Naked Repose: Undoing the Street in PHOTOINK’s The Passerby

Possibly one of the most immediate areas documented by the camera, the street remains a fast-paced, ever-changing milieu for photographers who are drawn to its textured expanse. The street as a genre holds multitudes, allowing image-makers to pursue a variety of interpretations, evident in works produced across decades, continents, technological developments and modes of display. It persists as a canvas populated by the expressiveness of the ordinary.

Displayed at Photoink, The Passerby brings together a selection of twenty-three black-and-white photographs by Ketaki Sheth, Pablo Bartholomew, Raghu Rai and Sooni Taraporevala, stitching together a view of the street as encountered through decades of their photographic practice in India. The exhibition posits their individualistic perspectives in a manner that allows one to ask: What is the street—how is it shaped, and most importantly, where is its locus? Transcending self-evident answers to these questions, The Passerby extends an invitation to the viewers to revel in the glimpses and imaginations of these four photographers through their perceptions of the street—each image a reminder of the kinds of negotiations that underline any act of photography. One is made aware of how the subjects possibly came to be, and we are urged to consider the necessary performativity at the heart of the act, cutting through the comfort of genre-categories and the ever-prevailing spectra of the truth-value of photography.

Two men, (Raghu Rai, Old Delhi, 1970. Image courtesy of Raghu Rai and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Raghu Rai

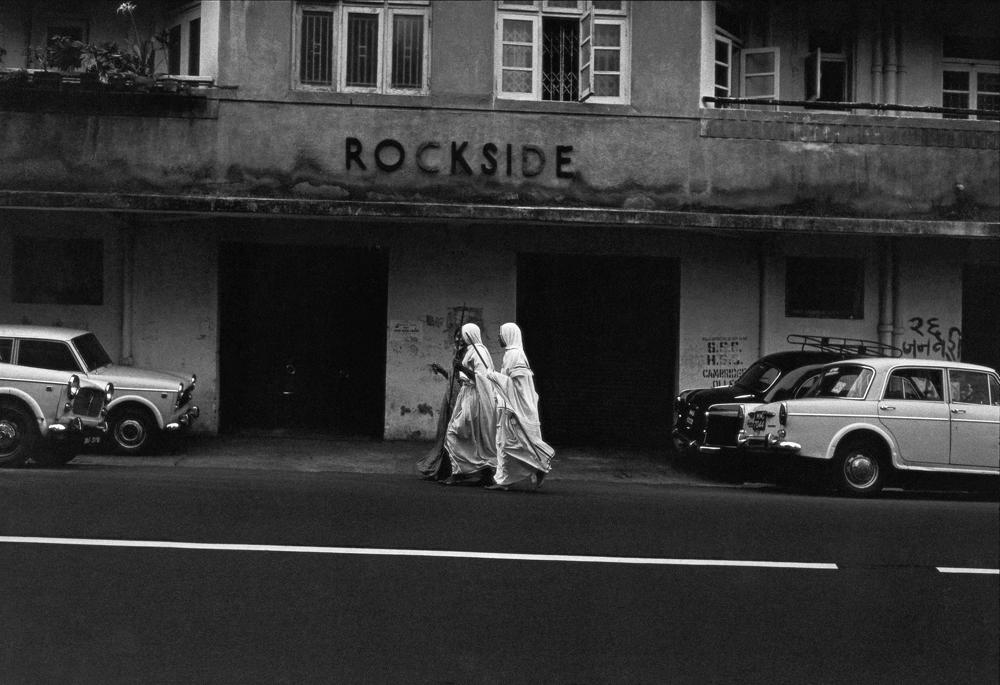

Jain nuns (Ketaki Sheth, Walkeshwar Road, Bombay, 1989. Image courtesy of Ketaki Sheth and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Ketaki Sheth

As an exhibition on street photography, The Passerby retains delicious citation, with each photograph titled after what is included in them. The photographs illuminate the sheer unbridled fluidity of movement, distilled as an essence. Motion is silhouetted against the stillness of the photographic image, and both the photographer and the photographed seem to be passing by each other while seeing and being seen by the other. The display presents the images in multiple clusters, subtle in their intonation of themes, leaving much to be interpreted by the careful viewer. In the commonalities that arise among the clustered images, the street is distinctly mapped by artistic vision and the possibilities of the lens, at times predictable in what it elicits from those who seek to remember it for posterity, for those who respond to its stimuli.

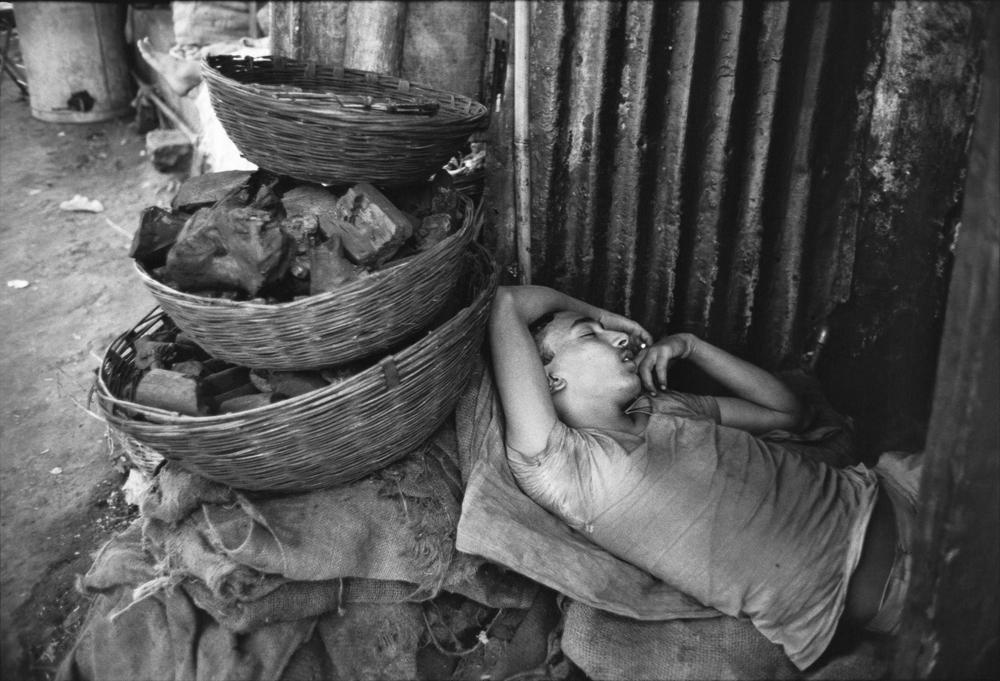

Sleeping boy on the road to Mahalaxmi (Ketaki Sheth, Bombay, 1990. Image courtesy of Ketaki Sheth and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Ketaki Sheth

Siesta for taxi drivers (Raghu Rai, Kolkata, 1990. Image courtesy of Raghu Rai and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Raghu Rai

The first cluster one encounters is a set of works by Raghu Rai, Pablo Bartholomew and Ketaki Sheth that frame the primordial act of walking, where the street as a site of traversing emerges as a bare-bones landscape. An added layer to this set is the causality of the street taking shape through the form, direction and purpose of the foregrounded bodies that intersect mid-stride across each frame. In another cluster with more works by Bartholomew and Rai, the street anchors the laboring body—carrying, bearing and burying—dictated by the burden that distinguishes it. In a different gathering of images, rest permeates the visual, and there is a conversation that emerges across three images by Rai, Sheth and Bartholomew, one of equivalences being formed between the viewer and the viewed. Rest is programmed into any reading of how the street appears, where it is shelter for some, threat to others, or is carrying the imminence of absence and of feeling bereft. All of which returns us to the question of locus—in every act of locating the street, what are its affordances allowed to us?

Women of Kamathipura (Sooni Taraporevala, Bombay, 1987. Image courtesy of Sooni Taraporevala and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Sooni Taraporevala

Eunuchs strike a pose (Pablo Bartholomew, Grant Road, Bombay, c. 1976. Image courtesy of Pablo Bartholomew and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Pablo Bartholomew

In reading the breadth of the oeuvre amassed by Walker Evans, for instance, one is amazed at the omnipresence of portraiture as a key tradition of grasping the street through photography. The visual catalogue of modern America, as created by Evans finds its roots in the vernacular face, the common person, the mundane countenance. In The Passerby, we witness the portrait removed from a certain sense of sanctimoniousness and descending into the wayward architecture of the street, blurring disciplinary and narrative lines in very broad strides. Rai’s photograph of a boy laughing as he flees records a spillage of time and boundlessness; Sheth captures the abandon of yet another as he skips over a puddle. In his wake, the street takes shape as a cartography of the fragments of several cityscapes pieced together. Sheth’s compositions extend beyond the edges, they are often tilted and they bloom, making her vision of the street an angular experience. Taraporevala’s image of a boy watching a film shoot in Bombay while balanced on a bicycle seat brings to the table a cinematic stillness accompanied by an expansive threshold-in-waiting—a liminality of genre that extends the her subjective composure onto his environment. Her photograph of the women of Kamathipura parallels watchfulness with the pensive. Nothing is audacious here but the composition of the image, much like sexuality itself, is a spectrum of reclamation in the street.

Laughing boy (Raghu Rai, Old Delhi, 1975. Image courtesy of Raghu Rai and PHOTOINK) Copyright: Raghu Rai

Boy skipping over puddle (Ketaki Sheth, Ganesh gully, Lalbaug, Mumbai, 2004. Image courtesy of Ketaki Sheth and PHOTOINK). Copyright: Ketaki Sheth

With street photography, the act of passing by is cemented as something to be considered and elongated beyond the misery of its transience. The street is not revolutionary outside of its activation through the presence of those who wish to stay until they are heard. To heap civic pride onto the street as an object or a collection of objects limits the ways in which it can be read: invitingly conversational, a gathering of difference and verisimilitude, and most poetically as a pause between monuments and monumentality.

Note: The title is a reference to a remark by Walker Evans, talking about his series of portraits in the New York City subway. “The guard is down and the mask is off,” he remarked. “Even more than in lone bedrooms (where there are mirrors), people’s faces are in naked repose down in the subway.”