Three Poems

Found Poem: Verditer Flycatcher

The green rust of copper, says Ali.

And a black patch

in front of the eyes. The soil

squeezes out a rainy May. Kausani

on my birthday. There was dizziness

the gift of breath, an imminent coming

everywhere. You will find it, says Ali, in the forested

hillsides, well-wooded gardens, electric wires.

Why am I here? In the limbo

of pages, a stranger’s gasp of recognition, gutter-

space between plates, reeling

incoherently, settling a species

of my mountain familiar. This flycatcher.

My lens is too small to catch its exposed twig perching.

It launches agile sallies after

winged insects, says Ali.

But my shifting hands

tremble so. The eyehole

cracks open. I, too, am perched

exposed on a slippery path

holding my camera like a non-believer’s prayers.

It is a bold and confiding

little creature, says Ali.

Indian Hill Birds

(i) On Size

How do you measure

a bird in the wild? The eye scans

a rumour from the beak

to the end-tip. What about the wing

span? Will the ruler measure

a tail that is kite-ribbon, or current

of restless fish? Sometimes the tape

is not enough and the calliper

too sharp. It tightens

around the body. The standards

refer to all that’s common. The sparrow

is six inches; the vulture

thirty-six. And in between

bulbul, mynah, pigeon,

crow. The key crawls

back to them. A beastly

almanac that says palm-sized, arm-sized,

horn-sized, strut-sized, love-sized. The book

cannot claim this. The birds

are only page-sized.

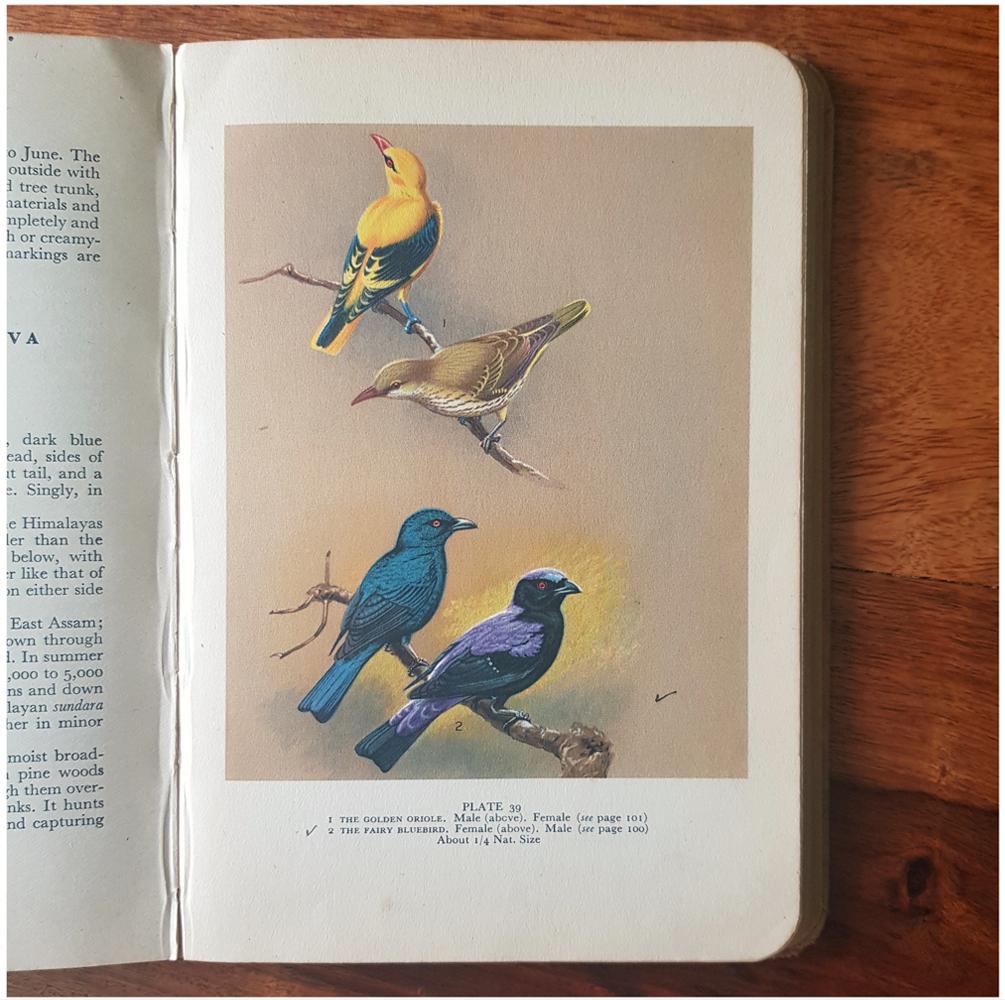

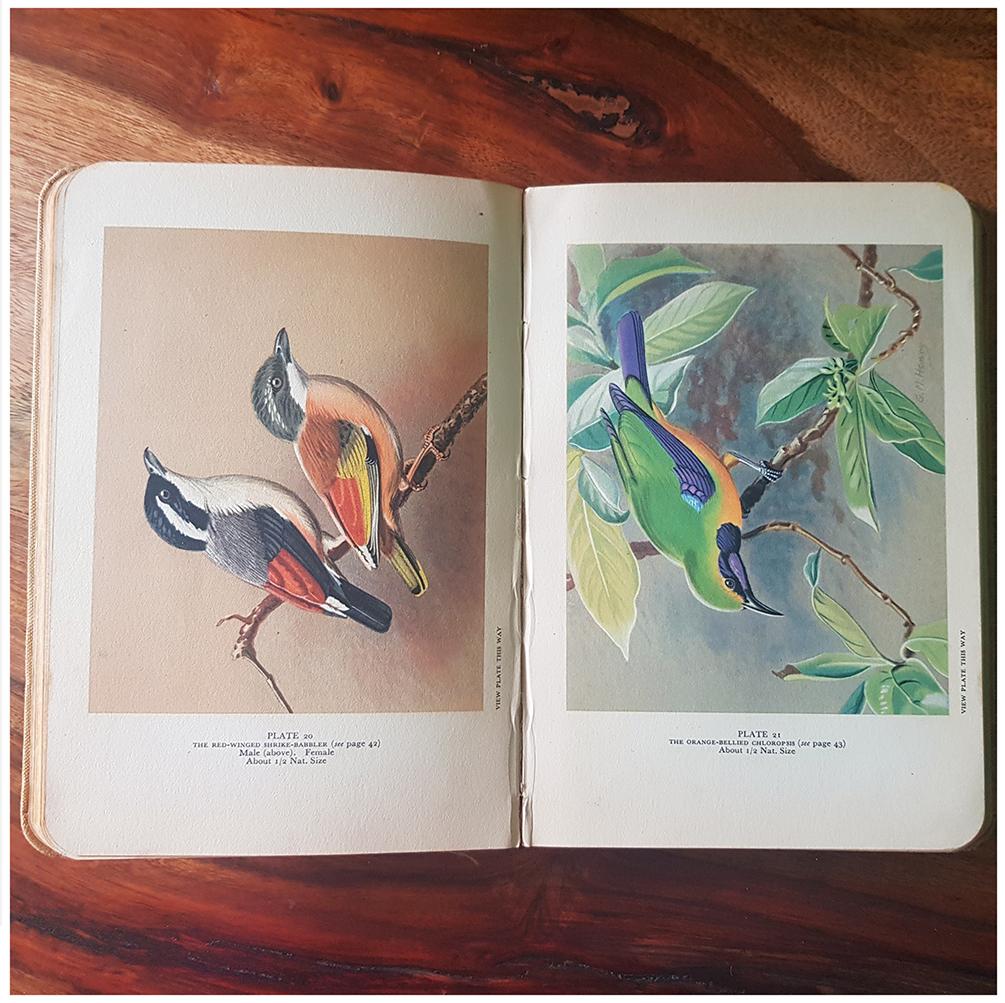

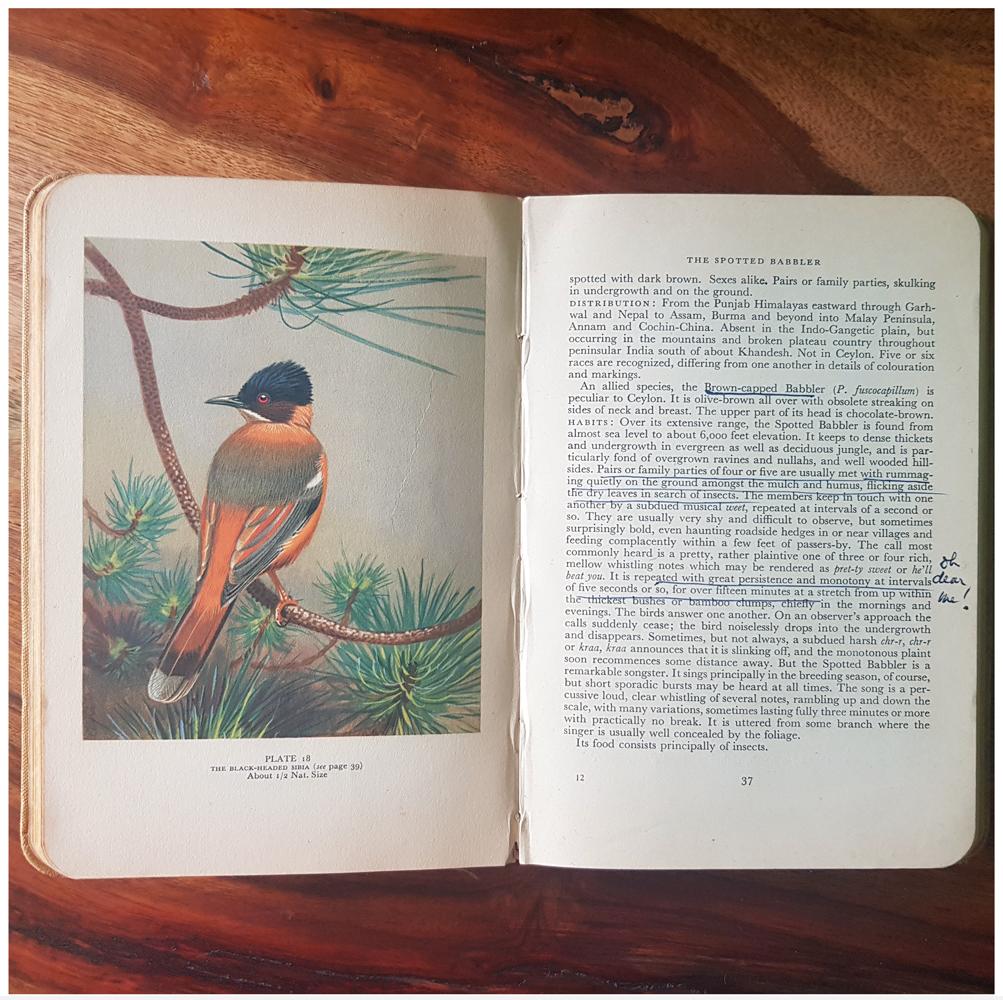

(ii) On Colour

For G.M. Henry, Illustrator

I can’t name the birds now.

They don’t exist

with their ancient names. Their painted

shapes surge out of the pages

in pre-pixel innocence and sing

near the lantana, on swinging

creepers, from mountain tops

unaware they are no longer

what they used to be.

Indian Blue Chat, Kashmir

Red-flanked Bush Robin, Blue-headed

Rock-thrush: unrecognisable in language

ciphered in colour instead.

The blues of a narrow incision

in memory, a never-ending indigo that lives

like a lightheaded note in the city, the hollow

yellow of a sideways, flickering

geometry, orange of a fickle

wingtip. And in all

bokeh of a large flatbrush

mixing browns and greens

of a hunger, distracted

and chaste.

(iii) On Identification

Any discovery

is a nightlong lament.

A poring over of field guides, seeing

the organism burnt

on paper, the calls rendered

like magic (phwee-

phwee-phwee).

Here’s the rictal spot, there’s the purple

rump; here’s the conspicuous

supercilium, there’s the flare

of a vermilion fan. What will this alertness

tear into flesh? An expansion

of lichen and fern

roots, aerial and majestic

ever-ready clouds

will usurp all mind, all body.

And I will run headlong

into the words like a bird

secretly hopping in the undergrowth

keeping the bonewhite

of its feathers hidden.

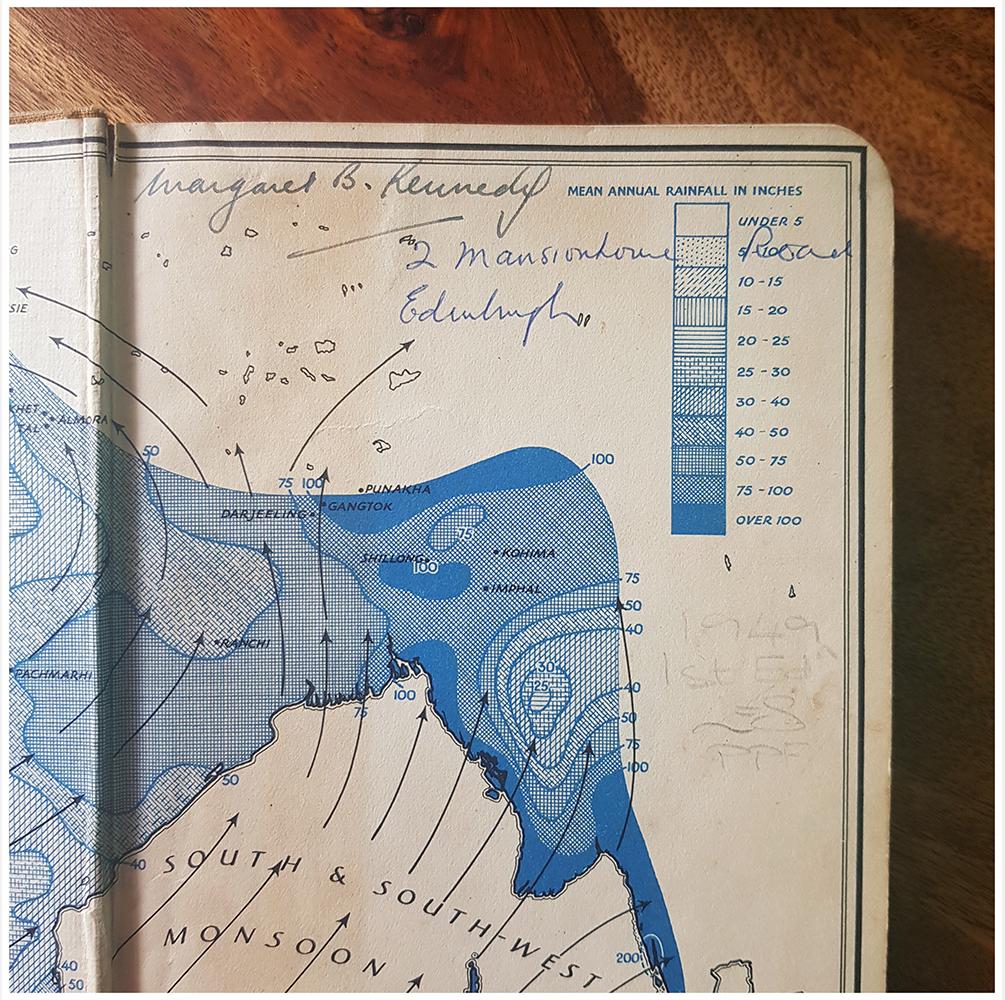

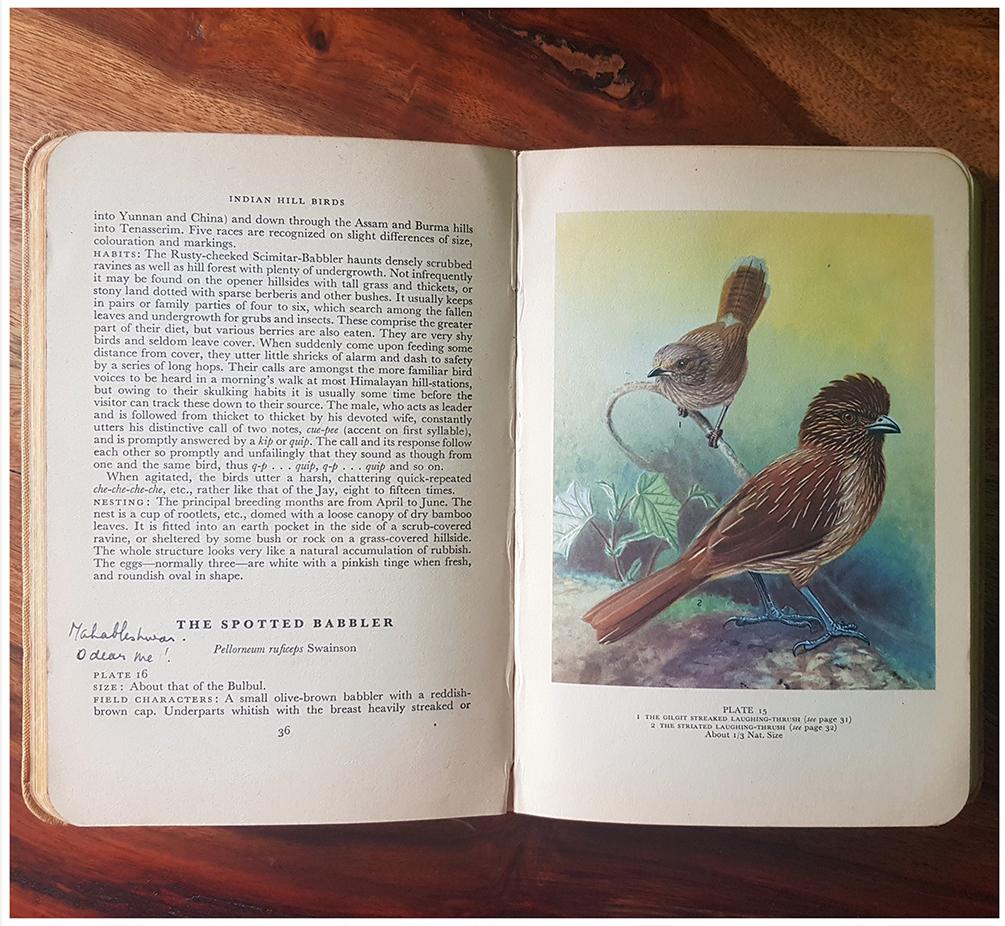

Margaret’s Marginalia

“Oh dear me!” writes Margaret

when either the bird or the prose

that props it gets too much for her. It is repeated

with great persistence and monotony at intervals of five seconds or so…

the call of the babbler either pret-ty sweet or he’ll beat you

and Margaret can only underline quickly, her lines jagged

for once, and write O dear me!

Her ink loops through the pages

now blueblack, now faint

cursive strokes of prim ticks and travels. I saw

this/I saw that. Each bird seen

stained with a shy mark. Is she dead now? Was she twenty

in 1950? A coloniser’s daughter? And was she shy?

Perhaps not. Perhaps scribbling Darjeeling, Pachmarhi

Mahableshwar could balance the map. The periphery

of the book is burdened by crosses

and exclamations. Loss

in the parenthetical “heard only”

or rupture of “en route” when you are not ready

for a sighting, but there is the grace

and miracle of an appearance.

A hurried celebration of wings, a straining

song, a confusion in the bushes

when you least expect it. And an exhaustion

in the swift list on endpaper.

The birds have different names now

dated like pen and ink notes

condemned to the frailty of pages, windblown

travel-weary, blotted by water.