Film as Art (Objects): Notes on Project Cinema City

In an interview with scholars Bhaskar Sarkar and Nicole Wolf, published in the journal Bioscope in 2012, filmmaker and curator of the eponymous Project Cinema City Madhusree Dutta discussed the need for collaborative practice in the making of such a grand initiative:

“In order to take account of the multiple locations, channels, economies, creative practices and imaginaries through which Bombay/Mumbai and the city’s cinema negotiate and constantly re/produce each other, we needed multidisciplinary forms of research and similarly, diverse approaches to documenting, archiving, and ultimately disseminating.”

The series of exhibitions that emerged from the project involved such a coming together of film practitioners, contemporary artists, architects, theorists, scholars, designers and institutions working distinctly and collaboratively to create a visual experience that was simultaneously creative, archival and pedagogical. Renowned individuals such as Pushpamala N., Paromita Vohra, Atul Dodiya, Shreyas Karle, Rohan Shivkumar, Kaushik Bhaumik, and pan-Indian institutions like Doordarshan, Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT), Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), Shreemati Nathibai Damodar Thackersey (SNDT) Women’s University, and Max Mueller Bhavan among others, became auteurs in this multidisciplinary laboratory, each offering a set of questions and concepts within the curatorial framework.

Of the several ideas proposed by Project Cinema City, many were concerned with the place of the still image within the visual culture of cinema. Kausik Mukhopadhyay’s interactive installation Bioscope, for instance, made with Amruta Sakalkar, was a direct nod to one of the earliest devices of cinema—literally a mobile box of images that would travel from neighbourhood to neighbourhood for entertainment. Traditionally, the experience of the bioscope did not rely on narrative continuity, as Dutta mentions in the exhibition text. Unlike formal modes of film screening, the bioscope was an assemblage of lenses and strips of celluloid, and its ability to travel, to exist in multiple forms, was its primary purpose. Mukhopadhyay and Sakalkar’s iteration, Dutta avers, stays away from a nostalgic reading of the device, focusing instead on documenting its nomadic, improvisatory nature.

Bioscope: Cinema-City-Modernity, an interactive game. (Kausik Mukhopadhyay with Amruta Sakalkar. 2009. Image courtesy of Project Cinema City.)

Installation View of Bioscope: Cinema-City-Modernity, an interactive game by Kausik Mukhopadhyay with Amruta Sakalkar at the Kala Ghoda Art Festival, Mumbai, 2014. (Image courtesy of Project Cinema City.)

“Inside the bioscope snippets of information, gossip, lore and tales about the city of Bombay, its cinema and its engagement with modernity swivel around the circular motion of cityscape and images of matinee idols,” writes Dutta. These images and texts form a game, forcing spectators to become active participants in the understanding of the work. Bioscope simultaneously interrogated the material and experiential aspects of cinema, and, interestingly, the idea of the digital. Cyberspace, with its infinite possibilities and circulation of images, is imagined as a sort of mammoth bioscope in the contemporary world. The past finds itself articulated in the present, creating critical links across time and space.

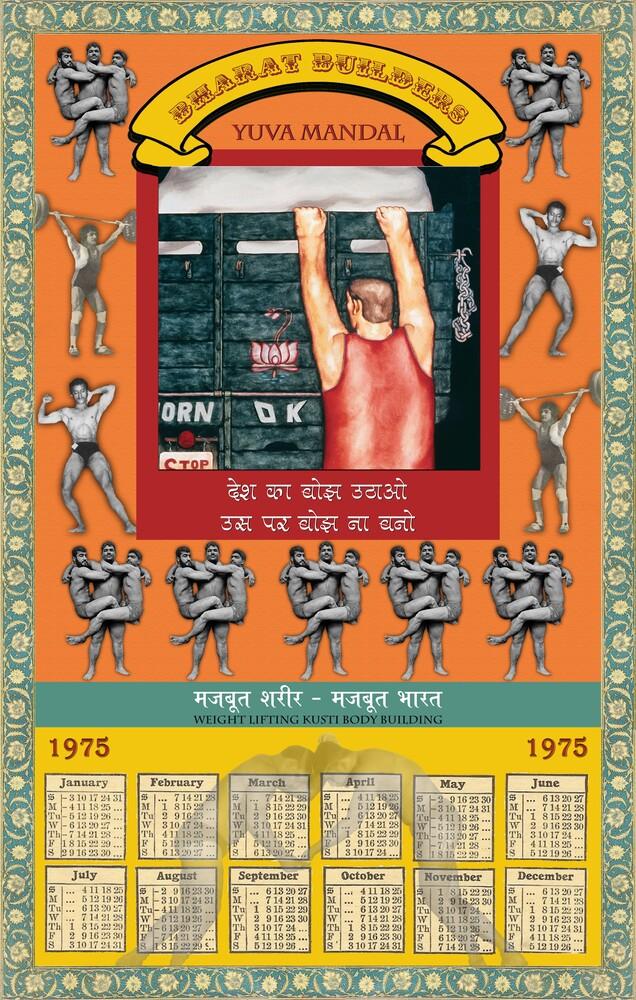

Another work that contemplated the extended visual culture of cinema was The Calendar Project: Iconography in the 20th Century, featuring multiple artists including Nalini Malani, Tushar Joag, Ranbir Kaleka, Ram Rahman and Mithu Sen among others. They reimagined date calendars of the twentieth-century, reproducing them digitally in an attempt to speculate collectively on reproduction in print culture and its relationship with cinema. The works relied on both found and constructed images, featuring film memorabilia, stills, popular iconography and the artists’ own works.

Installation View of The Calendar Project: Iconography in the 20th Century at the NGMA, Mumbai, 2012. (Multiple artists. 2009-12. Image courtesy of Project Cinema City.)

According to the exhibition catalogue:

“The new works, made with the aid of contemporary technology and discourses and yet pretending to be copy of something that never materially existed but recognized by the collective consciousness as old and archival, create a deliberate dent into the practice of turning the reproducible / copy-able street culture into ‘valuable’ assets.”

Installation View of The Calendar Project: Iconography in the 20th Century at the Berlinale Forum Expanded, 2010. ( Multiple artists. 2009-12. Image courtesy of Project Cinema City.)

Youth Power, 1975 as part of The Calendar Project: Iconography in the 20th Century. (Sudhir Patwardhan. 2009-12. Image courtesy of Project Cinema City.)

Project Cinema City makes it clear that in order to create an archive of cinema, or to document it comprehensively, one must go beyond simply preservation of celluloid. Cinema is an experiential entity, one that represents and wrestles with the contemporary. To understand it, it is imperative to examine closely the expansive networks of work, people and images that invest in it and in whom it is ingrained.

To learn more about Project Cinema City, please search for "Archiving Film: Notes on Project Cinema City."