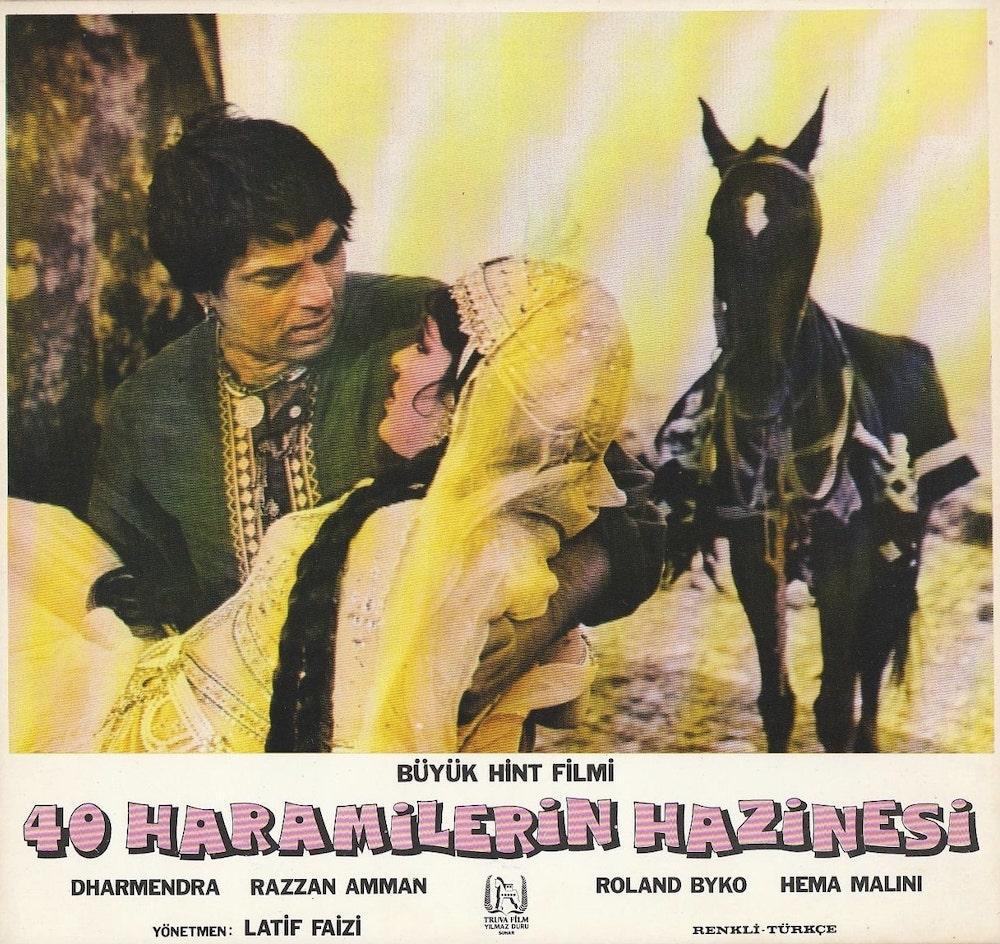

An Uzbeki poster of the film Alibaba Aur 40 Chor, an Indo-USSR co-production released in 1980. Image courtesy of IMDb.

I look back at the 1980s as a radical period of Islamicate in Bombay cinema, driven by transnational Muslim collaborations for film music and a notion of Islamic placemaking within the flux of global travel. This kind of Islamicate collaboration on filmic disco found home in Indo-USSR co-productions. Some of them included Alibaba Aur 40 Chor (Umesh Mehra and Latif Faiziyev, 1980) by Uzbekfilms, as well as in the cinema of brothers Feroz and Sanjay Khan, who introduced the global Islamicate onscreen, beginning with Dharmatma (shot on location in Afghanistan, 1975) and Chandi Sona (shot in Mauritius, 1977) and introduced the London-based, Pakistani sibling duo, Nazia and Zoheb Hassan to Hindi film music.

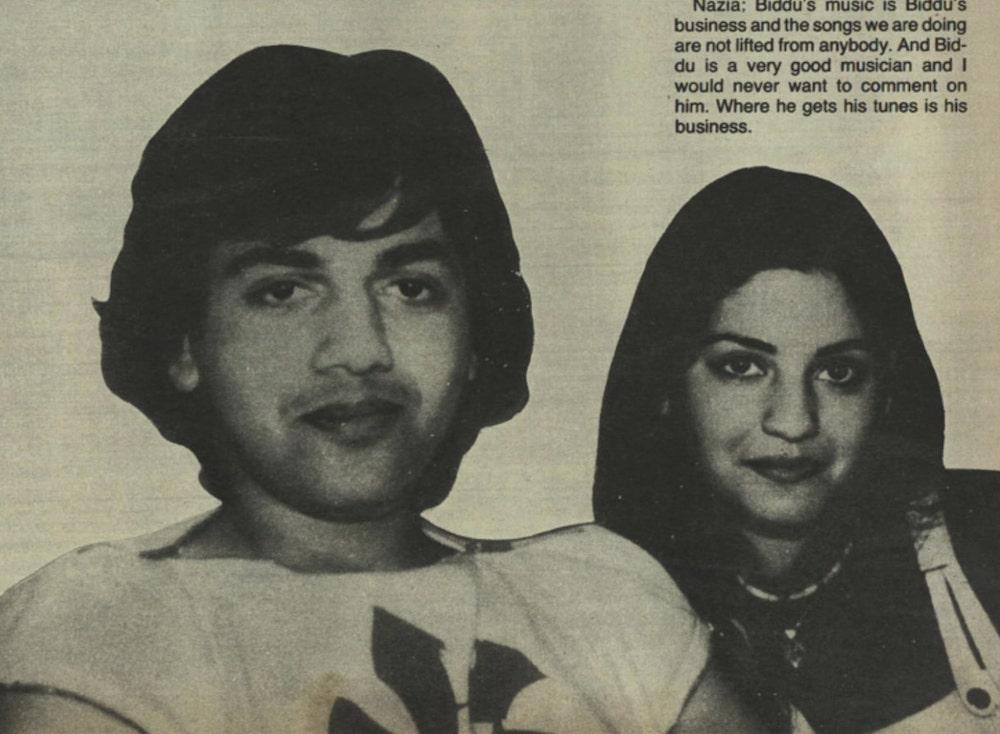

Singers Nazia and Zoheb Hassan featured in the November 1982 edition of Filmfare magazine. The sibling duo shot to fame after the release of their album Disco Deewane in 1982. Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

Nazia Hassan sang the famous “Aap Jaisa Koi,” picturised on Zeenat Aman in Qurbani (Feroz Khan, 1980). Nazia and Zoheb were catapulted to stardom in India with their album Disco Deewane in 1982. In an interview with A.K. Mittal published in the November 1982 edition of Filmfare, they highlight the global appeal of the moment within which Disco Deewane found international acclaim: “In the west now, Indian music is not considered much, but now there is an international kind of music which is very important […] Our record was an international hit. It was the first Indian record to feature in the charts, which hadn’t happened before.”

Musician Parvati Khan featured in the July 1985 edition of Filmfare magazine. Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

Parvati Khan in the studio with film director Babbar Subhash (left) and music composer Bappi Lahiri (right), 1981. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Parvati Khan, another musician from London, was born in Trinidad to Hindu parents but acquired the Islamicate through her upbringings in cosmopolitan cultures and marriage to poet Rahi Masoon Raza’s son, the cinematographer Nadeem Khan. Starting as a ghazal singer, she lent her voice to “Jimmy Jimmy Aaja” in Disco Dancer (Subhash Ghai, 1982) for which she received her first gold disc. Khan went on to sing for several films including Ab Meri Baari, Meri Kahaani, Shart, Andhere Ujale, Maa Kasam, Pratibha and Misaal.

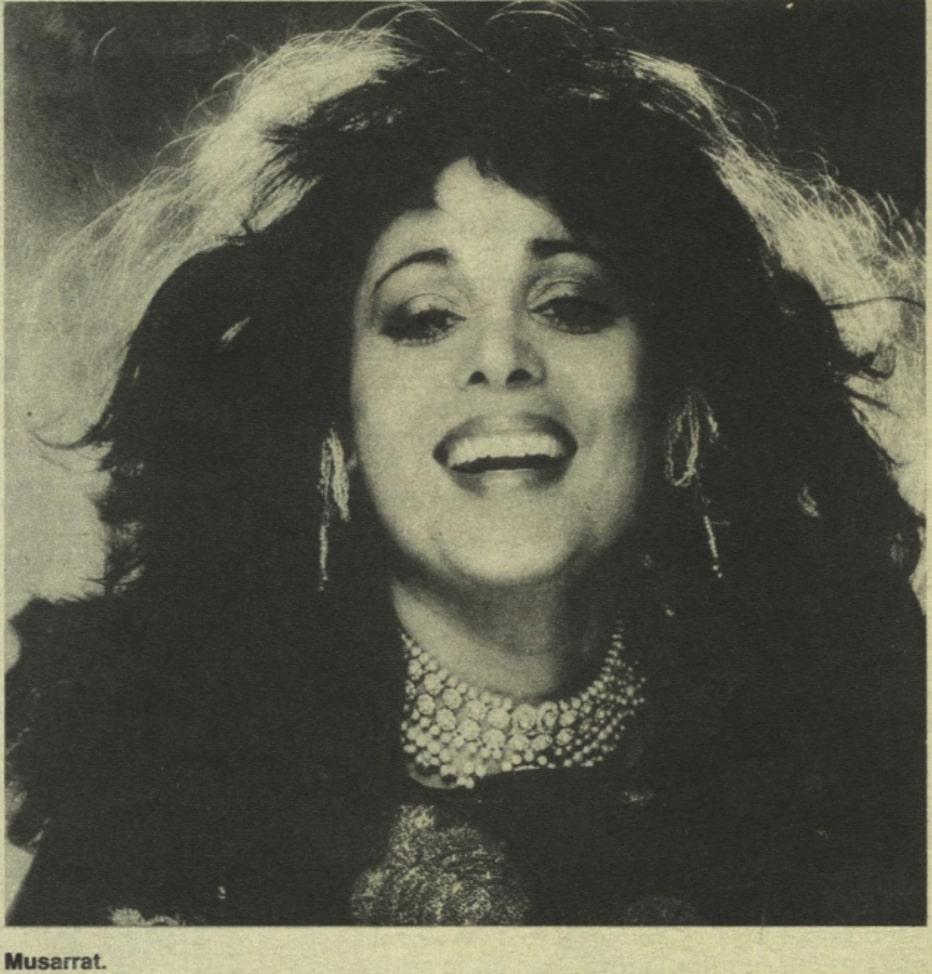

Pakistani-Canadian disco star Mussarat Nazir featured in the May 1981 edition of Filmfare magazine. Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

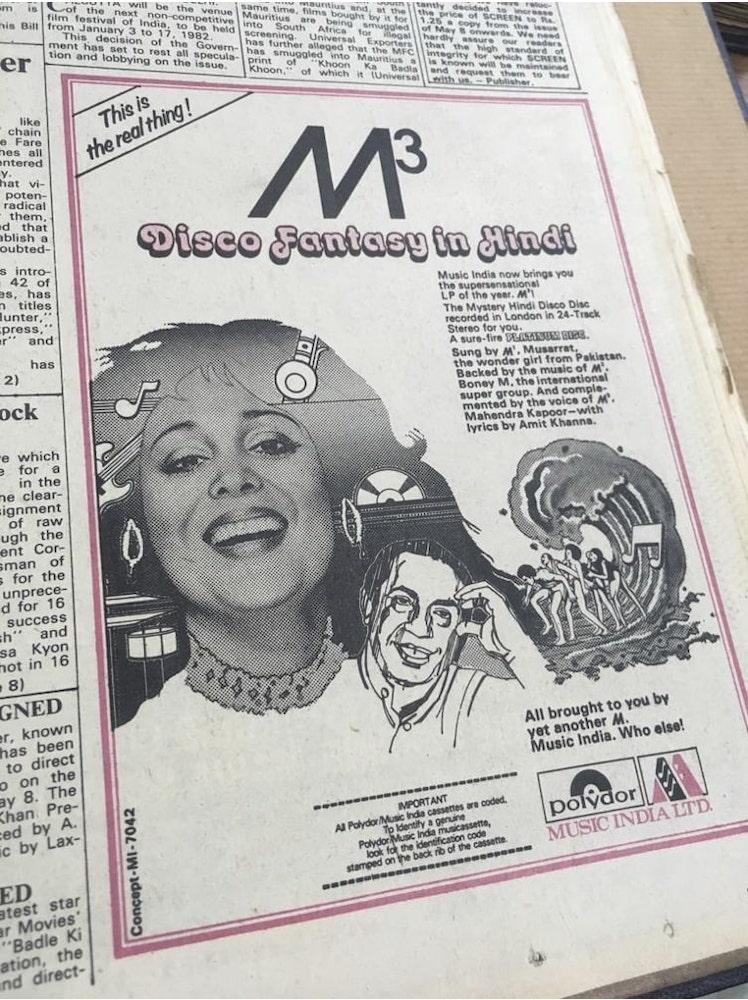

An advertisement of Mussarat Nazir's album M3 in the July 1982 edition of Screen magazine. Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

A third disco star of the moment was Musarrat Nazir, the glamorous Pakistani Canadian known for hobnobbing with former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and wearing only haute couture clothes. Her album M3 (featuring songs sung by her and Mahendra Kapoor to Boney M’s music) found a grand welcome in Bombay. Her electrifying presence on Indian television left many to wonder if she would be seen in movies. In a recent online post, her son Omar Majeed recollected that Musarrat Nazir had been a glamorous film star in Pakistan, a life she had given up on marriage only to find musical stardom in London in the 1980s, singing what he and other second-generation desi children in North America found disreputable covers of international disco labels.

To read more about the disco revolution in Hindi film music, please click here.